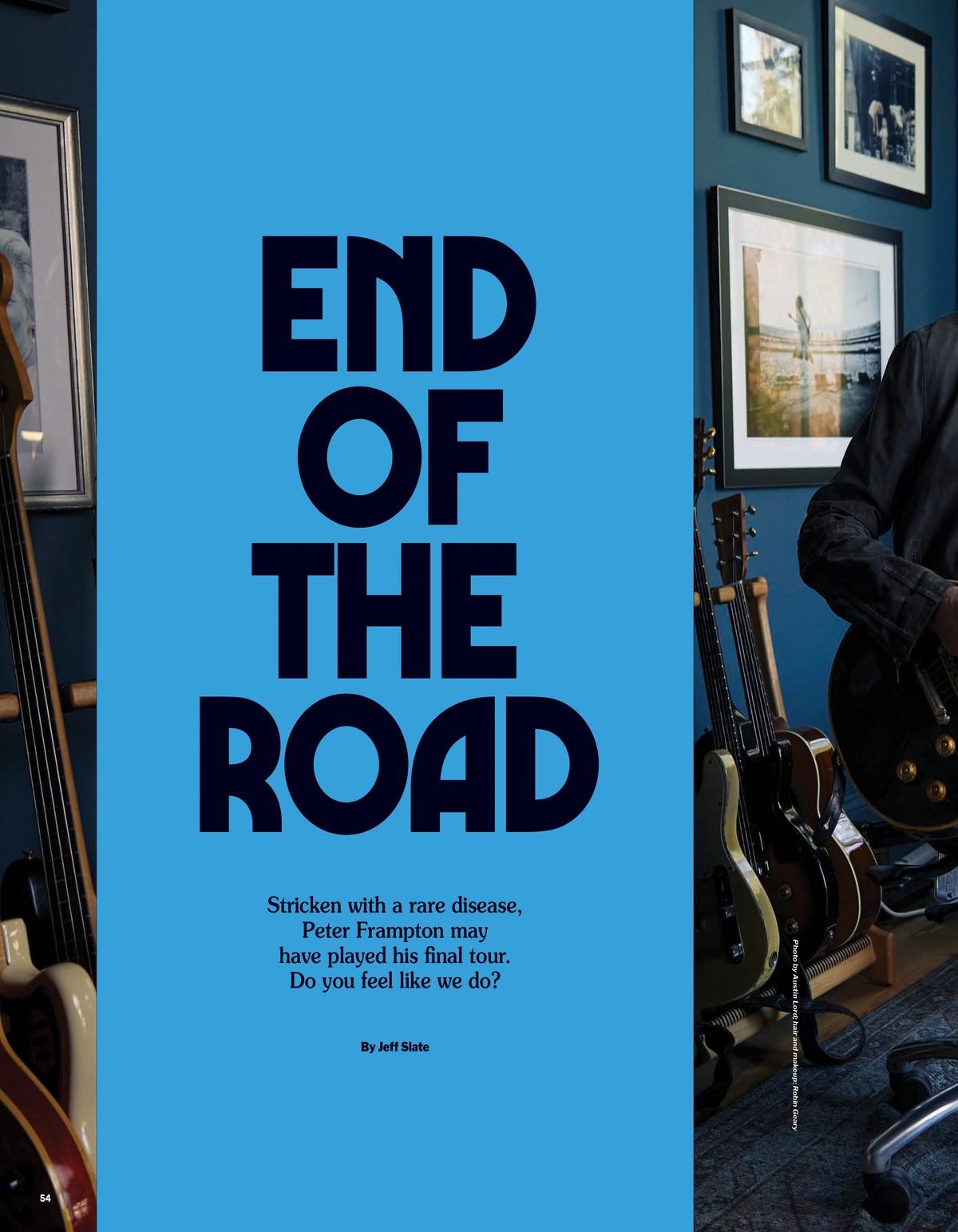

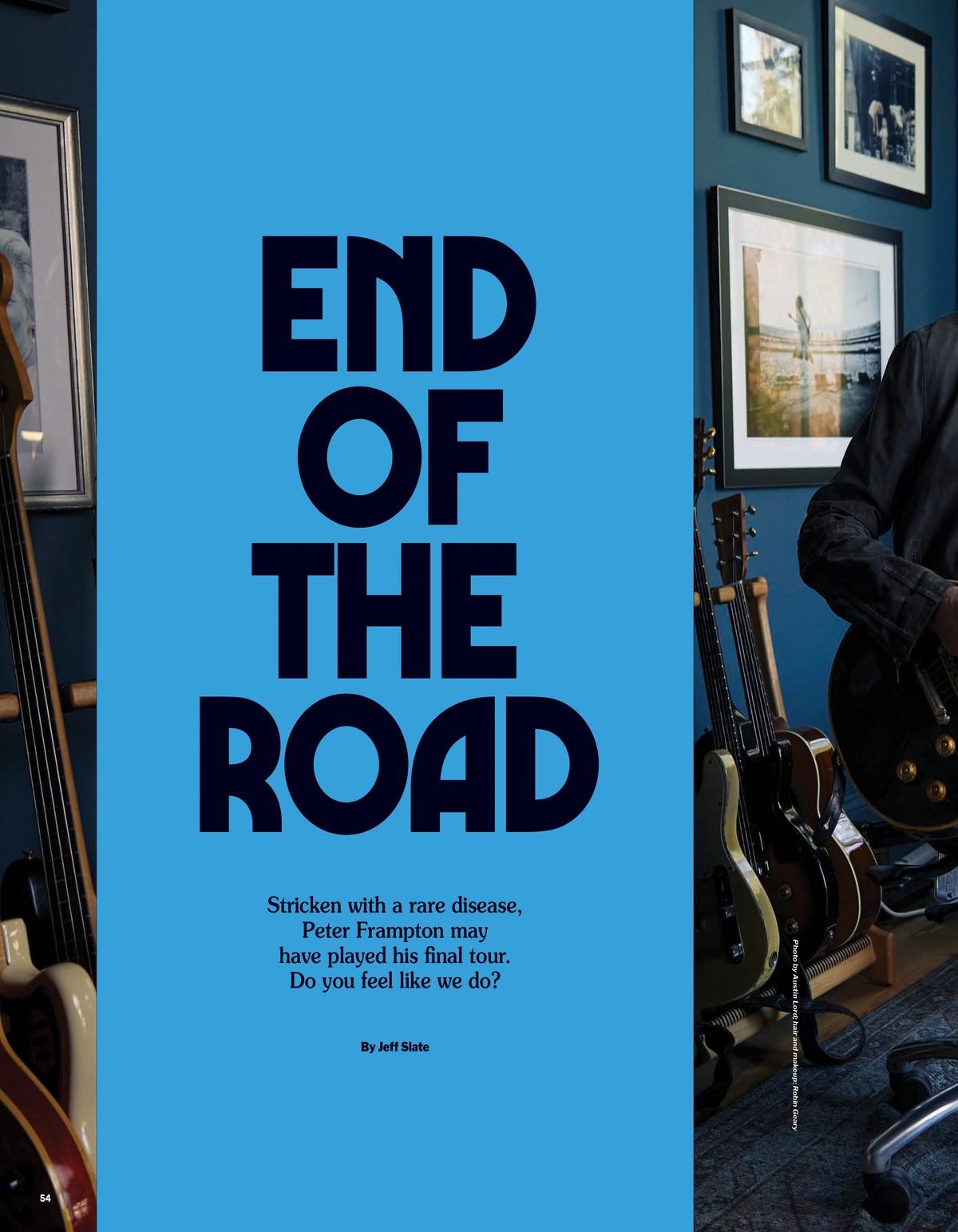

END OF THE ROAD

Stricken with a rare disease, Peter Frampton may have played his final tour. Do you feel like we do?

March 1, 2023

Loading...

Stricken with a rare disease, Peter Frampton may have played his final tour. Do you feel like we do?

Loading...