Records

Low Yo-Yo Stuff: Getting Closer to the Captain

Even though his music has always been solidly rooted in the blues, Beefheart has remained a sort of cult figure: to his followers, a supreme genius, to many others inaccessible both musically and verbally.

The CREEM Archive presents the magazine as originally created. Digital text has been scanned from its original print format and may contain formatting quirks and inconsistencies.

Low Yo-Yo Stuff: Getting Closer to the Captain

CAPTAIN BEEFHEART & HIS MAGIC BAND Clear Spot (Reprise)

“And that pantalooned duck/white goose neck/ quacked, ‘Webcor, Webcor.’” Those are the last lines on Clear Spot, from a song called “Golden Birdies.” Not exactly “I Can See Clearly Now,” I know, but if you find it hard to make sense out of lyrics like that, or feel that you must, rest easy. Captain Beefheart has come out of the haze.

Even though his music has always been solidly rooted in the blues, Beefheart has remained a sort of cult figure: to his followers, a supreme genius, to many others inaccessible both musically and verbally. Starting from Delta blues, which was never too rhythmically stable to begin with, Beefheart worked his way through rock and free jazz to build a totally original form of music. He handpicked and slowly trained the members of the Magic Band in the disciplines of a style which seemed to move from every angle at once, ricocheting back at you from the ceiling, feeling rhythmically askew yet never out of control. It took awhile, but once you got behind it, it could be breathtakingly powerful music, never sacrificing emotion for its avant-garde stance.

The words to his songs fell all around the music in a similarly coherent clatter. Beefheart’s mind works in a unique way: you can’t always get to what he’s talking about, but it’s almost always been effective as impressionistic imagery. Besides, you know what a line like “Yella jackets and red devils/ Buzz around ’er hair hive hole” means. Many of the songs set Beefheart up as a sort of off the wall oracle relating oblique fairy tales and parables that were diffuse enough to mean whatever you wanted them to but seldom pretentious. And anybody who sings about “Mama flattenin’ lard with her red enamel rollin’ pin” can’t be too strange.

The only trouble with all this was that most people didn’t have the time, or the musical exposure, or the attention span, or whatever was required to get into this music fully. And Captain Beefheart, just like every other stout hearted American, has always wanted to be a star. A rock’n’roll star. No matter how brilliant you and your limited circle of fans know you are, it’s never going to matter as much as it should if it’s not universal enough to be relatable to people who don’t want to be bothered with something that doesn’t hit them over the head and get their gonads right away.

Beefheart made a strong step in this direction with his last album, The Spotlight Kid. It was the easiest listening since his early, pro-Trout Mask Replica work, but somehow it missed. There was a certain tentative quality to it that disappointed some of his old fans and didn’t really win that many new ones. With Clear Spot, though, he’s gained his ground and looks to hold it for awhile. Which is just another way of saying that the Captain may have a hit on this deck, folks.

It’s ironic in a way, because one thing this album proves is that the ascendance of Boogie has merely brought the masses that much closer to Beefheart and Beefheart’s roots. Meanwhile the man himself has tightened and directed his music for a new kind of concise fury. The words are as rangy as ever (except for some love ballads and specific sex grope chants) but their splintered refractions hit home more often than not. They’re the perfect crest for the dominant mode of Clear Spot, which is a surging tide of sound: rusty, demonic guitar flailing, raspy voied choking, punching, roaring and pounding drums underneath it all. Everything is pouring in and it’s all instantly relatable. You can still hear meshes of Bo Diddley, square dance, bebop, African drum and maybe European folk dance in Beefheart’s chunky loping rhythms, but somehow you never lose the heartbeat of rock’n’roll.

“Nowadays A Woman’s Gotta Hit A Man” is a perfect example of how Beefheart mates musical culture: old blues, Stax horns doing a New Orleans boogie, slashing amped-up bottleneck guitar, Beefheart’s incredible growls gouging and rambling all over the place. “Low Yo Yo StufF’ is hypnotically compelling, with deep booming rhythms and upfront guitar. His old stuff showed a thorough absorption of free jazz masters like Ornette Coleman; here it’s used as seasoning, because the basic impetus is funk all the way, gravel ’n’ greasy, with a bit of juju out of (though not derivative of ) Dr. John. And the words are a total gas — in an effete era Beefheart slides on with the universal joy of good old fashioned non-ambivalent lust.

“Too Much Time” and the ballads “My Head Is My Only House Unless It Rains” and “Her Eyes Are A Blue Million Miles” are all ventures into more or less new ground for Beefheart. “Too Much Time” seems rather strained — Otis he ain’t (which is no denigration; he can do things Otis couldn’t), and the horns seem rather perfunctory, lacking the edge and fullness that Stax gives the same cliches. The female vocal backup, as elsewhere on the album, is pleasant but seems almost like an afterthought or an attempt to give this album a marketable trendiness it doesn’t really need.

“Head” and “Eyes” are both delivered with enormous tenderness, yet somehow Beefheart’s gruff voice sounds out of character with material like this, as if it’s just about to rant through the walls of the cut and start thrashing in the brambles once again. Still, both songs wear well, and “Eyes” is especially fine for some low, lovely mandolin work.

The main thing to be said about this album is that, even at its most violent, it’s comfortable. Its scope becomes endless by limiting itself (how’s that for rock critic bullshit?) and you can throw it on anytime. It feels good to listen to Clear Spot, and it feels good to know that Beefheart has finally become a bit less of a phantasmal, somewhat arcane father figure and come into his own as a flat-out, full-throttle rock ’n’ roller. If this LP jives your buns the way it should, though, you should waste no time in securing a copy of the earlier, two-record Trout Mask Replied. That’s one of the most overwhelming pieces of music ever recorded.

Lester Bangs

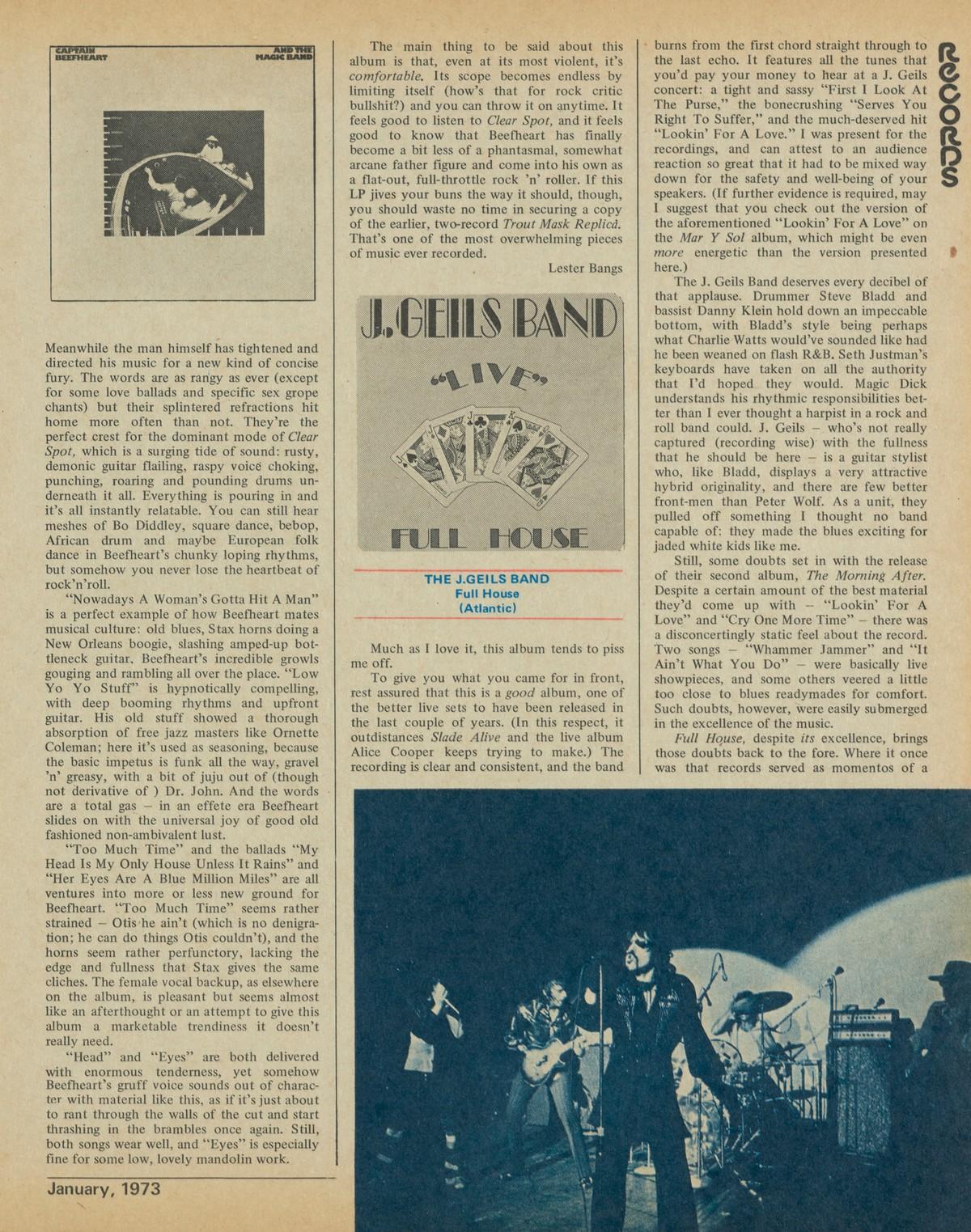

THE J.GEILS BAND Full House (Atlantic)

Much as I love it, this album tends to piss me off.

