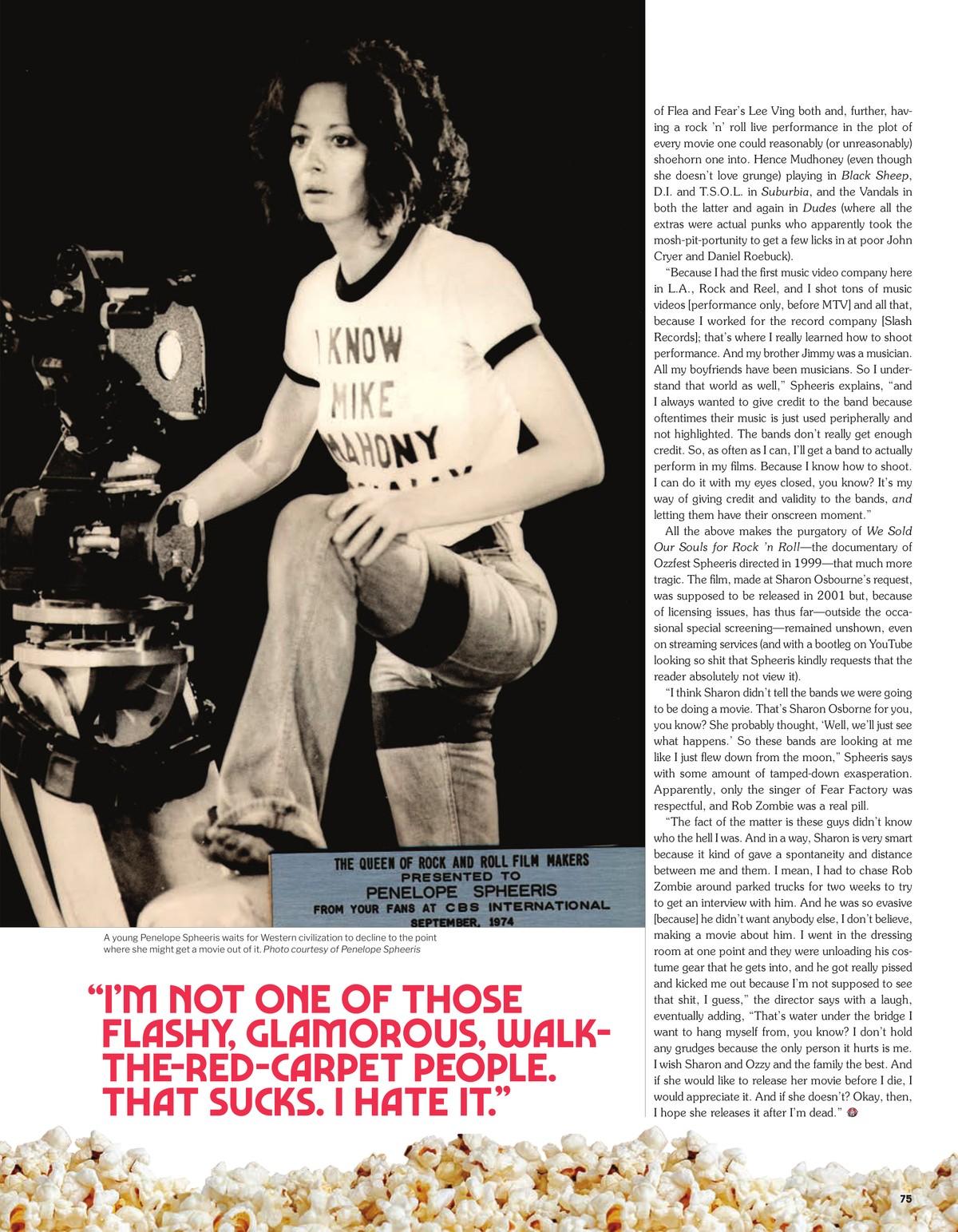

THE PASSION (S) OF PENELOPE SPHEERIS

"I’m not one of those flashy, glamorous, walk-the-red-carpet people. That sucks. I hate it,” Penelope Spheeris says over the phone, the slight rasp of her voice closer to that of a sardonically peeved twentysomething podcaster than someone who was at the ground floor for punk, hardcore, and hair metal, and who covered all three so incisively and authoritatively that all the subcultures of the three that came after were at least indirectly shaped by the templates she was the first (and best) to set on celluloid.

June 1, 2024

Loading...