Police Files

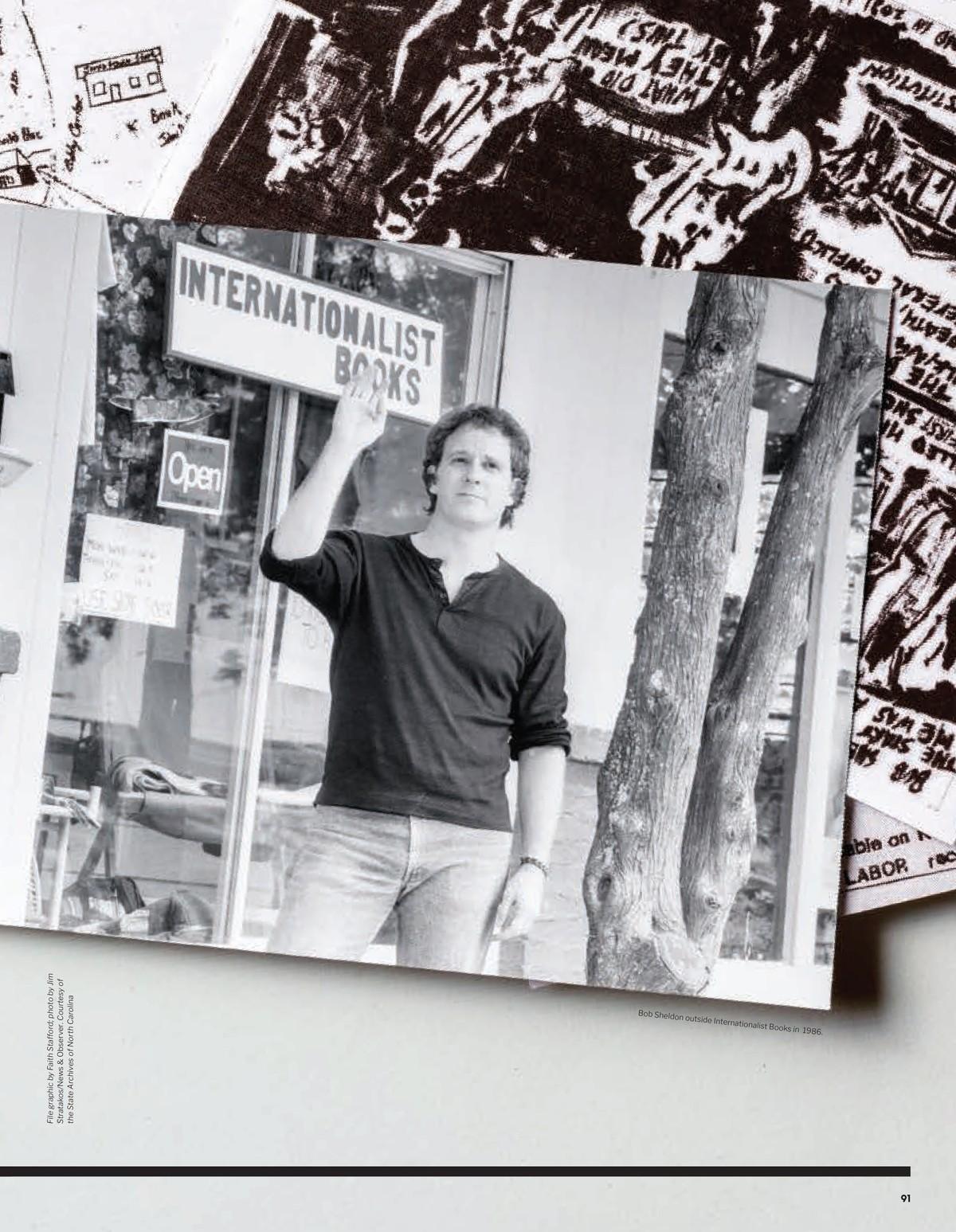

MURDER BALLAD

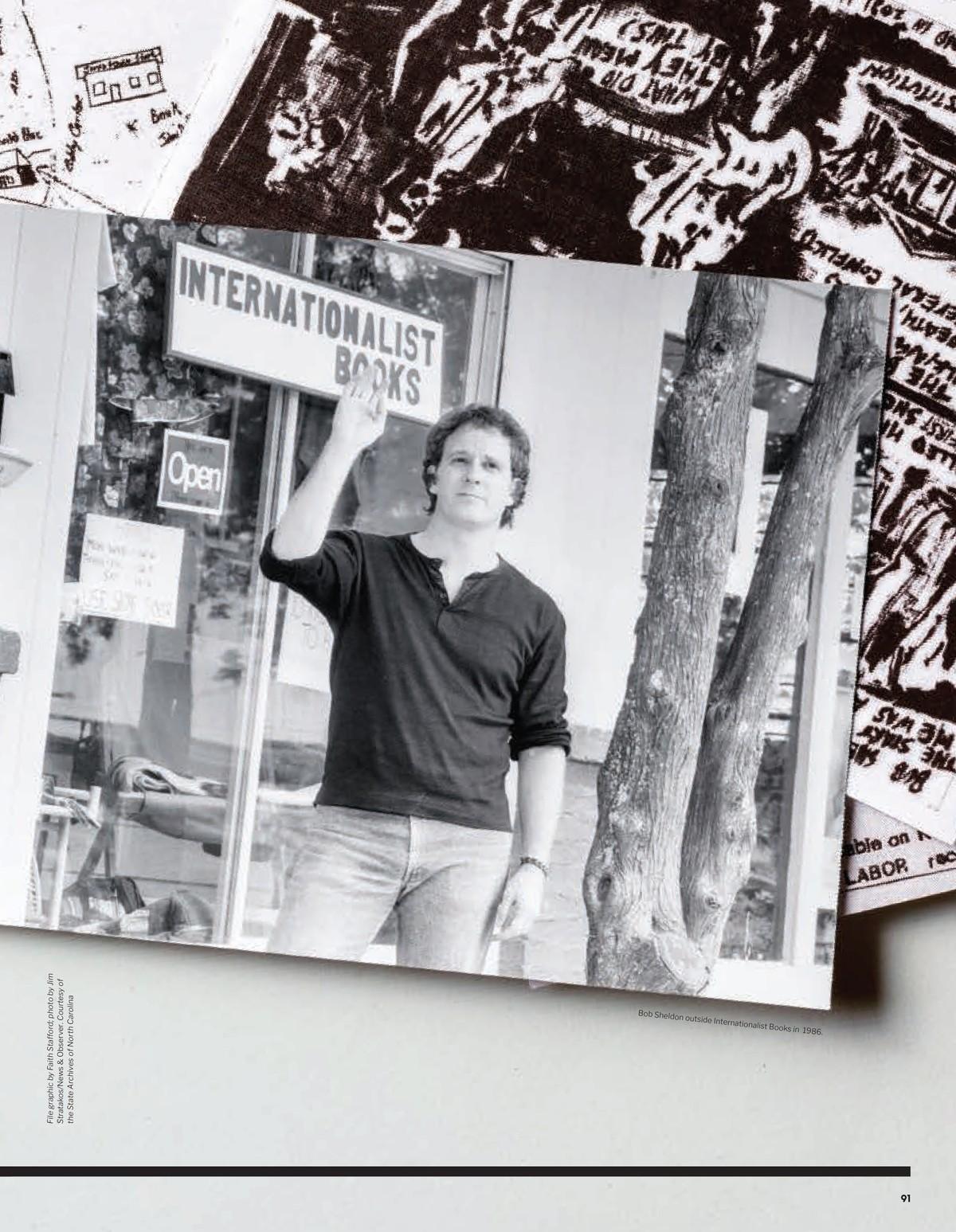

A Southern music mecca, a Sonic Youth shout-out, and the killing of communist bookstore owner Bob Sheldon.

September 1, 2022

Loading...

A Southern music mecca, a Sonic Youth shout-out, and the killing of communist bookstore owner Bob Sheldon.

Loading...