Police Files

MOUNTAIN MAN

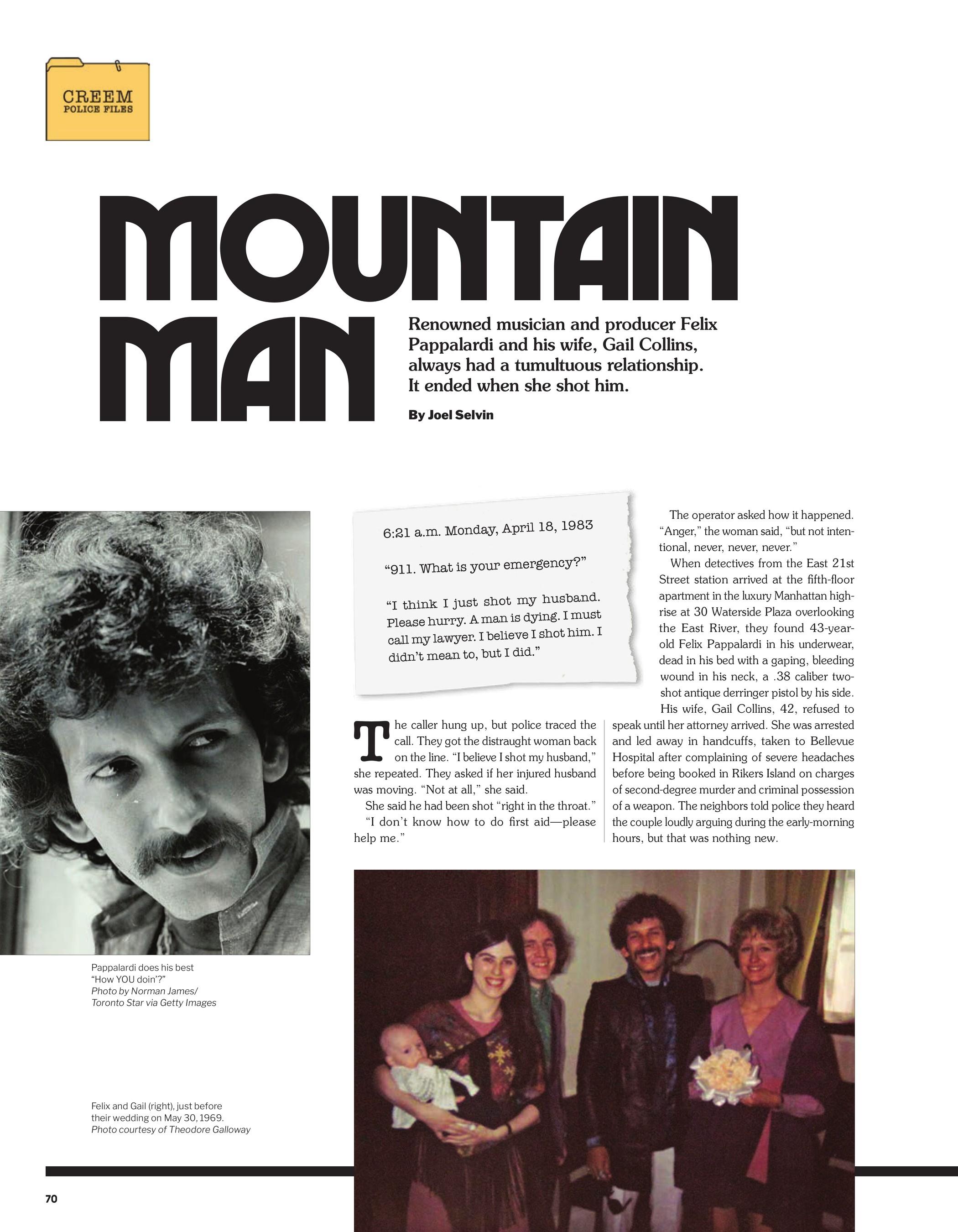

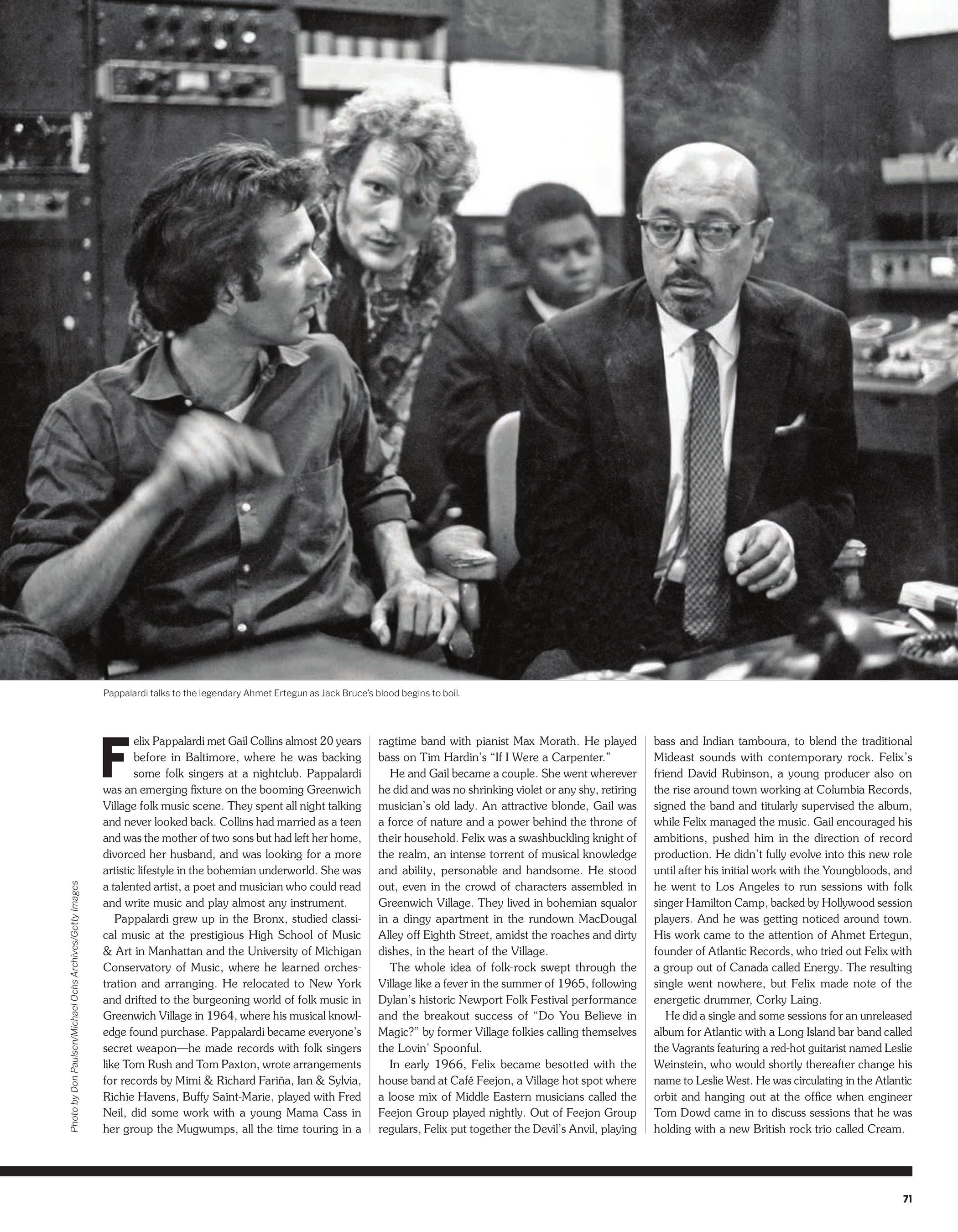

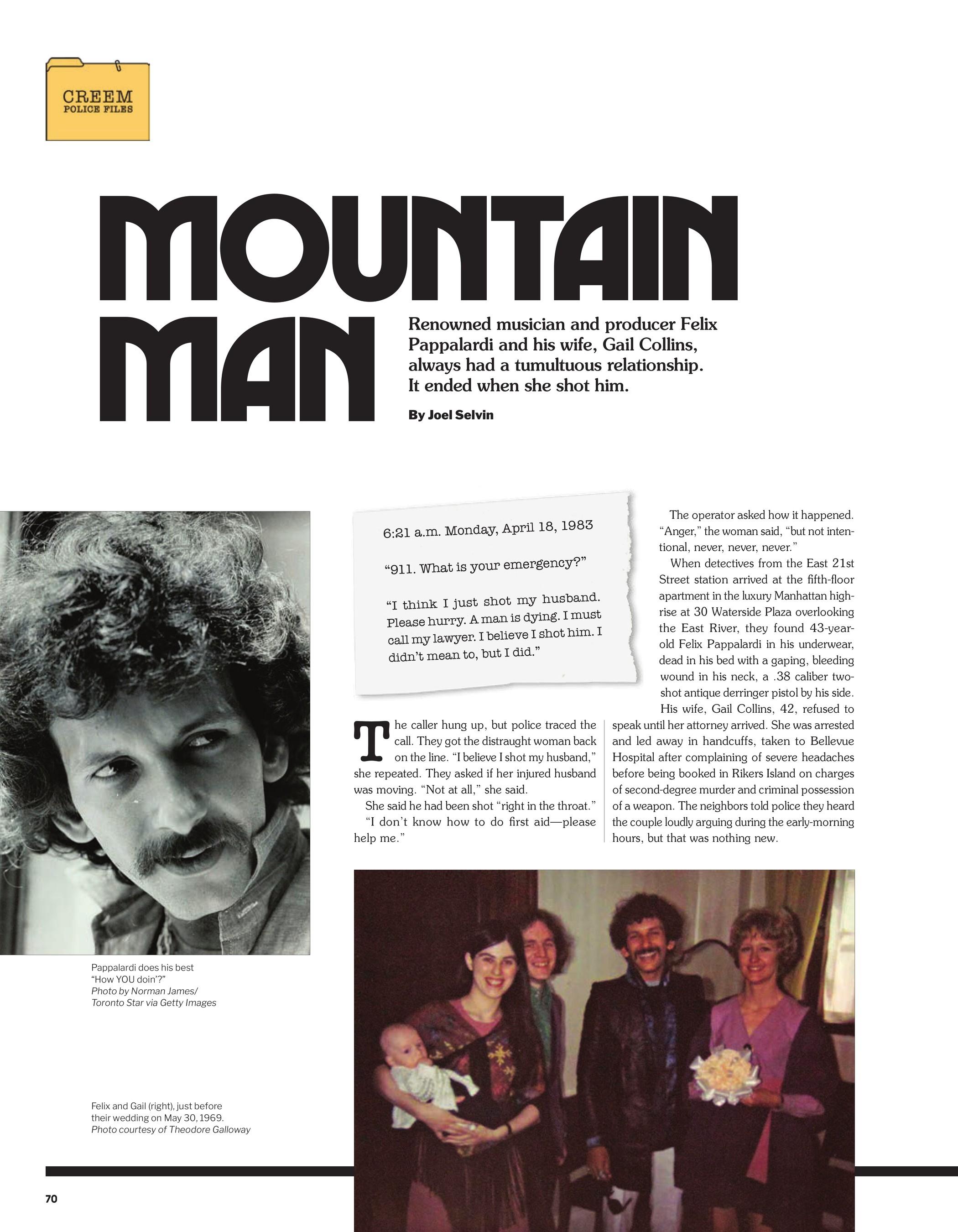

Renowned musician and producer Felix Pappalardi and his wife, Gail Collins, always had a tumultuous relationship. It ended when she shot him.

December 1, 2024

Loading...

Renowned musician and producer Felix Pappalardi and his wife, Gail Collins, always had a tumultuous relationship. It ended when she shot him.

Loading...