To give you what you came for in front, rest assured that this is a good album, one of the better live sets to have been released in the last couple of years. (In this respect, it outdistances Slade Alive and the live album Alice Cooper keeps trying to make.) The recording is clear and consistent, and the band burns from the first chord straight through to the last echo. It features all the tunes that you’d pay your money to hear at a J. Geils concert: a tight and sassy “First I Look At The Purse,” the bonecrushing “Serves You Right To Suffer,” and the much-deserved hit “Lookin’ For A Love.” I was present for the recordings, and can attest to an audience reaction so great that it had to be mixed way down for the safety and well-being of your speakers. (If further evidence is required, may I suggest that you check out the version of the aforementioned “Lookin’ For A Love” on the Mar Y Sol album, which might be even more energetic than the version presented here.)

The J. Geils Band deserves every decibel of that applause. Drummer Steve Bladd and bassist Danny Klein hold down an impeccable bottom, with Bladd’s style being perhaps what Charlie Watts would’ve sounded like had he been weaned on flash R&B. Seth Justman’s keyboards have taken on all the authority that I’d hoped they would. Magic Dick understands his rhythmic responsibilities better than I ever thought a harpist in a rock and roll band could. J. Geils — who’s not really captured (recording wise) with the fullness that he should be here — is a guitar stylist who, like Bladd, displays a very attractive hybrid originality, and there are few better front-men than Peter Wolf. As a unit, they pulled off something I thought no band capable of: they made the blues exciting for jaded white kids like me.

Still, some doubts set in with the release of their second album, The Morning After. Despite a certain amount of the best material they’d come up with — “Lookin’ For A Love” and “Cry One More Time” - there was a disconcertingly static feel about the record. Two songs — “Whammer Jammer” and “It Ain’t What You Do” — were basically live showpieces, and some others veered a little too close to blues readymades for comfort. Such doubts, however, were easily submerged in the excellence of the music.

Full Hqy.se, despite its excellence, brings those doubts back to the fore. Where it once was that records served as momentos of a good live show, the J. Geils Band seems to be threatening to reverse that maxim. It’s not even so much that all eight cuts here are available on the two preceding albums (and that many have actually been fixtures of their sets for as long as three years) but a problem of which this fact is only a surface manifestation.

The simple truth is that the J. Geils Band hasn’t given itself enough room to grow. They are a wording band in the old-fashioned R&B sense — which is the level on which this album makes most sense — but the endless one-night grind is hardly conducive to a normal growth process. As a result, there’s very little for them to fall back on except the set they’ve programmed and the mutual readymades they can most quickly summon to mind.

This band is now at the stage which the Stones were at with Now: still largely reliant on their root forms (blues) but with every indication that they can become something truly explosive for the times in which they exist. The static* overtones of Full House should not be taken to mean that this potential is being abused in any way, but only that they’ve got to give themselves a little more room to move and a little more time with which to do it. The potential of the J. Geils Band says that there’s no reason why they couldn’t develop into the finest rock and roll band in the land, and to let them get away with anything less would be a crime of monumental proportions.

Ben Edmonds

CAT STEVENS Catch Bull at'Four (A&M)

ALUN DAVIES Daydo (Columbia)

While in the sanitarium, Cat Stevens plotted his second career shrewdly. He sensed a vacuum and moved in. Donovan had faded away, the Incredible String Band had palled:, and suddenly there was no reigning minstrel. So Cat gave us everything Donovan had previously supplied: a childlike sweetness, a sense of fragile mystery, and a dollop of personal idiosyncrasies. The fairy tales, even the album covers, recalled Donovan: their appeal was identical.

But there has always been an incongruous growl in Cat’s voice, a harshness out of keeping with the delicate pose, and from the beginning a stronger sexual drive than the role of darling youth could contain. Sex and a growl, of course, are more at home in rock’n’roll, which Cat and Catch Bull at Four seem to be moving toward.

The Cat’s not entirely out of the old bag yet. “The Boy with the Moon and Star on his Head,” suggested, I think, by an Oscar Wilde fairy tale, “The Star-Child,” is in the minstrel mode. So is “Silent Sunlight,” a reprise of “Morning is Broken.” But a line like “I’m up for your love” in a song entitled “Can’t Keep It In” is a long way from Donovan, and fully half the tracks on Catch Bull might be called rockers.

But can Cat pull it off? Intermittently but not consistently, and for several reasons. First, Cat’s fondness for quirky, broken rhythms, which made his folkier tunes that much more interesting, keeps his rock from rolling. Secondly, no longer compelled to affect gentleness, Cat tends to go to the other extreme and become absurdly gruff and melodramatic. Occasionally he seems even to be parodying Family’s Roger Chapman, whose own voice may ultimately be a parody of Robin Gibb’s (of T)»e BeeGees). Finally, there’s the band. Jean Roussel’s stiff piano and Alun Davies’ acoustic guitar are hardly the stuff of which great rock is made. The music is often comically thin. Cat tries to beef it up by recording his voice too loudly or with echo, by playing synthesizer and electric piano and guitar, and by jazzing up the tracks with gimmicky sound effects, but it’s not enough.

The album’s most successful cut seeks a middle ground between folk and rock, the turf Tim Hardin and James Taylor (“Fire and Rain,” for example) have occupied. Given his band, this is the natural place for Cat to be. “18th Avenue (Kansas City Nightmare)” is a chilling encounter with and flight from meaninglessness conducted by Cat’s spare electric piano. The lyric is exceptional and the restrained vocal the album’s best. Except for a passage in which Del Newman’s string arrangement becomes too Jim Webbish, this is a perfect track.

And there are other fine things on the album; indeed every cut has its interesting moments. But Catch Bull is not a satisfying album. It creates expectations it cannot fulfill, and the means at its disposal are not adequate to realize the ends it proposes.

Daydo, the album Cat’s acoustic guitarist has made with help from the rest of the band (Cat and Paul Samwell-Smith produced it) is at first disconcerting, as it seems to wander from rock to tripping-down-thecobblestones pop/folk to self-conscious art to larf-and-sing. This lack of focus is not helped by Davies’ voice, which has no consistent or definite character (Elton John and Cat are the two dissimilar singers he most often sounds like). I found, however, that with repeated listenings the record acquired increasing charm, and after two weeks I quite liked it Daydo is a lovely minor album.

The arty numbers are the most attractive. They’re generally slow and sentimental, with odd stop-andtgo rhyflhms. What distinguishes them are their genuinely beautiful melodies, relatively intelligent lyrics, and intriguing arrangements. “Market Place,” for instance, is mostly scored for just acoustic guitar and bass drum, with a haunting oboe (or is it a soprano sax?) obbligato. “Vale of Tears” is merely organ and guitar playing muted, delicate counterpoint. The sophisticated simplicity of these songs is beguiling and somehow never precious. When the music is more elaborate (“Old Bourbon,” “Waste of Time”) the results are not nearly so arresting.

I won’t call Daydo an auspicious debut — that sounds too pompous — but it is delightful.

Ken Emerson

PETE TOWNSHEND Who Came First (Decca)

JOHN ENTWISTLE Whistle Rymes (Decca)

Now that I’ve decided I even like Tommy, I feel a lot more secure about not liking Who solo albums. Both of these are valid attempts, but anyone who tells you either succeeds in anything like the way it could - or should - is buffaloing himself.

I am inclined to believe that Meher Baba is probably the best spiritual master Pete could have, if he has to have one. Baba books and such have always seemed trite to me, without a whole lot to add to the body of cosmic aphorisms, but since he spent most of his life in silence, one doesn’t expect much. Whatever Townshend finds in Baba, he generally tempers it well, without the humorless posturing John McLaughlin, for one, has lost me with.

