Features

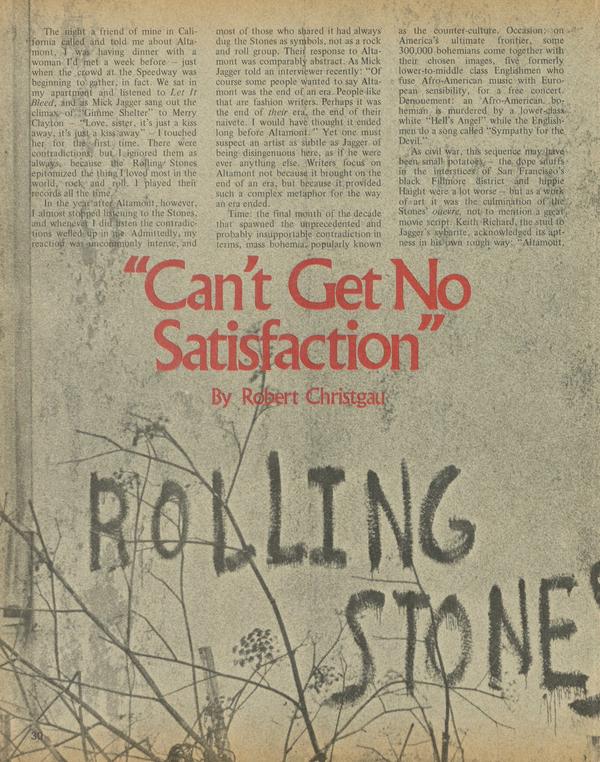

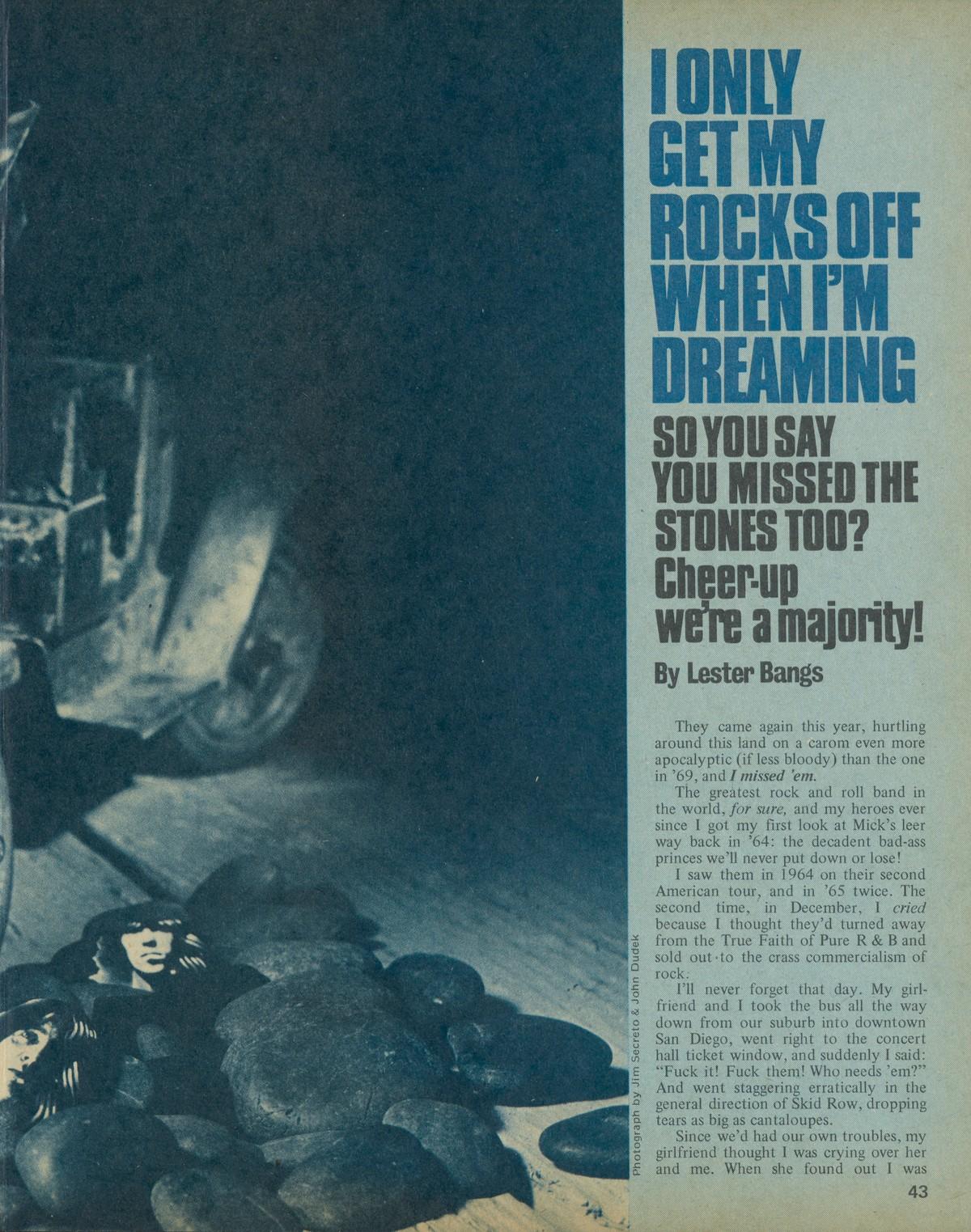

I ONLY GET MY ROCKS OFF WHEN I’M DREAMING

So you say you missed the Stones, too? Cheer-up we’re a majority!

The CREEM Archive presents the magazine as originally created. Digital text has been scanned from its original print format and may contain formatting quirks and inconsistencies.

They came again this year, hurtling around this land on a carom even more apocalyptic (if less bloody) than the one in ’69, and I missed ’em.

The greatest rock and roll band in the world, for sure, and my heroes ever since I got my first look at Mick’s leer way back in ’64: the decadent bad-ass princes we’ll never put down or lose!

I saw them in 1964 on their second American tour, and in ’65 twice. The second time, in December, I cried because I thought they’d turned away from the True Faith of Pure R & B and sold out-to the crass commercialism of rock.

I’ll never forget that day. My girlfriend and I took the bus all the way down from our suburb into downtown San Diego, went right to the concert hall ticket window, and suddenly I said: “Fuck it! Fuck then*! Who needs ’em?” And went staggering erratically in the general direction of Skid Row, dropping tears as big as cantaloupes.

§| Since we’d had our own troubles, my girlfriend thought 1 was crying over her apd me. When she found out I was crying for the Stones you better believe she was pleased as puke!

“You’re so immature!” she said. “Here I thought this was all because you loved me, when it’s really because you’re mad at the goddamned Rolling Stones.”

Damn straight I was! After four fantastic albums of the purest R & B (like “Off the Hook”), they’d let me down mucho queaso with the release in close succession of “Get Off Of My Cloud” — which even Mick Jagger later called “just a bunch of noise” (I love it now, of course, and could give a flying fuck what he thinks) and December’s Children, their worst album to date. It had several songs on it that sounded about half-completed, as well as the insipid “As Tears Go By” (yeah, I get the hots for that piece of crap now, too, of course. D.C. ditto.) Even Andrew Loog Oldham’s all-time worst liner notes.

But the day of the concert found all my blustering disdain drained to sheer distilled sorrow. A fan in mourning! Oh Stones, Stones, how could you do this to me? Andy and I walked downtown a ways, a little bitty tear letting me down every so often. Finally we stopped into a little Coney Island hotdog trough. We ordered. I glumly flipped the pages of the jukebox, put in a coin and played “Get Off Of My Cloud.”

Man, those tears started pouring out like piss from an elephant! The farther the Stones got into the song, the more distraught I became. Stop breaking down!

