The Big Interview

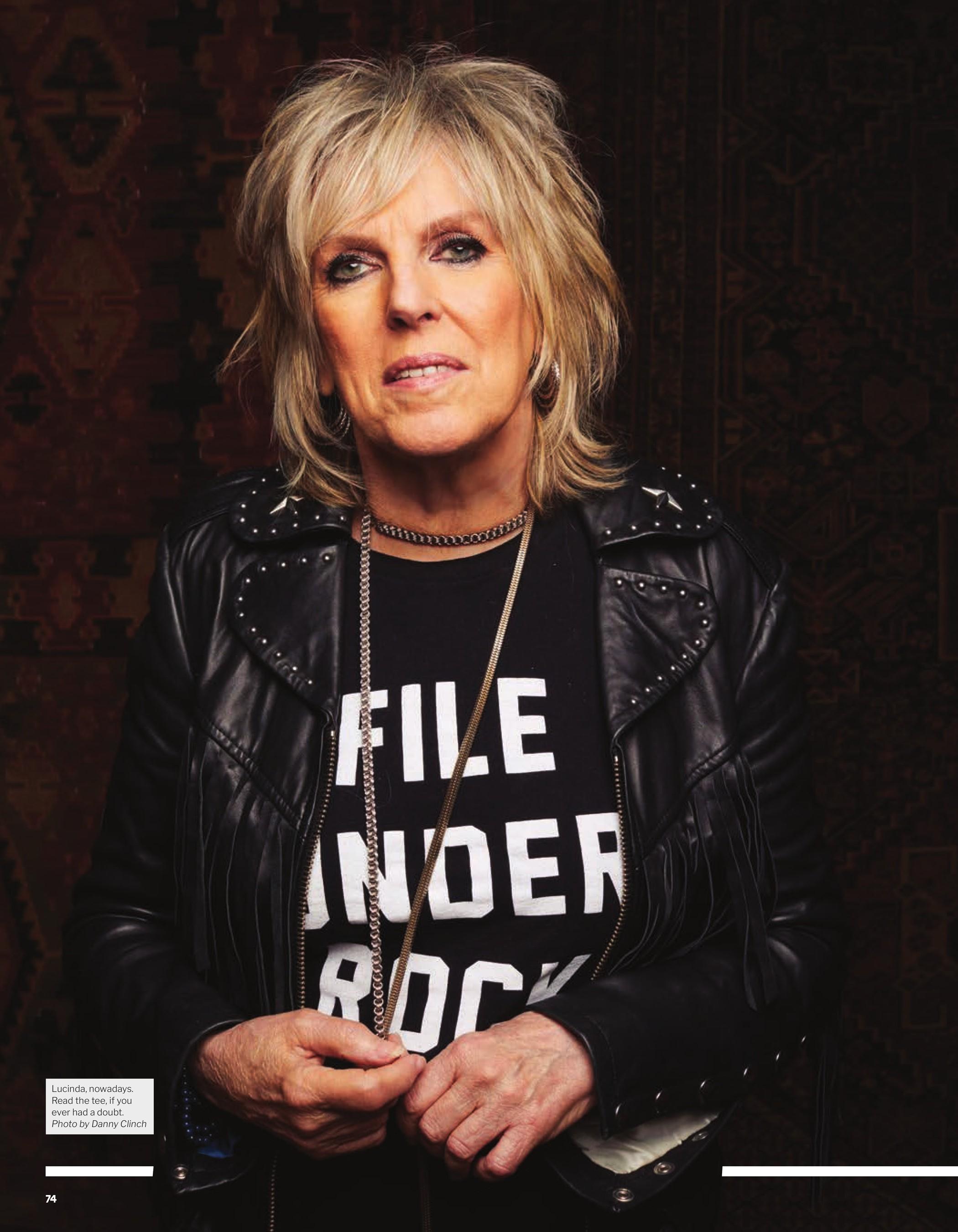

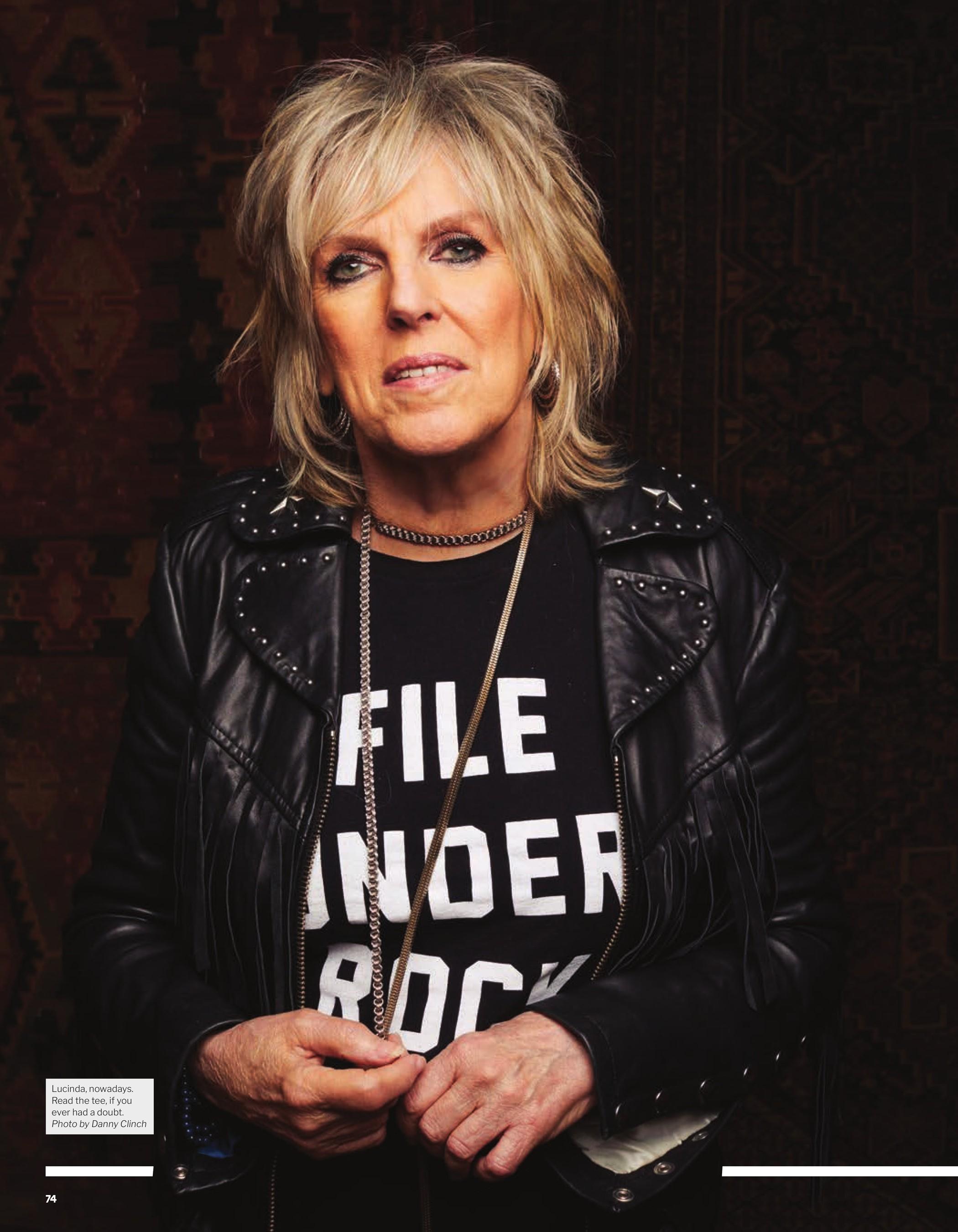

LUCINDA WILLIAMS’ BIG INTERVIEW (NEVER MIND SHE'S ONLY 5'5")

On surviving a stroke, collaborating with her soulmate, and missing Tom Petty

September 1, 2024

Loading...

On surviving a stroke, collaborating with her soulmate, and missing Tom Petty

Loading...