But, liking Baba and Townshend and the Who as much .as I really do, I still don’t like much about Who Came First. It’s inconsequential stuff, for the most part, and one of the best songs on it, Ronnie Lane’s “Evolution,” is almost indistinguishable from the version on the Faces’ first album. The other two good ones are much better: “Let’s See Action,” a song which the Who made a British hit and which is something like the answer to the quandry that “Won’t Get Fooled Again” set up, is far superior to the single version, with a lot more texture. Its philosophy is a lot clearer, as well. It’s not a great song, as these things go, but it’s a lot better — and a lot more honest — than “Join Together With the Band,” which was mostly just an AM annoyance. “Heartache,” which is a remake of Baba’s p’ck-hit of the lifetime, “There’s A Heartache Following Me,” by Jim Reeves, is just good music. Nothing special, really, although it says a lot more about why people engage in guru pursuit than anything any other rock star has shoved down our throat.

Not that Townshend shoves anything here. Who Came First is there, if you want it, which I don’t suppose I do, particularly. It’s a curiosity, more than anything, or an idiosyncrasy. But what I really want to get at is that Townshend has the best perspective on all this cosmic jive, that he is sincere and that if Baba is the most important influence in his life, it’s probably been a good influence, for the most part. I would rather recommend the Meher Baba benefit album, with the long instrumental version of “Baba O’Reilly,” though. It really is far superior to anything here, with all the fire and imagination I’d hoped for from this solo work.

I don’t think most of John Entwistle’s music makes it, which isn’t surprising since Smash Your Head Against the Wall was too good to be true in the first place. The music on Whistle Rymes is mostly innocuous, not the heavy-metal of Smash, and the lyrics are even more sinister than before. If Chuck Berry is bidding to become the Russ Meyer of rock’n’roll, Entwistle probably has designs to be its Alfred Hitchcock. If Randy Newman doesn’t beat him to it — and Newman is more like Roger Corman, anyway — he probably will be. This is a good record for Who fans, but like Townshend’s, it requires a certain quality of obsession.

Nothing else this year has been worth a fuck, and these records aren’t horrible. I don’t expect much, and they don’t deliver except insofar as they are a reflection of the general doldrums we’re experiencing. Maybe, as Bob Christgau suggests, albums are over, for awhile at least. I could do with another Whd tour, though, for openers. Meantime, I’m going back to the movies, or something.

Dave Marsh

BLACK SABBATH Volume Four (Warner Bros.)

Oh Jeez. The question is, would you rather have your Black Sabbath Volume 4 be. some sort of magnificent change of direction with the band loping down new and wondrous back alleys of musical mysticism, or would you prefer to have the same old shit and be bored again to a mindless husk? Volume 4, happily or unhappily, gives you the opportunity to have your wake and eat it too.

As far as the same old shit routine goes, seven of the nine cuts offered are just that. If you could make a composite tape of the first three Sab albums, Volume 4 would be it. Black Sabbath remain the uncompromising riff band, laying countless unimaginative lead riffs and stagnant echoed vocals over their one standard bass/drums background track. Granted, lots of bands follow basically this same formula, like Deep Purple for instance. But what makes a new Deep Purple album so much more listenable is that band’s knack of creating a seemingly endless number of catchy melodies from its few basic riffs. Black Sabbath generally play their one song to the point of exhaustion.

So then, suppose that you were a member of said band Black Sabbath. (For effect, you might just want to tear the buttons off your Mach II and expose some chest, or stuff a couple of cushions from your living room into your ears to feel just like one of the boys in concert.) You’re playing in a hockey arena in Pittsburgh, and your musical sensibilities have just been shocked by the realization that while you were playing “Iron Man,” the other guys in the band were playing “Children of the Grave.” As nobody mentioned the fact to you, you can safely assume that you got away with it this time. How does it make you feel? Blase? Confident? Or do you perhaps become aware of a need to chart new musical forces, add a little variety to the act, as it were. “Lads,” you bravely announce one day while relaxing in your 500 year old manor house that you just bought from John Lennon, “It’s time we got laid back. ”

And get laid back they do. Volume 4 presents two examples of the Black Sab Sound of Tomorrow. The first, entitled “Changes,” is a soft sounding number augmented by piano (tinkling, waterfall variety) and strings (standard Mantovani tune-up inspiration). By foregoing food and sleep for seventy-two straight hours, someone in the band was able to come up with these poignant lyrics to accompany the haunting melody:

I feel unhappy I feel so sad I lost the best friend I ever had She was my woman I loved her so But it’s too late now I’ve let her go.

Ain’t that something? A great interlude for side one. And for side two, a startlingly enchanting accoustic mood piece called (what else?) “Laguna Sunrise.” With a title like that, a description of the song would only be superfluous on my part.

Thus, the boys in the band have cleansed themselves of the need to get laid back, and can now happily resume their droning instrumental blitzkrieg. Wouldn’t it be great if we mere mortals could expurge our hang-ups, pimples, or diseases with such efficiency? Perhaps, but at least we still have our souls.

Alan Niester

LOUDON WAINWRIGHT III Album III (Columbia)

It’s impossible to forget the sight of Loudon Wainwright singing: head turned upward and wobbling loosely on his hunched shoulders, his face contorted in response to what appears to be some unbearable inner tormerit, his voice quaking and wreaking with vulnerability. His presence fuses the distinguishing elements of his songs — the wordplay, comic irony, self-parody pathos, and all the underlying despair — into a touching and often quite disturbing unity. It can get precious and pretentious sometimes, and it’s always neurotic, but he makes it all work for him. His best performances are like public self-exorcisms.

Wainwright’s first two albums (on Atlantic) are sketches of his live performance, with his acoustic guitar as the sole accompaniment to his vocals on most tracks. The stark sound serves Wainwright’s style nearly as well on record as it does on stage, and albums / and// provide accurate, though sometimes less than fully inspired, representations of that style (Wainwright, more than most artists, seems to need an audience’s focus to get a flame going under himself).

For his third Lp, Loudon has chosen a different course: he’s brought in a bunch of musicians to back him up on several tracks. The change in format is accompanied by a corresponding change in the nature of Wainwright’s songs. Most of them are noticeably less personal than those on the first two records; they’re a safe distance back from that edge of hysteria that Loudon has been so nimbly dancing along. They’re less intense, and this lessening of emotional pitch was an initial disappointment to me: I’m not nearly as caught up in Wainwright’s singing about a dead skunk in the road as I am in his desperately funny reflections on suicide, or his pictures of solitary childhood passions, or even his cataloguing of items noticed during a plane ride, with the unspoken but-still present angst.

On the other hand, I can understand Loudon’s desire to expand his audience — he certainly deserves exposure — and these new songs are clever as ever verbally, as well as being a good deal more accessible than his earlier work. “Dead Skunk,” “East Indian Princess,” and Leiber-Stoller’s “Smokey Joe’s Cafe” strike me as vehicles for Loudon’s lighter, detached, ‘commercial’ side, and they’re much more effective live, with the added visual element, than they are on record. With the several good, introspective songs Loudon’s had in his pocket for months, often performed but as yet unrecorded, it’s curious that he would choose this fluff instead. These three songs represent the shallow end of the record, and they expose a few potential stylistic flaws: Loudon’s witticisms, when they aren’t used to reveal something about the writer or his subjects, make him seem aloof and strangely cold. When he’s not using his idiosyncrasies (the precise enunciation, the quavers and shrill cries) to this end, the sense of self-parody overwhelms the suggestion of emotional tension, and the whiney nasality of Wainwright’s voice is no longer affecting, it’s downright irritating.

At the other extreme are the three selfportraits included here, “Needless to Say,” “New Paint” (as opposed to the traditional “Old Paint,” a fine rendition of which appears on Album II), and “Red Guitar.” The former has an overtly dramatic violin/cello/french horn arrangement, while the other two are done in the old way, with just Loudon’s voice and guitar. These songs are as good as anything Wainwright’s done; they save the album, since the six songs between the two extremes are several cuts below this artist’s best.

Album III demonstrates that even the most creative people have slumps sometimes. The best ones usually manage to pull out of their skids, and this guy is one of them. He’ll probably create that great work someday, but this isn’t it.

