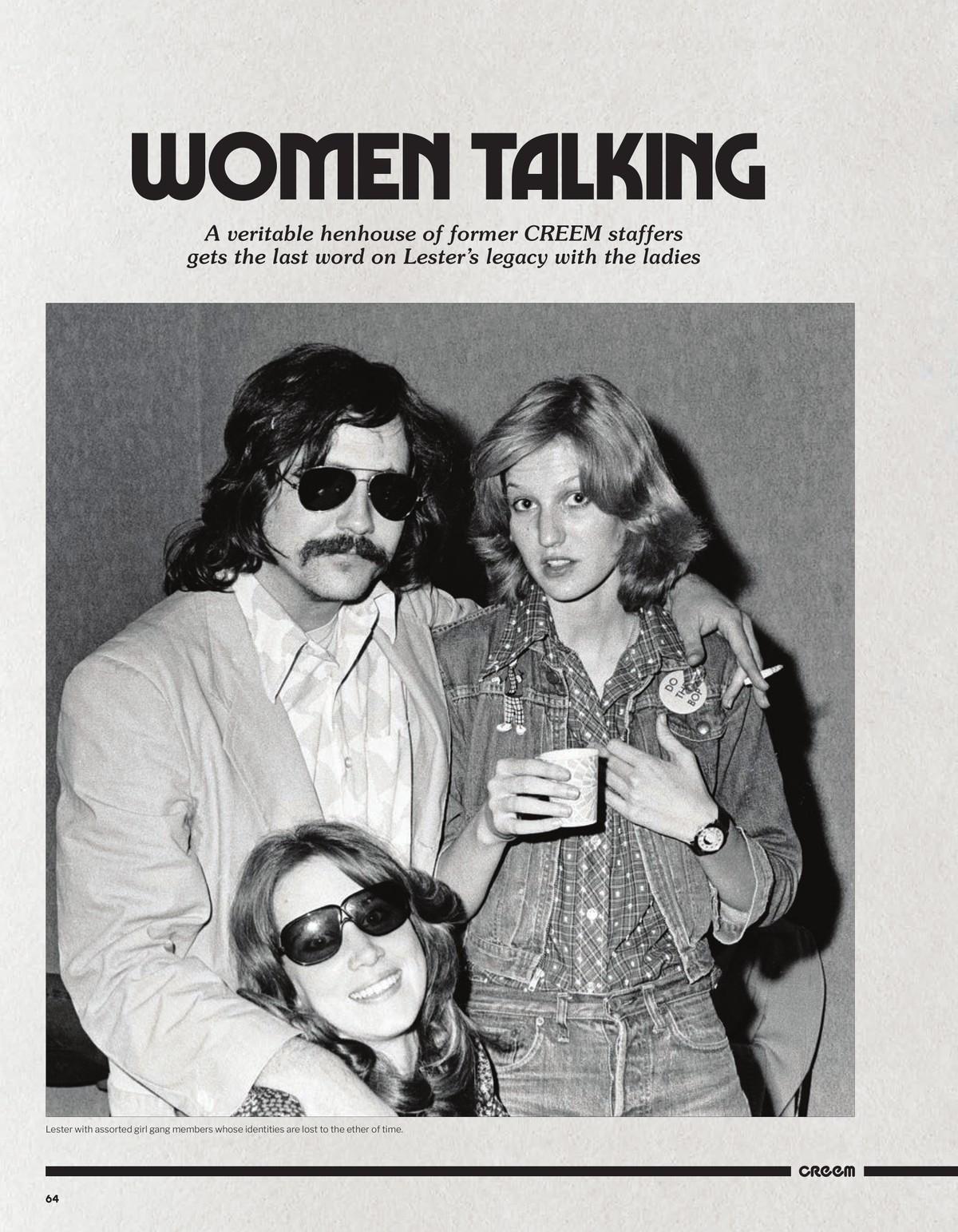

WOMEN TALKING

A veritable henhouse of former CREEM staffers gets the last word on Lester’s legacy with the ladies.

To become mythological is a tragedy almost Shakespearean in scale—you may have your fame and your legacy, but you lose something else in the process: your identity. Like any historical figure portrayed by Philip Seymour Hoffman in an Oscar-bait film, Lester Bangs has fallen victim to his own mythology. And when that happens, we forget the reality of who someone actually was.

On the one hand, he was undoubtedly one of a kind, the “king of dorks." He ushered in a new era of rock criticism on the literary foothills of Burroughs, Kerouac, and others. But let’s be frank—his writing doesn’t read well in this painfully virtuous present moment, what with its underlying racism, sexism, and homophobia. And that’s a valid bone to pick.