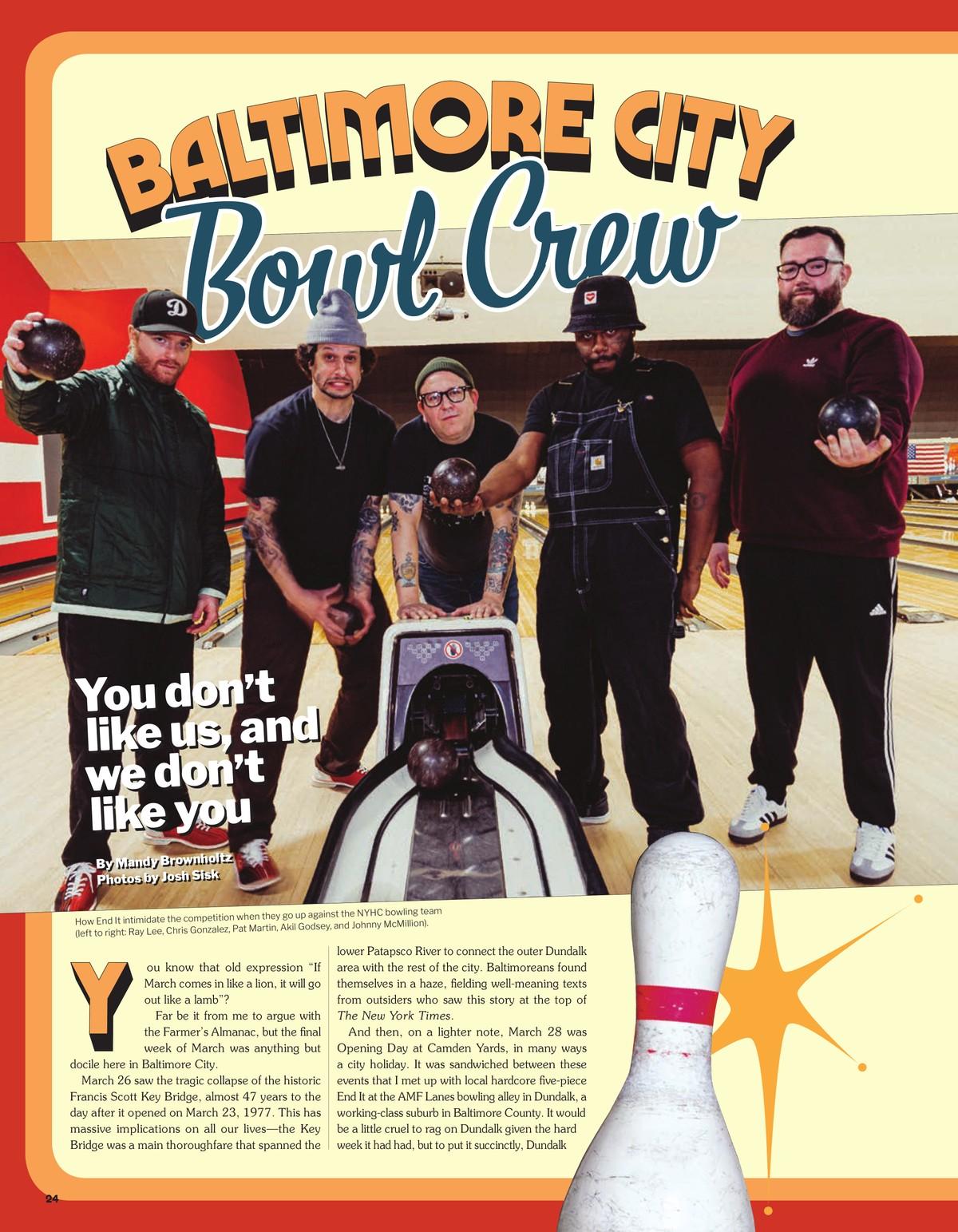

BALTIMORE CITY Bowl Crew

You know that old expression “If March comes in like a lion, it will go out like a lamb"? Far be it from me to argue with the Farmer’s Almanac, but the final week of March was anything but docile here in Baltimore City. March 26 saw the tragic collapse of the historic Francis Scott Key Bridge, almost 47 years to the day after it opened on March 23, 1977.

June 1, 2024

Loading...