Features

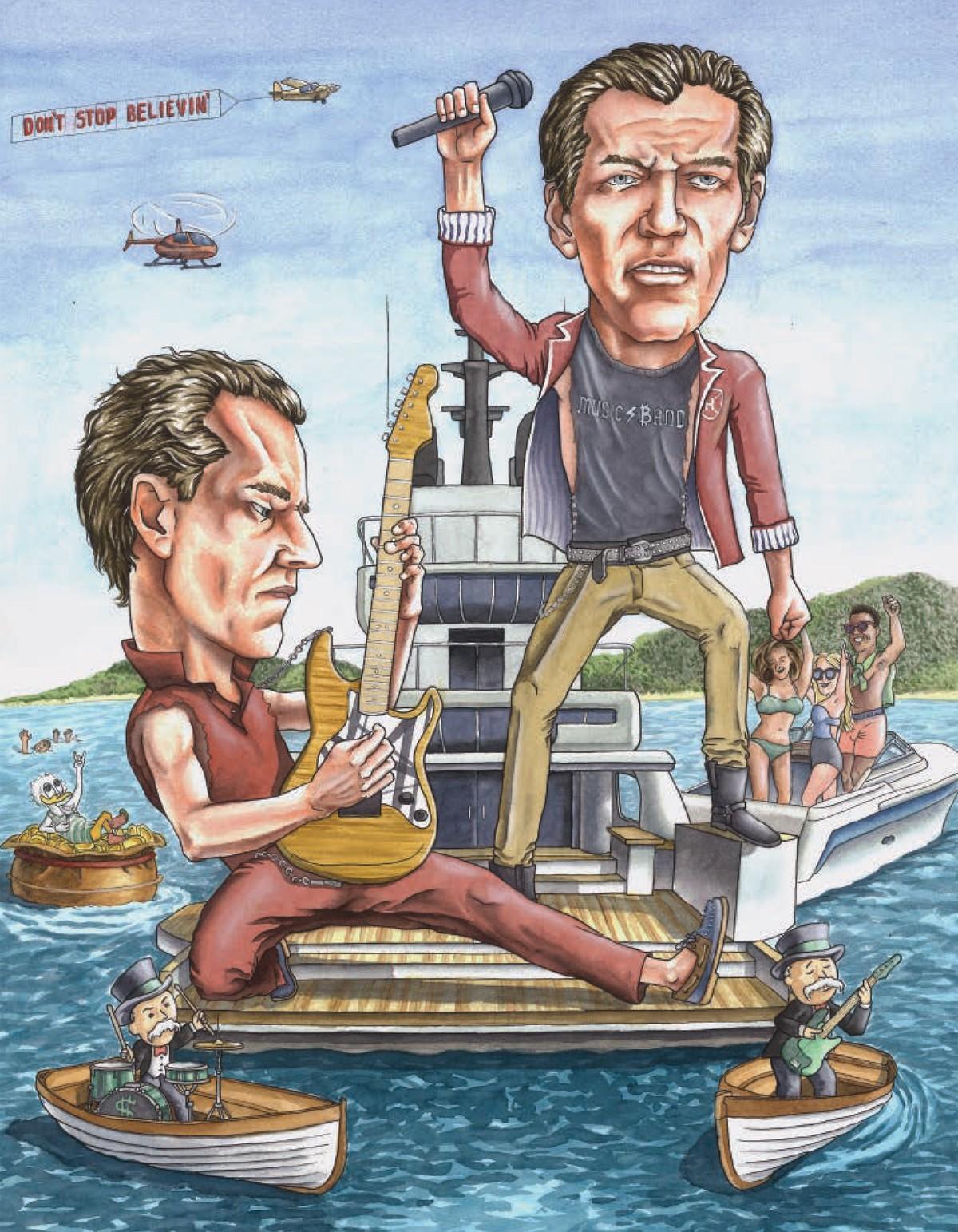

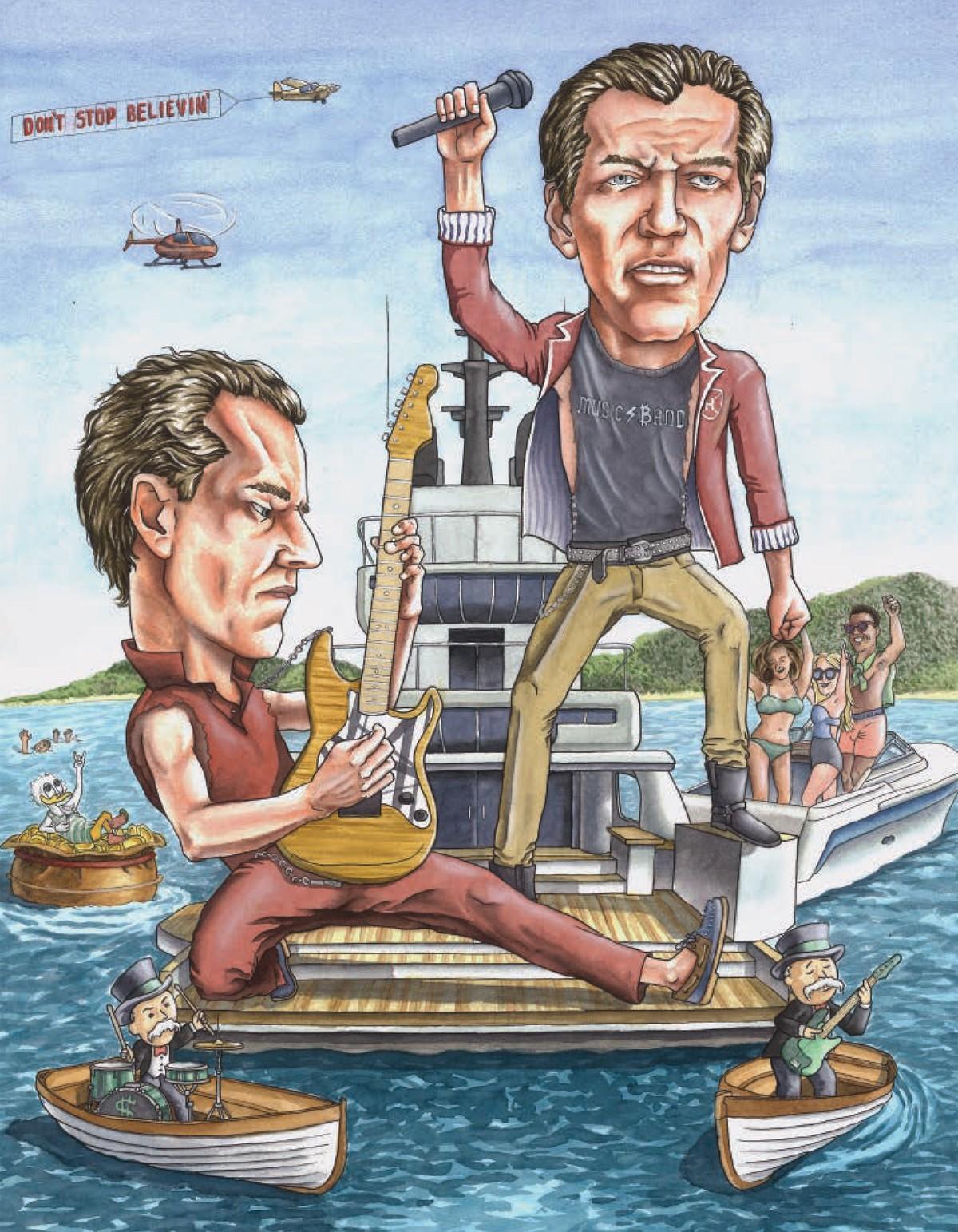

COMPLIANCE ROCK O’CLOCK

A look at the recent trend of billionaire CEOs arrogant enough to think they can purchase rock-star status.

December 1, 2022

Loading...

A look at the recent trend of billionaire CEOs arrogant enough to think they can purchase rock-star status.

Loading...