Dusty Fingers

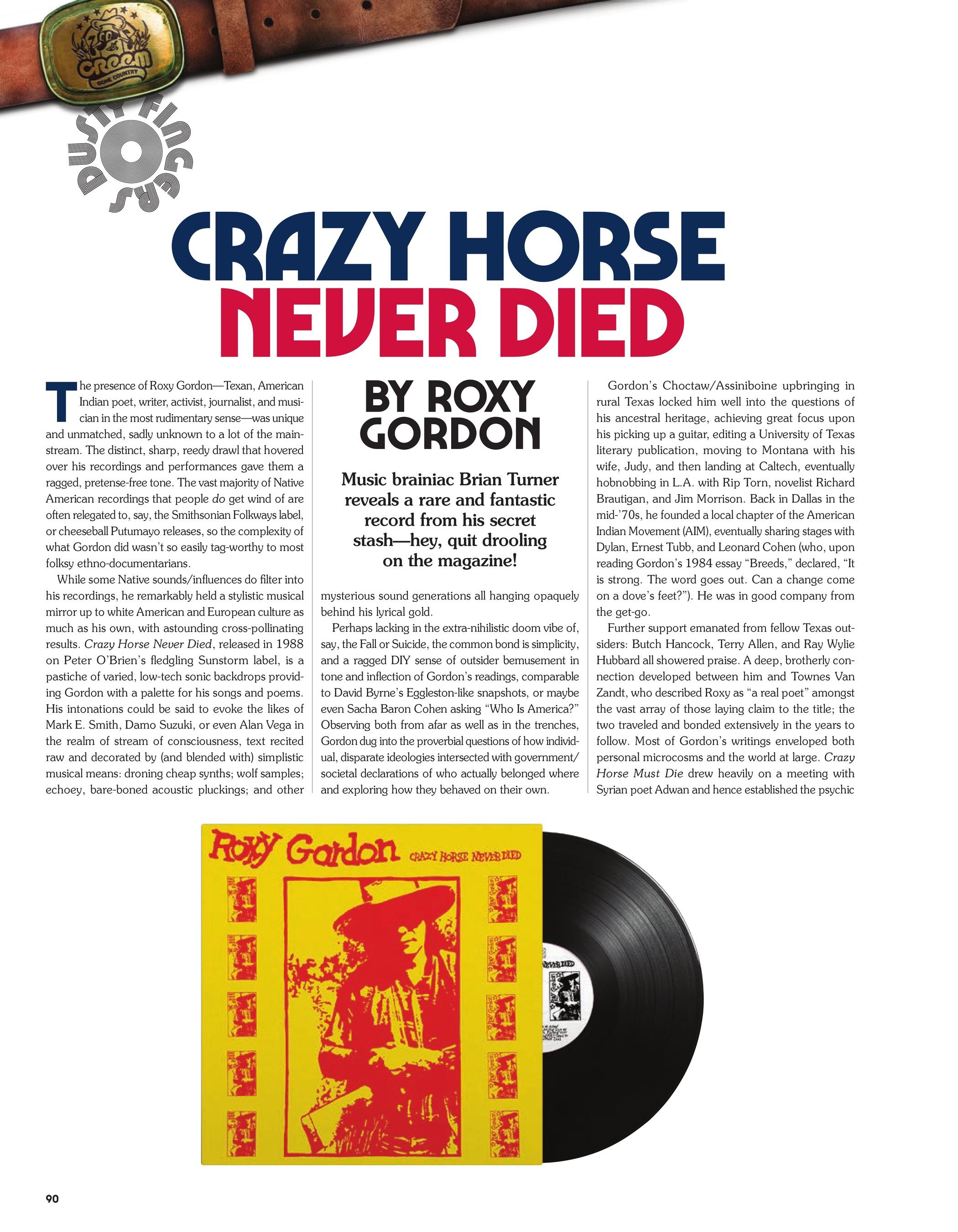

CRAZY HORSE NEVER DIED

Music brainiac Brian Turner reveals a rare and fantastic record from his secret stash—hey, quit drooling on the magazine!

September 1, 2024

Loading...

Music brainiac Brian Turner reveals a rare and fantastic record from his secret stash—hey, quit drooling on the magazine!

Loading...