Bud Scoppa

SLADE ALIVE (Polydor)

You guys in Detroit think YOU’RE cool? Then how come you ain’t had no “Slade Fever” yet? The East Coast (NYC in particular) is in turmoil. Not since Mario Procaccinno and when the new pizza place opened up on Burke Avenue has it been so crazy. Fucking is up 62%. Tripping is up 81%. Reading is down 21%. English is down 0.627%. Pants are down 62%. Comic books are up 31%. Sandwiches weigh over 2.4 pounds and contain in addition to your favorite cold cuts: ice cream, mustard, mayo, relish, cole slaw, lettuce, chocolate, tomato, Richard Meltzer, onions, page 23 of the World Book and ketchup.

Edmund Muskie calls it album of the year. Adny Shemoff of Teenage Wasteland Gazette says, “It’s a White Castle hamburger.” Joe Franklin says, “They’re a good band and they serve Hoffman’s Soda.” And from the Daily News, Tuesday, June 16, 1972, the Editor says, and I quote: “Make mine Slade.”

Now, you must agree that any album, let alone an English import (The album is out in the States. Let’s keep the facts straight here! — Ed.), that can cause such a reaction is no English Muffin. Side one opens up with a good song I bet. And that closing number! It’s probably great! They do an encore? Fantastic I’m sure. So I never heard it. I already decided I like it. It’s a great album. Buy it.

R. Evan Cirkiel

This folks, is one wooly record. Slade are a loud, crashing, violent, gross British band who may not be trying to sell themselves as skinheads anymore but still like to do a little stomping now and then. They’re loose enough that they don’t particularly care what the vehicle is as long as it gets them there. TYA’s “Hear Me Callin’,” Steppenwolf s “Bom to Be Wild,” even John Sebastian’s “Darlin’ Be Home Soon” (complete with loudly miked burp in the middle section) — all fit in perfectly with Slade’s rousingly mean-spirited originals like “Know Who You Are.”

On the other hand, I don’t really think it’s as good as I’ve made it sound. Slade fever is a real enough phenomenon in England, with incipient irritations already spotted over here. Maybe it’s just a backlash from the sour taste left by recent hypes like T. Rex and Todd Rundgren, but Slade are already starting to bug me just a wee bit. Some of my friends are talking about this album like it’s the definitive heavy metal monster for the Seventies, when it seems to me that the fever is all more reflective of the current desperation in the audience than anything truly electrifying about the music itself. Buy it yourself and decide.

J. Profumo

FAMILY Bandstand (United Artists)

It’s whoopee time again for the scattered Family fans, what with a new album and a rare two-month tour. Catch them live, if you can — even if you’re as much of a fool for them as I am, you may not like the record as much. It’s not a bad record in any way; it’s just that there seems to have been an effort at musical redirection to something softer and more accessible. Which means, I’m afraid, that Bandstand is a little derivative, a little hackneyed, a little blah. But that’s in comparison to Music In A Doll's House or Fearless. By itself it’s certainly a good record, but one with too much dead weight to really fly.

At their worst, the songs on Bandstand are so strongly suggestive of other people’s stuff that for once Family’s heretofore unassailable originality is cast into doubt. “Burlesque,” the lead-off song and new single, rocks right out, but it’s riffy and big-beat in a way better handled by Hookfoot or Little Feat. Sort of a Yes-as-drunks effect. Who needs it? The second song is nothing more than Emerson, Lake, and Palmer with good vocals (but it’s as good as anything on ELP’s first album, which can’t be said for any of ELP’s more recent turkeys); and so on through a skimpy filler, an oddly cute Cat Stevens-acoustic number, and a lugubrious “sensitive love song,” with nice guitars and the stupidest strings ever. None of it is unlistenable — an effective second voice here, a pretty lead break there — but where’s the usual Family individuality? The unexpected bass figure, the sudden key change, that slightly weird Whitney-Chapman twist? They are here, and though the quantity is rather limited, the quality is high. “Coronation,” it seems to me, would make a better single than “Burlesque.” The words are great, the music is first-rate, and Chapman’s mellow vocal would fall more easily on the neophyte’s ear than his usual shrieking vibrato. There’s also a Familiarly hard rocker, and one called “Top of the Hill” that’s terrific — good lyrics, possibly the best strings ever, a compelling melody, and a real sense of dramatics. It even honestly builds, the way Roy Orbison songs used to. The best of Bandstand, though, is “Broken Nose,” a loud, truly raunchy item about a run-in with a fierce rich girl: “I like your kind of address/Dig your style of clothes/The day that I stopped loving you/ Was the day you broke my nose.” It hurtles along with a determination that’s pretty hard to ignore, and fades out with everyone playing his ass off — energy without ennui, for a' change.

Family have always been among the most inventively progressive of bands, and in the promo blurb I got with the record, it says that Bandstand “should be the record to bring the people of America to realize that Family are one of the best progressive (in the true sense of the word) groups around.” But the false sense of the word, according to United Artists, is “underpaid and underplayed,” So what they’re talking about is that Yes-style progressiveness: slick, catchy, commercial English rock. Well, Bandstand is certainly more commercial than Fearless, and with luck will indeed turn more people on to the band. And rabid Family fans will buy the record anyway, because the good stuff on it does outweigh the mediocre. But it’ll be fucking deplorable if Family, for the sake of a few ulcerated record-company accountants and a shot at the Cashbox Top 100, lose that exciting, unpredictable edge to their music. Buy the record, but don’t be satisfied with it — it’s not their best.

Gerrit Graham

WEST, BRUCE & LAING Why Dontcha (Columbia)

Leslie West is an obnoxious fatso; Jack Bruce was the worst of the three Creams (note his horrible songwriting and bass lead fill-ins) and made two of the most boring albums in the whole history of rock; and Corky Laing is a non-entity (That’s not what his brother R.D. says. -Ed.). Therefore, you’d assume that when three losers like these got together to make an album it would have to be superficial drivel. Not true.

Certainly it’s an innocuous album (in the sense that most Savoy Brown and Ten Years After albums are innocuous), but that just means you can play it all the way through without having to skip any cuts. It’s heavy, bluesy, chunky music with a thick onion soup sound, and all the typical elements of Mountain and Cream are perfectly intact. In fact, it’s Bruce’s answer to Derek and the Dominoes. It’s about time something like this was released, too. Now that Plywoodoor is repackaging all the Cream stuff and shifting it around into four different records, and now that all the old Cream tapes have been milked dry, the logical route is to dig up an imitation.

That’s exactly what this group is, but that don’t mean there ain’t extra-fine cuts nonetheless. You got “The Doctor,” a fuzzy rough rocker with a driving bass line that’ll really grab your ass. “Pleasure” swirls and loops and dips until you begin thinking you’re in the heart of a maelstrom. I’m particularly fond of “Shake Ma Thing (Rollip Jack)” and “Turn Me Over” because they have that special “Traintime” jump sting. A few cuts sound like Led Zipper, tho, but that’s to be expected.

But the supreme cut is the title song, which has the classic AM potential of “School’s Out,” “All the Young Dudes” and “Do Ya.” It’s non-stop hard rock that you can listen to over and over, like “Sunshine of Your Love,” as it whops you in the guts with the following lines:

Why dontcha get in off the streets Come on over and try out my love seat*

No, this ain’t the answer to the gap left by Cream. The interaction isn’t strong enough for such a comparison. These guys are merely playing the role of the Three Musketeers, defending the screaming/battering brand of rock’n’roll. They’re winking at you through this album, knowing full well that you sense their yearning for the days of Fresh Cream and Climbing. But that’s all cobwebs, arid this is such a powerful album that even its mediocrity deserves your attention. The best thing I’ve heard since Eddie Haskell Sings the Blues.

Robot A. Hull

Upfall Music Corp./Bruce Music

LINDISFARNE Dingly Dell (Elektra)

What we got here is a bunch of conscientious guys who used to be one fine Geordie bar band. They?d even break into original university blues at times or a nifty, eeriemisty exploration of Edgar Allen arcana, “Lady Eleanor.” They put on — they still may do, I haven’t seen it lately — a truly fine, boozy live set. Everyone leaves happy.

But goddamit they musta got religion or something. They’ve certainly acquired a large dose of political science and The Irish Question. That’s hard to escape across the water, but I wish they hadn’t decided they had to live up to their consciences on vinyl.

It’s a noble tendency. There’s some witty sarcasm (I hope) couched in an Irish folk tune frame, “Planton’s Lament,” where the boys plead “Bring down the government / Do it now for love... We can find out how / To walk hand in hand to the Promised Land / If we bring down the government now.” This is followed by a dead-serious and truly compassionate lament for Ireland and our poor old creaky cosmos where “There’s still no need / To make blind children bleed.”

