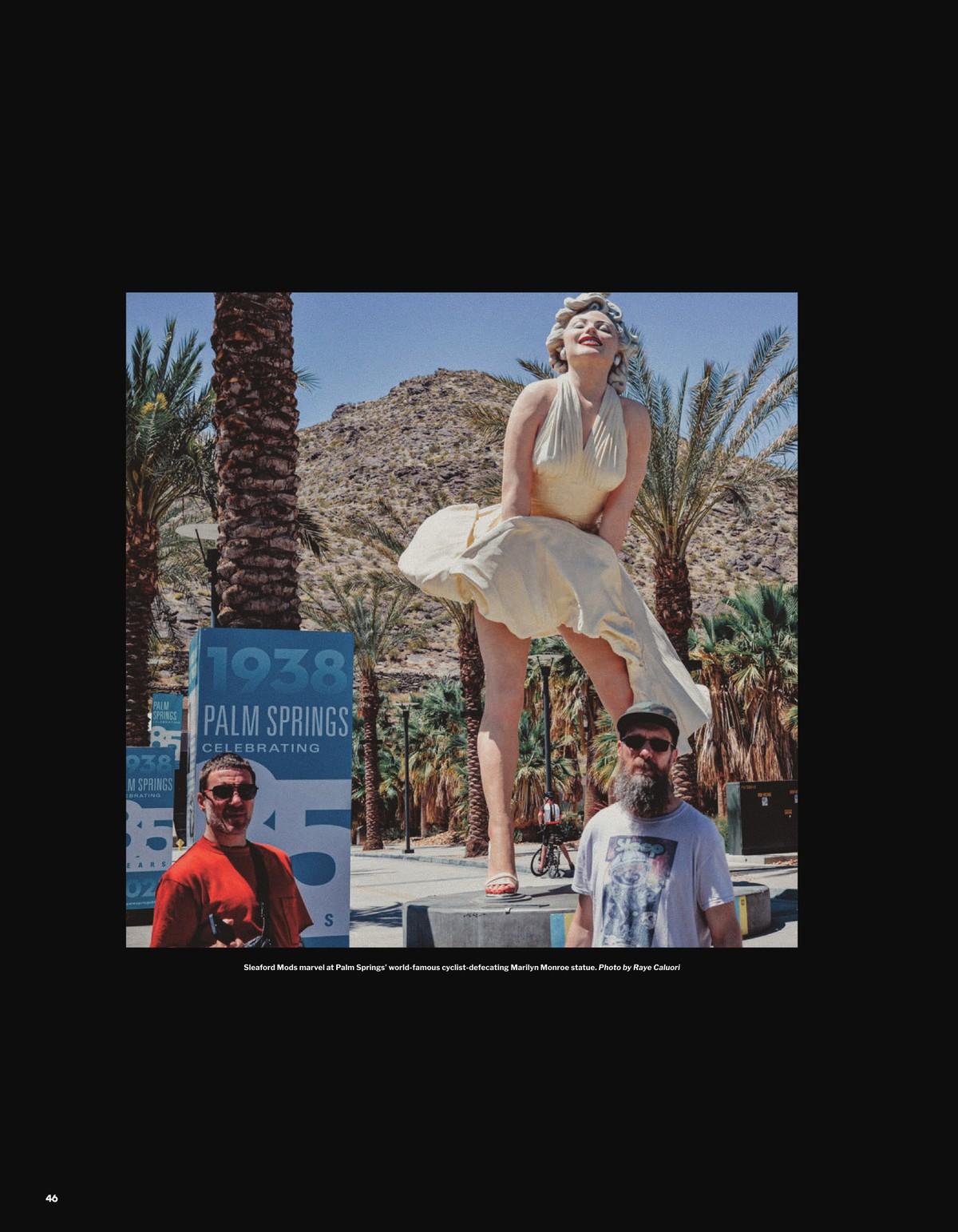

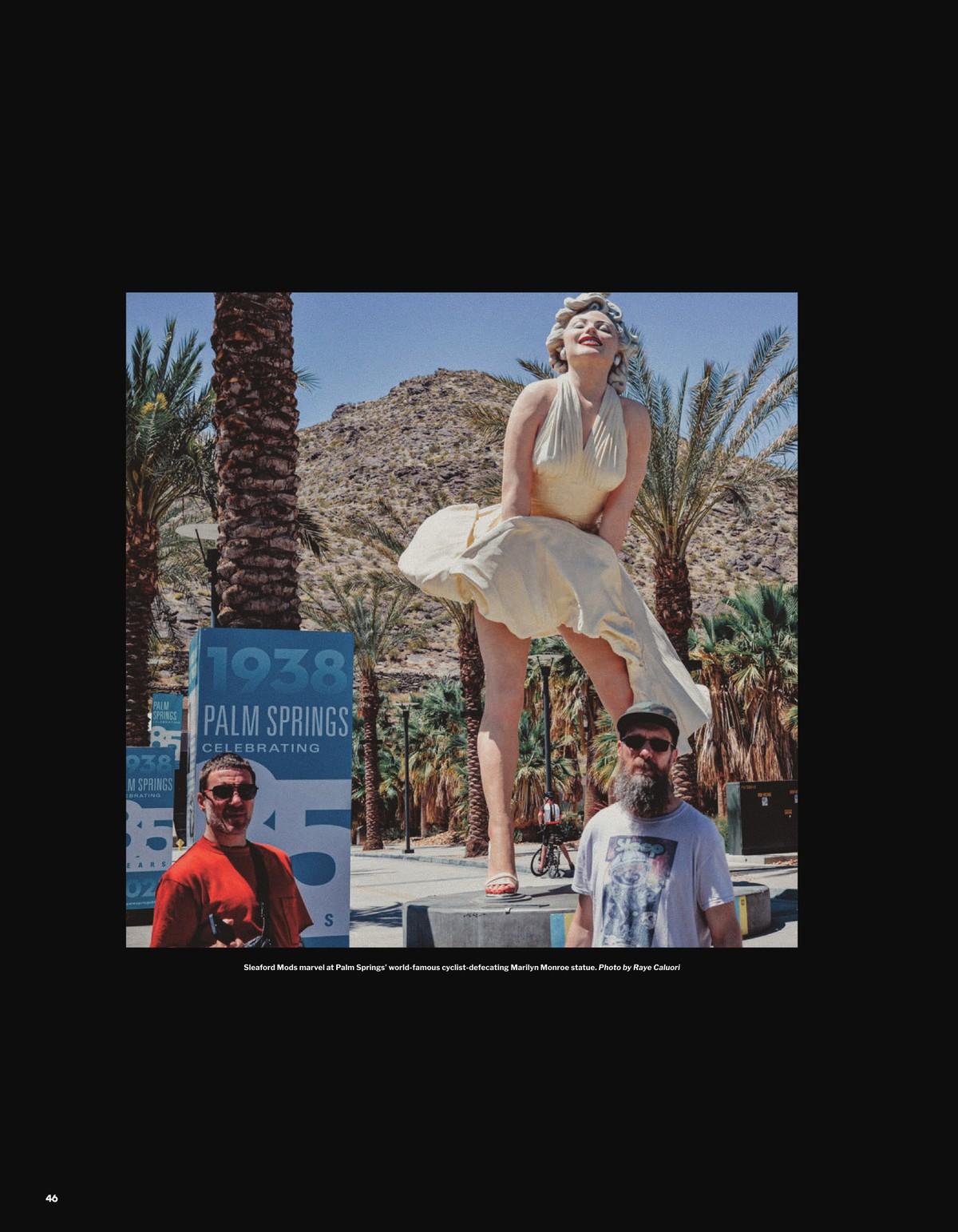

SLEAFORDS ARE DOING IT FOR THEMSELVES

Coachella takes place in a desert. Do people not have a working understanding The grim U.K. duo bring sand to the desert.

June 1, 2023

Loading...

Coachella takes place in a desert. Do people not have a working understanding The grim U.K. duo bring sand to the desert.

Loading...