BAD AND PROUD

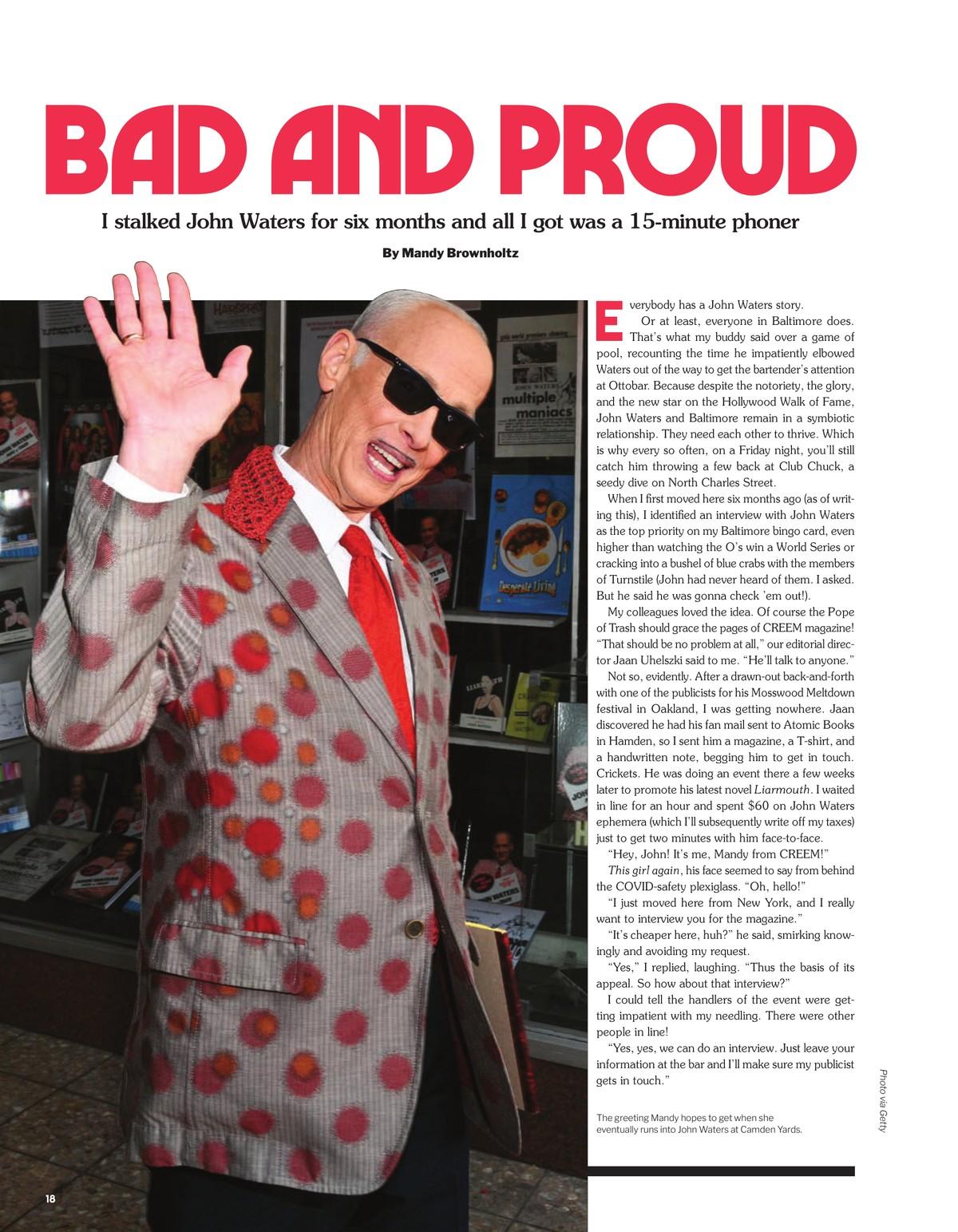

I stalked John Waters for six months and all I got was a 15-minute phoner.

Everybody has a John Waters story. Or at least, everyone in Baltimore does. That’s what my buddy said over a game of pool, recounting the time he impatiently elbowed Waters out of the way to get the bartender’s attention at Ottobar. Because despite the notoriety, the glory, and the new star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, John Waters and Baltimore remain in a symbiotic relationship. They need each other to thrive. Which is why every so often, on a Friday night, you’ll still catch him throwing a few back at Club Chuck, a seedy dive on North Charles Street.

When I first moved here six months ago (as of writing this), I identified an interview with John Waters as the top priority on my Baltimore bingo card, even higher than watching the O’s win a World Series or cracking into a bushel of blue crabs with the members of Turnstile (John had never heard of them. I asked. But he said he was gonna check ’em out!).