I guess I’ve asked for it. I always bitched that if people couldn’t find anything more meaningful than wop bop a loo bop, a wop bam boom, why bother? Well, here it is, and not much is more meaningful than Ireland and thank God people care and all, but you can’t dance to it. You don’t even want to.

Rod Clements throws in the obligatory playing-in-the-band blues, “Don’t Ask Me,” which you can dance to. It’s nice, too long, rhymes good, and is fine if you don’t listen too closely to the words. And Ray Jackson handles a crisp, quavering harp. He claims he admires Big Walter Horton, and if it’s a long way from Newcastle to the South Side, he’s bridged a lot of ocean.

The rest of the album runs to more. Another folk instrumental. An “I got burned by a chick contiguous to the band” song by lead guitarist Simon Cowe. A tribute to Jacka’s genuinely fine mandolin. And more excursions into inner and outer freedom by Alan Hull, who surely must be the fellow most thoroughly bedeviled by the authorities since Guy Fawkes. Two albums ago he was worried about Judge Lynch in “We Can Swing Together,” and now he’s back in trouble: “I’m sorry for the damage I’ve done / Try to pay it back / But the only crime I ever committed was being court (sic) in the act.” Maybe you can boogie to this — but should you?

It’s a pretty simple album. Musically. Psychologically. Politically. It’s from the heart and it’s from a sincere, open sensitivity. It’s not as much fun as it could be. Now maybe they’ve got it out of their systems, now maybe they can work for consistency and consistently placed highs. Even significant ones, or tender ones, if they must. You shouldn’t dance to Dingly Dell. Even if you could. And where’s that at in the neighborhood bar?

Beth Lester

CHRISTOPHER MILK Some People Will Drink Anything (Warner Brothers)

The rumor you may have heard about all rock critics secretly wanting to be rock and roll stars is absolutely true. They won’t all admit it, but I’ve yet to meet one who hasn’t made the fact perfectly clear in one way or another. One noted critic of my acquaintance (who, out of deference to my spot on the reviews roster shall remain nameless) delights, while reeling under the effect of any type of unlikely alcoholic mix you’d care to imagine, in nothing so much as singing through his entire repertoire of self-penned rock songs at the top of his lungs in a voice matched for beauty only by the sounds of a medieval peasant having his eyes gouged out.

Others, like myself f’rinstance, prefer the less obvious approaches such as drawing all the curtains, turning up the stereo to pain threshold, and strutting insanely in front of a mirror, pretending all the while that a bevy of flustered security guards are straining under the weight of hundreds of screaming urchins all desirous of nothing less than ripping the very vestments from my excruciatingly perspiring body. (Ah, what fools these mortals be.) My one prayer in this regard is, naturally, that I won’t get caught in the middle of my mimicry. But, seeing’s how my fingers were always too gangling for guitar, plus the fact that I couldn’t carry a tune in a Glad bag and get unduly nervous before crowds of six or more people, mimicry is my only satisfactory out. (C’mon, Niester, what about that ESP-Disk album we were gonna make together? — Ed.)

One critic who decided that closet theatrics didn’t make it as far as celebrity-dreams go is John Mendelsohn. Mendelsohn, long one of my favorite critics because of his jaunty style and outrageous humor, has put together a band of his own and is now attempting to conquer the one field so rigorously closed to cohorts of his calling for so long. He has put together a rock band named Christopher Milk. In all truth, I secretly wanted to hate this album. When I found out I was gonna do it for CREEM, I spent the better part of that same day laying out a colossal series of scathing attacks. No good, though. Unfortunately, Mendelsohn and Milk (and we have to think of it in terms of being primarily Mendelsohn’s band) have created one of the best albums of the month.

It seems obvious that any album so completely formulated and hyped by a rock critic will end up being a curious melange of musical styles past and present. Some People Will Eat Anything fits this criterion explicitly. The first cut, “Tiger,” and a second side number entitled “Smart Alex” remind a great deal of Family, both in the complexity of the music and in the resemblance of vocalist Surly Ralph to Family’s Roger Chapman (right down to a few well-placed brays in the latter of the two songs mentioned). Milk’s “The Tough Kids” owes a hell of a lot to the dipsy-doodling antics of the Kinks in their Village Green period. But more than anything else, this album owes a great deal, to Abbey Road.

Surly Ralph, undoubtedly the technical star of the band, has his Abbey Road guitar licks down pat beautifully. Although they tend to sneak in and out of nearly every song on the album* they finally break out conclusively and irrevocably in the last number, “In Search of R. Crumb.” This is a great piece, full of subtle contrasts and textural delights, and miles better than the would-be epic from side one, “The Babyshoes Bittersuite,” which somehow never quite manages to get off the ground. (One problem, of course, in starting off at Abbey Road is that you only get to make one more album and then you split. Maybe Chrissy Milk should give this some thought.)

Of the other songs on the album the one that makes the most impact is the band’s tribute to Goffin-King and Little Eva’s “Locomotion.” The piece works well on two levels, on one hand as a parody-tribute and on the other, it makes it musically as well. Mendelsohn treats the vocals like a kid who has been fed a steady diet of downers since he shambled from the womb, and finishes off with a great mumbling exit reminsicent of the old Standells stuff where the singer used to go on babbling until the rest of the band surged up and drowned him out. All this is set against a solid background treatment that quite does justice to the original, chauvinistic rock consciousness notwithstanding.

Some People Will Drink Anything has spent a great deal of time on the old Garrard of late. Sure, it’s weak in places, but show me a first effort that isn’t. It’s my guess that this album even lived up to John Mendelsohn’s prior expectations, and that’s really going some.

Alan Niester

BLOODROCK Passage (Capitol)

Is there any such place as Bloodrock Nation? Maybe in some 4-D acne-bitten hamlet in southern Indiana there’s a secret cadre of junior high school kids who want to grow up to be Ed Grundy, but in my travels there’s only one thing almost everyone I’ve met agrees on. Be they latter-day wobbly folk heads or scab-armed hepatitics, I’ve never met anyone who admits, to liking Bloodrock.

There’s always been a world of difference between Bloodrock and the other teen-cult bands they’ve been linked with. To throw them in with GFR, Sabbath, or Alice C is not to consider subtleties like concept, sensibility, expression, ability, you name it. Even the audiences are different. Your typical middleAmerican heavy metal eater might look strange, one could even say weird. The people who have been attracted to Bloodrock seem to have a foot and a half in the grave.

Fear not, friends, because even Bloodrock knows that. According to their lavish press kit, “the group was weary of singing about death and taking negative stands. A complete reversal in attitude was desired.” Or, as drummer R. Cobb III says, “We’re not going to do ‘D.O.A.’ ever again.”

In a way, that’s too bad. At least when they were a lousy killer band, they had a culture, no matter how warped, to absorb them. With Passage and a few personnel switches, Bloodrock is technically much improved, which makes them merely competent, with no peer group protection to hide their flaws.

Nevertheless, Passage has some good moments. At first I made the mistake of reading along with the lyric sheet — “they prints it, I reads it.” But since there are so few lyricists these days good enough to be considered mediocre, I figured that to pick on some Texas kids for their clumsy syntax would be like blowing up a worm with a cherry bomb.

“Help Is On the Way” is a stand out, a raunch punk anthem with honest dirt under its fingernails. “The Power” is dense, with vague references to the Nixon—Orwell technoespionage axis. “Thank You, Daniel Ellsberg” is a straight blues which at least shows their hearts are in the right place.

Otherwise, this is pretty bland. “Days and Nights” is to Black Sabbath what Lik-M-Aid is to Kool-Aid: close, but no see-gar. Lost Fame” is generally British with Tull overtones, while “Scotsman” is so blatant a Tull rip-off that Ian Anderson could probably sue.

Passage is probably Bloodrock’s best album. It is unlikely to appeal to many people who don’t like them already. I also question the premise that seems to underlie the entire production. That is, whether a “cheerful” Bloodrock, whose Seconal liberalism makes them the downer Chicago, is enough to aid the lame, halt and brain-fried who burnt out on them in the past.

Wayne Robins

BUDDY GUY AND JUNIOR WELLS PLAY THE BLUES ATCO

'OT 'N' SWEATY CACTUS ATCO

Last month I discovered I like Savoy Brown and went around talking boogie until everybody I live with wanted to kill me; this month I’m so fucked up I decided I like blues again. I realize there’s a limit to how many times you can take the poor schmuck whining how his baby caught the katy and left him a mule to ride (it’s on this Buddy Guy and Junior Wells album in case there isn’t). But I was hit this morning with a flash of ineluctable truth: All them metal heavies like Stooges and Black Sabbath build their songs on two or three notes as identical as the stock riffs of the most lame rib joint bluesman, so if you’re gonna be a connoisseur of hypno-monotony what the hell’s the difference? Except the words and nobody with any sense pays attention to the words anyway.

