Police Files

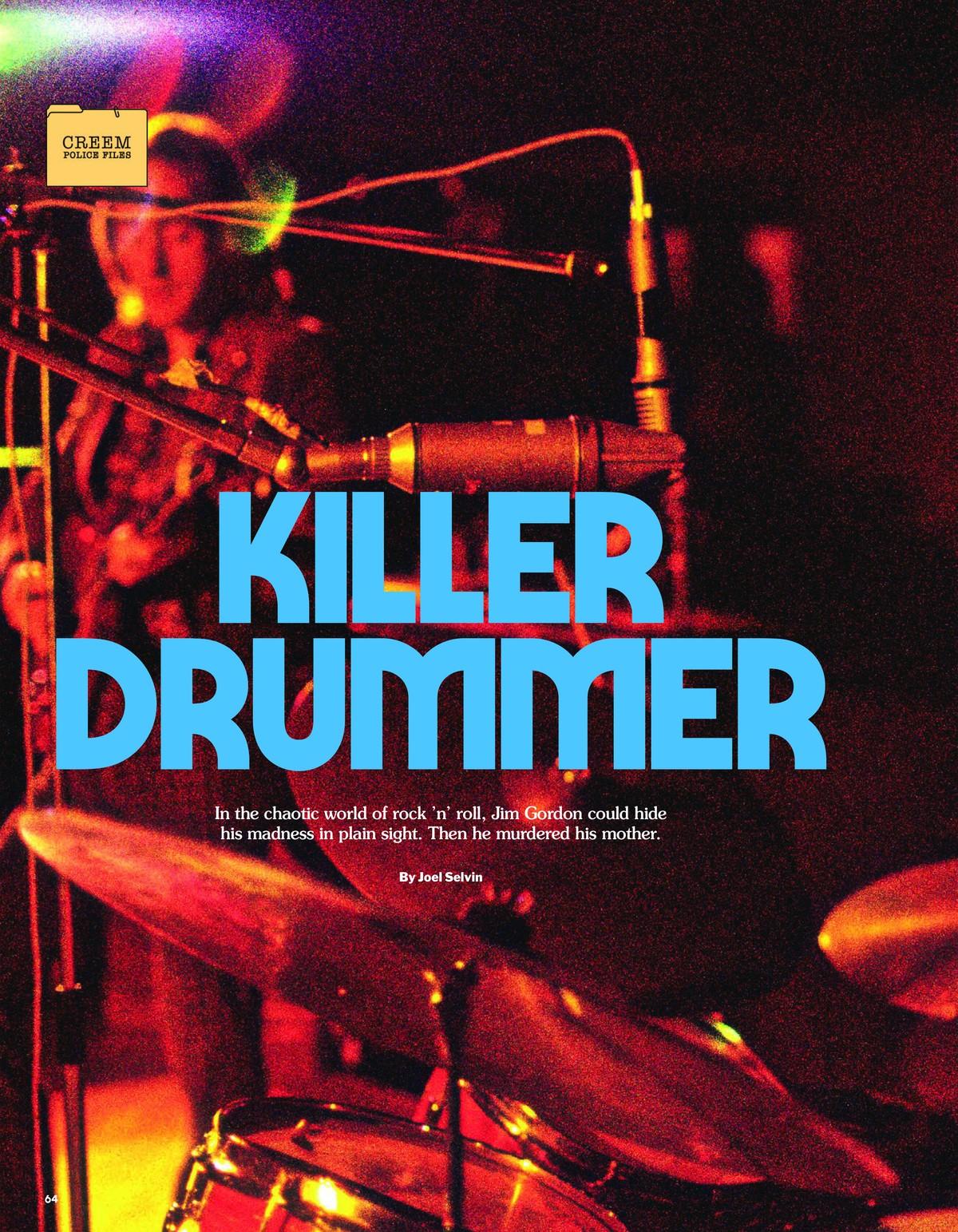

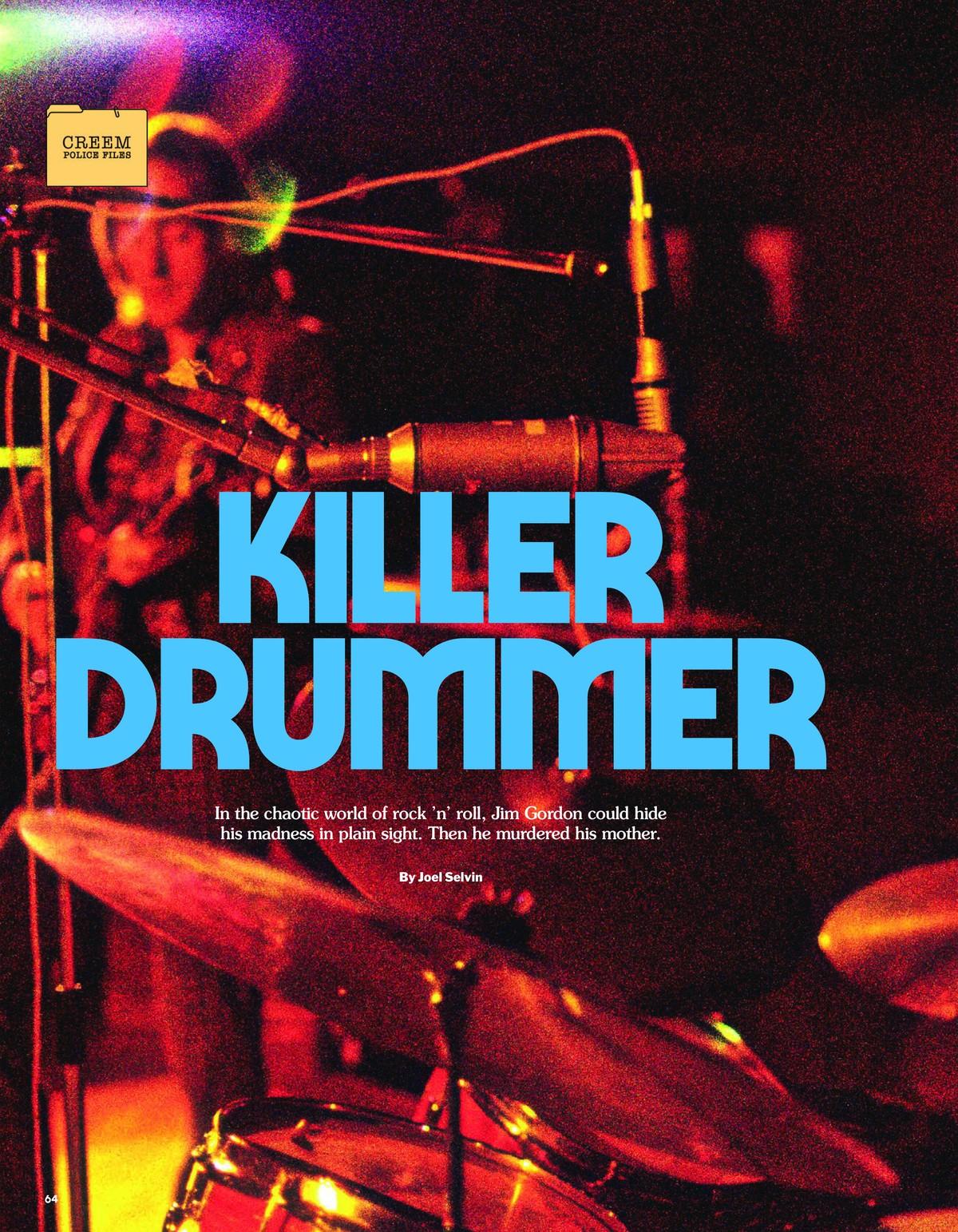

KILLER DRUMMER

In the chaotic world of rock 'n' roll, Jim Gordon could hide his madness in plain sight. Then he murdered his mother.

September 1, 2023

Loading...

In the chaotic world of rock 'n' roll, Jim Gordon could hide his madness in plain sight. Then he murdered his mother.

Loading...