Dusty Fingers

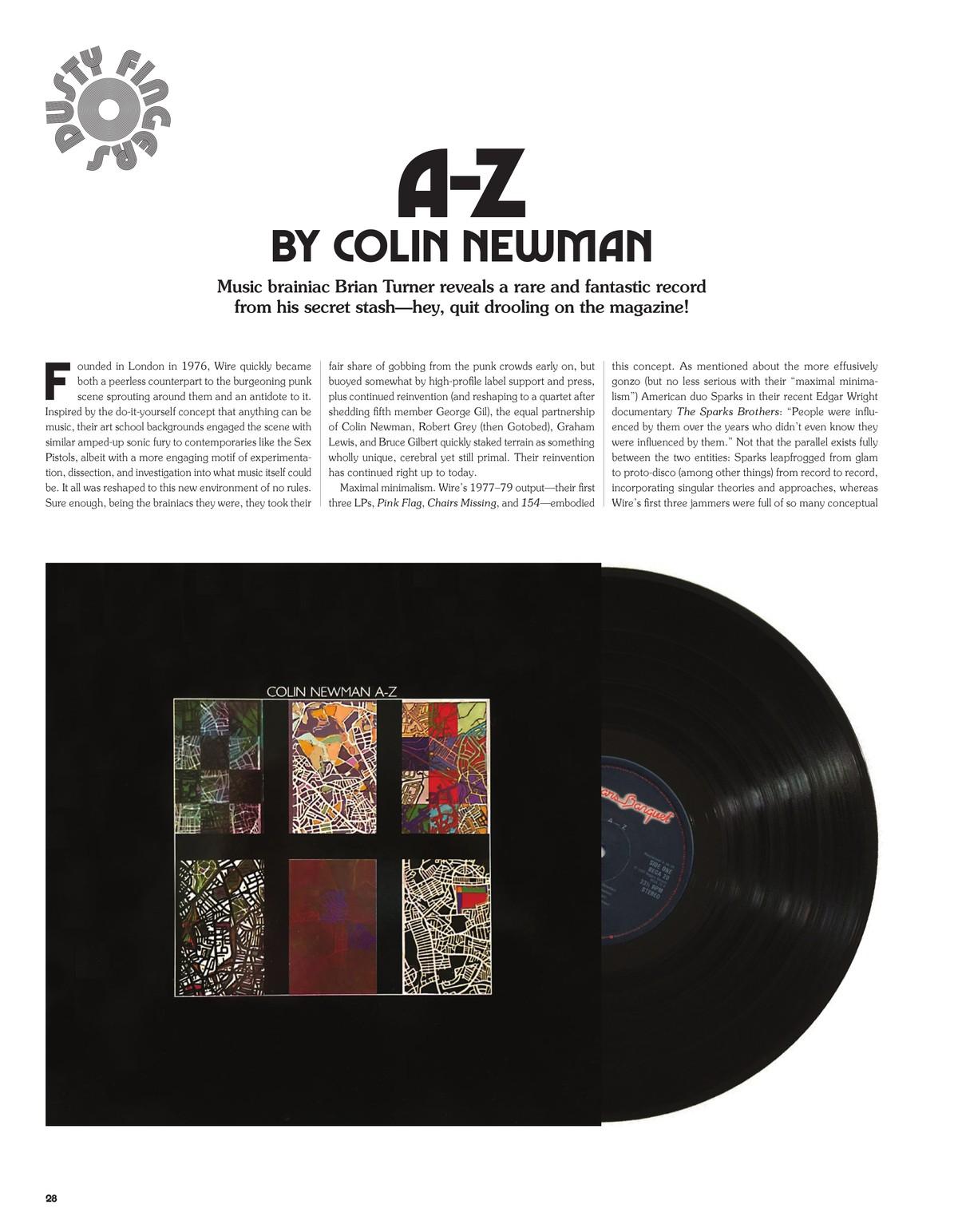

A-Z

Music brainiac Brian Turner reveals a rare and fantastic record from his secret stash—hey, quit drooling on the magazine!

June 1, 2023

Loading...

Music brainiac Brian Turner reveals a rare and fantastic record from his secret stash—hey, quit drooling on the magazine!

Loading...