So the first principle of this new era of Blues As Mere More Punk Rock (Isn’t everything, when you get right down to it? Watch out, James Taylor’ll be next; James Taylor’s a pushover!) is that you’re a ditzel if you take it seriously. Take it with Igor the Invisible and a . few Ludes. Take it with I Dream of Jeannie with the sound turned off. But don’t believe a word of it. Because if you really believe in the brokedown blues you’re ten times as narcissistically maudlin as James Taylor ever thought about being, extenuating circumstances or no extenuating circumstances.

Don’t sweat it though, ’cause you’re home free now. The new Buddy Guy — Junior Wells album enjoys the distinction of being one of the least serious pieces of plastic I ve ever had the pleasure to listen to. The words are so banal you can’t even hear ’em, and it rocks all the way when it’s not gettin’ down in those cosmic 12 bar grooves. Pete Welding is gonna lose all respect for me over this, but just as soon as you hear the guitar solo in the first song, “A Man of Many Words,” you’ll know that Buddy has been listening to Alvin Lee enough to dig when to cram in a few dozen more notes than some old croak from the Delta.

Which is where Cactus comes in. They took the lemming urge to the Delta even farther south, to a real parchman of a pop festival in Puerto Rico, and boogied their asses off. Boogie is just blues speeded up, just like Black Sabbath is just Yardbirds and Led Zep slowed down. I’d rather have my bloOz at 78 than 16, so I’m real happy with this one. It’s Cactus’ best album, even if the only remaining members of the original group are the bassist and drummer. Only some personality cult creep would complain.

The live first side of this set is clean away 1 the best spate of nonstop jumpup getdown utterly without annoying social importance since the “Savoy Brown Boogie” on A Step Further. Even better, in fact, because it never lets up for a second. No slow parts. Side two is studio stuff and Cactus’ best work in that dept, too, though it don’t get the heat to the

meat and the wet through the jet near as fast as side one.

Only drag is I just heard Cactus broke up. But while they lasted, they did as much as anybody to carry on the grand traditions that Buddy and Junior are the last oldline daddies of. And we can take comfort in the obvious fact that there’s at least 10 zillion more where they came from. The days of blues AS blues or social barometer or anything but wing of the monotone mazurka are numbered, but blues as kooze picks up its walkin’ shoes and jags on.

Lester Bangs

HARRY CHAPIN Sniper & Other Love Stories (Elektra)

Every picture tells a story, and this story’s full of pictures. It doesn’t matter how well you can draw, get out those crayons and follow the e-z directions. First, draw a curlyheaded runt standing in a studio (you can just write STUDIO on the wall since microphones are hard to draw at first). Put HARRY on his shirt so you know right away who he is, and put a few tears in his eyes (glazed luminescence will do if you’re working in watercolors) to show that he’s sensitive?. In the next caption, he starts to sing... draw him standing the same as before but this time with his mouth open real wide. Write in lots of big words over his head so you know he ain’t a dummy (be careful not to overuse CARTTLAGENOUS) and surround those words with musical notes so it’s obvious to everybody that what he’s doing is singing. In the next caption, he’s joined by a whole roomful of hip studio musicians. Since these are also hard to draw, you could just surround him with a roomful of tapping feet to show that there are other people there, obviously musicians, and that they really dig the shit out of what he’s doing. There are still tears in his eyes, but he’s tough ... he smiles wryly through it all, and the musicians keep on digging him and tapping their feet. It would help if you drew the toe-tapping caption three or four times with the feet getting slightly larger in each drawing to show the musicians’ growing appreciation of what their main man’s putting down.

The next caption has nothing but flowery writing in it, use your best handwriting style to letter in A FEW WEEKS LATER —. And in the picture directly following that draw YOU YOURSELF standing in a record store; you look puzzled and aren’t really sure what to buy. Put a thought balloon over your head: HAS JOHN MAY ALL GONE SOFT OR AM I JUST DEPRESSED TODAY? You’re troubled over the future of popular music and your hands shake (indicate this with wavering lines around them). In the next picture, Harry Chapin enters the record store and walks up to' you. Draw him just the way you did before, but make him about three feet shorter than you. He still has an idiotic wry grin on his face and is pointing to his new Elektra album, THE SNIPER. Draw all that really quickly because the next caption’s great and you’ll want to start on it right away. You squat down (you didn’t notice you were naked in the first picture, did you?) and take an enormous shit right there on the floor of the record store. Personalize it... if you’re a vegetarian, make it liquid and viscous, running down the floor; if you’re a meat-eater, draw it hard and firm and dry. Then you walk away (preferably into the sunset). The last'caption shows a close up of Harry’s face next to the enormous pile of shit; both have big smiles of empathy on their faces, and tears are running down Harry’s cheeks.

Brian Cullman

ROXY MUSIC (Warner Brothers)

What a buncha kooky weirdo faggoids! What a pack of goofy, tasteless dingbats! What a buncha fucking showoffs! It’s not just that Roxy Music are the latest specimens from the David Bowie/Alice Cooper/Silverhead system; they got bat wings, and they fly, too. One of ’em looks like a human fly, another dude resembles a homy King Leonardo, and another one could pass as a member of Flash Cadillac and the Continental Kids. For cappers, the chick glistening on the cover of their album is spread out, willing to bite, and takes up where Veronica Lake left off.

Passing over the pix to the platter itself, you hear sneering electronic fizzle that sounds like Lol Coxhill, White Witch, David Peel and the Move all playing at the same time. Plus you got exciting titles like “The Bob,” “Ladytron,” and “Remake/Remodel.” Who knows, maybe computers thought up the titles ’cause if it’s anything else this is sheer sci-JB music for robots. I hate to be vicious but this music sounds like it was programmed, then mutilated into chugging mechanical bits and pieces, then glossed over with a heavy coat of varnish. Perhaps it’s tongue-in-cheek, as is most drag rock, but why go to all this elaborate trouble (studio production, beautiful jacket design, expensive make-up jobs, etc.) just for a joke? This may very well be an inkling of what’s significant about this elpee, but I don’t think that’s all.

For instance, consider the impact the synthesizer has su4denly had on pop music. The Who are using it, and Lou Reed, and maybe even the Blue Oyster Cult, and it’s all King Crimson’s fault Nevertheless, it’s here to stay, and groups like the Nice have chalked up a big name because of it. Roxy Music’s essence can be found in the synthesizer. Oh, they use an oboe, too, and they have semiclassical arrangements, but that’s all just baloney camouflage. These guys are androids, and they got all the computerized dodads right at their fingertips.

However, although they’re good for an electronic rock group, their charm wears thin after a couple of listenings. The best thing about the record is the group’s costumes and the album design. It’s so godawful synthetic you might even wanna display it on your coffee table. Roxy Music-maker Brian Ferry (he spells it F-A-I-R-Y, and that’s exactly what he is) prisses around, all the hairstyles were by somebody known as Smile, and they even had enough class to dedicate their debut album to Susie.

Roxy Music — they’re a cute group.

Robot A. Hull

THE ROWAN BROTHERS (Columbia)

This record scares me. It scares me because of the cold calculatedness of its aim, it scares me because it’s a patent shuck and a pile of shit but it’ll sell anyhow, and, perhaps worst of all, it scares me because of what it says about a lot of things. Columbia Records has put well over half a million dollars into the Rowan Brothers, and, after listening to and thinking about the album for a while, perhaps that’s the scariest part of the whole thing.

The music on the album itself isn’t much; facile acoustic stuff without any particular depth or melodic inventiveness with a lot of spacey echo-ey, ethereal effects. In fact, it would be simple to write the Rowans off as a couple of trilling Marin County fags, except...

Except they do something to an audience. It has nothing to do with their music or their stage presence, what little of it they have. What they do is no different from a dozen other acts of their ilk, except they do it better, thanks in large part to their producers.

But what they do, by some means unknown to me, is to project a lifestyle. And some lifestyle it is, too. Vegetarian, disengaged, “spiritual,” and - most importantly -easy. It’s a lifestyle that takes no effort to live, that contains no pain, demands nothing, and returns everything. People get together for the sole purpose of having fun, because fun is all there is. Even death doesn’t matter: “Mama don’t you cry/ Even though your daddy’s gone/ He’ll be waiting in the garden/ Where the seeds of life are sown.” The lifestyle dictates that the universe is a huge illusory Ferris wheel which you can ride forever and never have to pay.

Of course, it’s a lie. A most attractive lie, an insidious lie, maybe, but undeniably a lie. It is a lie that looks most attractive to insecure sixteen-year-olds who dearly wish the pressures they feel would just go away. It is the same kind of lie — adapted to the times, of course — that brought the same kind of sixteen-year-olds to Haight Street in 1967. But that was five years ago — there’s a whole new crop by now.

It’s a beautiful morning on a hickory day Come on people, let’s be on our way. We’ll put on our costumes, bring the music along Come on friends we’ll sing a happy song I will bring the fish and rice, if you will bring the wine There’ll be apple pie, honeybread, melons and cheese All for a grand old time Chorus: Say the secret words Halle, halle, hallelu Say the sacred words Rama Rama gloiy too.

Ah, yes, that’s the way it is, living with the Master Race of Hippies in Stinson Beach. And it is glib, dishonest stuff like that which has made me so pissed off at the Rowan Brothers. Not, mind you, at Chris and Loren themselves. No, they’re just pawns in the hands of some totally unscrupulous Svengali figures who are managing them. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with that, per se. The Beatles’ Svengali pushed the lie that love is all you need; Grand Funk pushed the lie that people getting together was all that was necessary to end the war and the corrupt government.

But neither of those lies is, to my way of thinking, as dangerous as the lie of passivity. No, it is not going to be all right. No, you do have to put out in order to get. Clive Davis knows that, and so, presumably, does Jerry Garcia. But they are pushing on people, in subtle and not-so-subtle ways, the' benefits of passivity and subservience. What the Rowan Brothers and the people behind them are selling isn’t good for music at large, isn’t good for the people who listen to it or their attitudes, and especially isn’t good for my faith in the young people of this country, which faith is already near rock-bottom.

So do an old codger a favor, kids, and don’t buy the Rowan Brothers’ record. And do yourselves a favor and don’t buy what the Rowan Brothers are selling. Because they want you to think that they can sell it, when. in fact they can’t because it’s free. You just have to pay a little more for it than they did, but that’s okay too, because you’ll get to keep it long after the Rowan Brothers have been forgotten.

Ed Ward

PAUL REVERE & THE RAIDERS All Time Greatest Hits (Columbia)

There it was, in the very same summer release .'.that brought us Carlos Santana and Buddy Miles Live!, and which one did Columbia choose to promote as “an important piece of rock history”? You guessed it. But I doubt that it bothered Paul Revere & The Raiders much. They’re used to being ignored and laughed at, and, like the crass bunch of young millionaires they are, probably all went out and bought new cars or comething to take their minds off this heinous injustice.

Yeah, they can take it. It wasn’t even cool to like ’em back when they were big stars, and in those days you could like almost anybody — even the Turtles or Lesley Gore — and nobody’d give you any shit. It took me a long time to realize it, but one day it dawned on me: anybody that universally despised must truly have something special going for them, some quality so unique that even people only marginally interested in rock’n’ roll would find it necessary to castigate them.

Their special quality was an almost morbid commerciality, the feeling you had that if the next big trend was Nazi war chants, there would be Paul & the boys smiling through a bright red swastika on the cover of their latest LP. But honest hype is always preferable to sneaky hype, and never once did they ever ask you to believe that they were anything but five clowns out to get rich in a hurry. Can anyone imagine Raul Revere & The Raiders dedicating their albums, energies, and futures to “the revolution in all its forms” like another group on the Columbia roster? No way.

Yep, honesty was the criteria in our culture and even though it’s 1972 and the ballgame’s over, the results have been posted on the scoreboard for all to see and it looks like Paul Revere & The Raiders have emerged as the true People’s Band, the only one that didn’t betray our confidence or lie to us. .

All of which makes this double-LP reissue of theirs even more significant than it already is. A shrine to plasticity, a matte cover with a glossy record inside, and a hell of an album to boot.

Jesus, even Carlos and Buddy will get up and dance when you put on side one with “Louie, Louie,” “Steppin’ Out,” “Just Like Me,” “Kicks,” and “Hungry,” on it. Then flip it over and dig “Good Thing,” “Ups and Downs,” “Let Me,” and surely one of their greatest production jobs ever and a real audience grabber in their live show, “Him or Me.” Lots more, too, and if they yell “Nostalgia!,” flip ’em the bird and tell ’em you dig rock’n’roll, don’t worry about it man. Buy a boat and put it on an 8-track cartridge machine, find out where David Crosby docks and cruise up next to him at three in the morning with “Steppin’ Out” at full volume. See if you can get him to stand up — it’s rumored that he lays down for two months at a time! Invite friends over and figure out where they stole the riffs from — here’s a few clues to get you started: “Let Me,” from the jazzy part near the end of “MacArthur Park,” “Peace of Mind,” from “Rockin’ Pneumonia,” “Just Like Me,” from every song on the first Kinks’ album, etc. Give ’em all some beer and let ‘em find out why you think Mark Lindsay was absolutely the a-number one singer of his time, with more class, style, and sheer power than anybody since. For christsake, have fun with this albm - it’s the only way you’ll be able to hear it in the spirit it was made!

C’mon now, this is it. Your big chance to leave the bearded bozos on your block behind once and for all. Don’t let it get by you again.

Mark Shipper

TAJ MAHAL Recycling the Blues, & Other Related Stuff (Columbia)

Taj Mahal is one of the most mesmerizing live performers in the entire world of rock, or whatever world he’s in. His capacity to send shivers up a collective spinal column is almost unprecedented, and he does it without a hint of flash, Alice. It’s strange to talk about understatement at a time when almost all of the music anyone could potentially like — from Jethro Tull on up, say — is horribly exaggerated, postured and excessive, but the central advantage of having a name like Taj Mahal is that you can get away without doing anything else outrageous. It’s sort of like the way Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band look so strange you tend to forget about the fact that what they are doing has an internal logic.

Taj’s refined but funky presence is dangerous, in a way, because it does let him fit into a lot of stepinfetchit stereotypes. But that is the observers’ problem, not Taj’s.

Recycling the Blues is probably his best record since the first two, which are both gems. Only the first side really makes it, but jt is strong enough to carry the idea that the whole album is a success. There’s something to be said for the idea that the first side works because it is live I think but that isn’t all there is to it.

Maybe it’s just that his repertoire is limited, in some way, but there’s a sense of familiarity on the first side of Recycling the Blues that is hard to find anywhere. There’s magic in the man, and sometimes it comes out in his music. Taj knows how to rock in terms of a tradition that only he seems capable of properly dusting off and making vital again. If it doesn’t always work, here or elsewhere, and if Taj Mahal sometimes seems as much an anachronism as 'his name, he’s still nothing less than the best acoustic performer around.

Dave Marsh

EGGS OVER EASY Good 'N' Cheap (A&M)

Sometimes it gets downright hard to remain cynical. Witness this latest destined-forobscurity near-masterpiece (produced by Link Wray) from three former Berkeley folkies who pulled out for the Big Apple, thence to England where they turned into ace rock & rollers thanx in part to Chad Chandler.

Make no mistake. Eggs Over Easy is America’s closest answer to Brinsley Schwarz, who were England’s answer to America’s answer to England’s answer to America’s -, and they also have something to do with the longdead Lovin’ Spoonful and legitimate “goodtime music.”

It must have been about 1969 when I stopped listening to Daydream, Hums and Do You Believe In Magic. By then the Spoonful canon of innocent lovesongs and sweet postteen ditties to sunlight, new mowed lawns and jugband music, their humor - all seemed suddenly distant, as if the shadows of “You Didn’t Have To Be So Nice”, “Good Day Sunshine” and the Sopwith Camel peaked with the bright Pop optimism of the ’65-’66 season and would never flicker past us again. Then, I reasoned, Times Had Changed, apocalyptic visions crowded every head, and the light focused on every scene, music included, became a little darker, a shade more resolute and serious.

Times do change, I guess. ’Cause in Good 'N' Cheap there’s a plenitude of good-feeling, good-sounding American rock music once again, and it’s rather delicious. For some idea of the flavor, start with the deja vu jacket; it invites scrutiny if only for its depiction of a scene so oft repeated (comic books, movies, oil illustrations in Esquire and Playboy), so deliberately American in conception and execution, as to have attained legit mythic status years ago. You can’t escape it, or the premise of every square inch of music it packages. Love it or leave it. This is plastic salt & pepper shaker, stainless steel creamer, magenta trim restaurant coffee cup music, short order U.S.A. stuff, no more and no less.

Did they gamer their firm roots vision from that trip to Merry Olde, from hanging out with Link Wray, from California or Ohio or Wisconsin Sixties kidhood? I don’t know, but Austin de Lone’s voice is as arch-stateside as Jackson Browne’s or that guy in Earthquake and it’s the first one you hear, on “Party Party”, a perky tune with a familiar yet untraceable ring. “The Factory” comes on strutting a little J.Geils/Contours spunk with de Lone’s dandy phrasing and somebody’s (his, or Jack O’Hara’s) quick cut guitar. On the soft side, “Song Is Bom of Riff And Tongue” sports a readymade ‘Spanish’ melody lilt and a vocal that eases into territory somewhere between Art Garfunkel and Little Feat’s Lowell George, silvertone ether pretty.

They’ve got a solid synthetic aesthetic too, Eggs. “Don’t Let Nobody” and the great “Henry Morgan” prime themselves on bass figures on loan from the Soul Survivors and the Capitols (“Cool Jerk”), and yet, with “Runnin’ Down To Memphis”, display equal affection for Floyd Cramer pianistics.

And the best comes last: “Night Flight”, a taut rocker with lines strung to both C. Berry and Grand Funk’s “Upsetter” that finds the whole band sounding their strongest and noticeably digging every second. Perfectly placed, simple guitar frames the song around the same kind of full chord flame that made Link Wray’s recent “God Out West” such a mover.

When groups like this show up with records like this one, it’s casino odds that something’s in the air. It’s almost enough to push those apocalyptic visions right outa your head, for awhile at least.

Gene Sculatti

JOE LAUER AND THE CRAZY GANG Everything You Always Wanted to Know About the Godfather But Don't Ask (Columbia)

So we get dis contrac from da Godfaddah to put da squeeze on dat Chinese laundry on 42nd st. and wuddya know it, Watery Grave DeBartolo lost da address of da joint dat was written specially for him, and den directed Peanuts Envy Scopoli to shoot up da kosher pickle place next door. Boy I tell you, when da Godfaddah heard about dat, he was SO pissed! Now how was I to know dat da Godfaddah was mad about kosher pickles? He likes to eat dem wid his Veal Parmesan and Volpollicella.

Well, any rate, when we entered da Godfaddah’s office, we waz naturally a little, you know, apprehensive about how he was goin to receive us, but he jus stood dere, wid his back to us an’ just gazin out dat window. So Peanuts, dat lunkhead, sat down in dat big leather chair in da middle of da room, and da cushion on da chair let out dis high pitched squeek which sounded real loud in da silence. And den da Godfaddah turned real fast like and said, “Dat’s da sound of a squeeler! I’m tellin you kneeandertalls dat whenever you hear da sound of a squeeler, you shoot first, and den dump da remains into da East river.”

Well naturally, dat got ol’ Peanuts all shook up. But den da Godfaddah smiled a little smile, and deh reached over to dis polished wood box on his desk, opened it, and said:

“Kosher pickle, anybpdy?”

We just shook our heads no, except for Watery Grave, who took one, bit off da end, and den lit it. Well, you can iipagine da look on his face — and coat, shirt and tie — when it blew up just as he was standin dere. And den da Godfaddah said to us, while he was eatin his kosher pickle:

“Now look here, you morons! When I give you a job to do, I expect you to do it. Now, I know dat dere aint much difference tween a Chinese laundry and a kosher pickle place, but to blow up a kosher pickle place just aint yiddish. But, just because I’m a nice guy, an I tink dat you tree boys deserve another chance, I’m goin to give you another job to do.”

Peanuts Envy, Watery Grave and I all perked up our ears and listened close to dis. What was he goin to have us do?

“Boys, you all know dat dere has been a lot of unfavorable publicity about us lately because of dat movie dats so popular. Well, now we got to lean on da president of Columbia records, for puttin out a dumbino comedy album dat ribs all us loyal Americans of Italian blood. Da record is called Everything You Always Wanted To Know About The Godfather* But Don’t Ask, and boy is it stupid! Now I want you to rub out that guy Clive Davis and not just because of dat album, but also because of da name of his company. Columbia. Now dat’s just a blatant insult for a fine Italian boy whom we all know about, Christopher Columbus, who discovered dis fine country, and was also a direct ancester of me personally. Now you boys go and show dat bastard what for, and L’ll personally do any favor you wish of me.”

“Sure, Godfaddah,” I said, “But what happens if we aren’t able to get him?”

“In dat case,” said da Godfaddah, “I will force you to listen to Dean Martin records for ten hours straight.”

Well, da next ting we knew, we was on our way to Los Angeles to do da job. One ting about da Godfaddah, he sure knows how to put da scare into his men.

Rob Houghton

KREAG CAFFEY (Dacca)

Dylan’s back and I sure am glad. It was like a fresh breath of new morning today as I heard that good ol’ nasal whine and those absurd lyrics and sloppy harp on the car box as I was truckin’ over the good ol’ Bay bridge and thinkin’ about the good ol’ days. Or something.

Oh, Bob’s clever. Foxy. He’s changed his name again (he knows that “Dylan” business didn’t fool us for One Minute, not like we were fooled for a little while there when our brains got all scrambled somehow. As Grace was telling me last night over java at the Doggy Diner, “I sure as shit ain’t gonna get fooled again, Jack.” Crazy Gracie. Trust her to come up with the bon mot, as Satch used to say when he and I would prowl the angry Arab streets of Paris in the gray Gallo morning. “The kids are alright,” I would reply and Satch would roll growling in the gutter at my quip. Satch knew. “The only thing wrong witchoo,” he would finally gasp, “is that you don’t know yer ass from a closed parenthesis.”).

But Bob’s changed his name again (it may take me a couple of years to think through this change but I’ll tell you when I do) and he’s living in LA (that substanceless scumbag of a “city”) and going by this here monicker of “Kreag Caffey.” It’s Bobby’s most brilliant ploy thus far. Who would ever expect The Man (and he is The Man, to quote one of my legendary columns) to cut in LA under a goofy name like this? But it is Bob, we can all rest assured and just be thankful that he’s showered us with 42:23 of his sacred wisdom and cosmic gifts. (I have decided that the era which begins with this historic release shall henceforth be known as the “Age of Enlightenment.”) But it is Bob. Why, just listen to that scrawny voice and ragged harp:

her doll cry eyes pour tears from their sockets last year’s queen, die’s out for the good time. She keeps your needs quite safe in her pockets, she’s the lady love, she’s a bleak dream taker with a sense of crime.

(Copyright 1972 Golden Trout Music)

See, that’s Bob’s sweeping, awe-inspiring restatement of “Just Like A Woman” mingled with the lesson of “Like A Rolling Stone.” In a word: Restoration Row. Yeah, it’s Bob. Looky here, words about landlords and lamposts and keepers and winds blowing. And more of his unique rhyming: shook, look, book, took. What do you suppose Weberman’ll make of that, huh?

Now Bob’s back as our signpost and with his help we can think through all these heavy changes (Memphis State! Altamira! Woodbury! Dylan showed us the way out of those nasty mental cul-de-sacs, as it were, and don’t think we ain’t grateful neither, Bob, ’cause we sure are. I myself may be moved to nominate you for Comeback of the Year.)

Oh, Sweet Jesus, I’m excited! I just played the album again and am just discovering the secret meanings and sudden turns and flights: “Love Minus Zero,” fr’instance, has evolved to “Sweet Zero.” Are you ready for that, you got eyes for that, can you handle it?

And the sound! Bobby’s wisely gone back to the Blonde on Blonde type of music and his voice has changed a little now that he’s more mature and smokes cigars. I suspect that some of The Band is backing him up under assumed names, ’cause Bob mentions “The Weight” in one of his new songs. Clever? Yewbet.

So we can all sleep a little easier tonight. Dylan rules again and all’s right with the world.

(Wait a minute, wait just a fucking minute! What is this, some kinda joke? Jerry — you know and love Jerry — just came in and said he had heard from Boz that Donovan’s just changed his name to Kreag Caffey. Very funny, Jerry. Just for that, my next column’ll be about good ol’ Carlos. And Marty — my old friend Marty just called from Nashville and said that Leonard Cohen had changed his name to Kreag Caffey. That’s not at all funny, Marty. Wait’ll I tell Grace on you. And Robbie — remember him? — he called to say that Paul Simon had changed his name to ... OK, epough is enough. Fun’s fun, but this shit’s gotta stop. I can take a joke but not at the expense of a gifted and sensitive genius. Bob’s Back. That’s all that matters.)

Chet Flippo