Suddenly, Andy was up, resolute, yanking me out of my seat and through the door, literally tugging me back into the concert, running as fast as she could with a big imbecile in tow, blubbering and falling all over himself.

When we got there, she snatched my wallet out of my pocket, threw the money at the ticket seller and yanked me inside. We found our seats, I wiped my eyes and cheeks on my soggy sleeve, and THOSE MOTHERFUCKERS PLAYED ONE OF THE MOST EXCITING CONCERTS I’VE EVER SEEN IN MY LIFE! Rejuvenation!

It was almost as good as the night earlier that year when I’d sat there in the same half-filled theatre, shrieking in harmony with all those wet-pantied little hoppers. I was a groupie! Still am, in a way. Every time I’ve seen the Stones, or missed them, every time they’ve come over here or released a new album or even just made a bit of news like pissing on gas stations or going to jail for dope, it’s made waves in my own life.

Exile on Main Street came out just three months ago, and I practically gave myself an ulcer and hemorrhoids, too, trying to find some way to like it. Finally I just gave up, wrote a review that was almost a total pan, and tried to forget about the whole thing. A couple weeks later, I went back to California, got a copy just to see if it might’ve gotten better, and it knocked me out of my chair. Now I think it’s possibly one of the best Stones albums ever.

Meanwhile, what with travelling and general sloth, I somehow missed seeing any of their concerts on this tour, and for some reason even the full bloom of my love for the album couldn’t make me care that much.

What was responsible for my dra^ matic turnaround on the album? I don’t think it matters much. Why don’t I care that much whether I get to see the Stones live this time? That’s another story altogether. It’s directly related, I think, to the difference between what you find in the album if you listen, and what you couldn’t help but see operating on this tour.

The Stones still have the strength to make you feel that both we and they are hemmed in and torn by similar walls, frustrations and tragedies. That’s the breakthrough of Exile On Main Street.

Exile is dense enough to be compulsive: hard to hear, at first, the precision and fury behind the murk ensure that you’ll come back, hearing more with each playing. What you hear sooner or later is two things: an intuition for non-stop getdown perhaps unmatched since Rolling Stones Now, and a strange kind of humility and love emerging from the dazed frenzy. If, as they assert, they’re soul survivors, they certainly know what you can lose by surviving. As they and we see friends falling all around us, only the Stones have cut the callousness of ’72 to say with something beyond narcissistic sentiment what words remain for those slipping away.

Exiles is about casualties, and partying in the face of them. The party is obvious. The casualties are inevitable.

Sticky Fingers was the flashy, dishonest picture of a multitude of slow deaths. But it’s the search for alternatives, something to do (something worthwhile, even) that unites us with the Stones, continuously.

They are masters without peer at rendering the boredom and desperation of living comfortably in this society. If you recognized yourself watching the last TV station sign off at 3 A. M. in “What To Do,” chances are you reveled in the rich, sick ennui of “Dead Flowers,” and saw your own partial fragmentation between the sonic icefloes of “Sway”:

Did you ever wake up to find A day that broke up your mind . .. Can’t stand the feelin’ gettin’ so brought down.

Most of us didn’t get the real words, because at their most vulnerably crucial moments they were slurred and buried in the tides of sound. Jagger had to sing it that way, in “Sway” and much of Exile, because that is the way his pride' works. Besides, anything else would make it all too concise and too clear — like putting the lyrics on an album cover, which is the most impersonal thing any rock’n’roll artist can possibly do.

Exile On Main Street is the great step forward, an amplification of the tough insights of “Gimme Shelter” and “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” A brilliant projection of the nerve-torn nights that follow all the arrogant celebrations of self-demolition, a work of love and fear and humanity. Even such a piece of seeming filler as “Casino Boogie” reveals itself, once the words come through, to be a picture of life at the terminal:

Little girl can’t speak Wound up, no sleep Sky Diver inside her Slip rope stunt flyer Wounded lover got no time offhand Burnt out cycle, red freak in the sand All forbidden, know you understand Judge and jury walked out hand in hand.

“Rocks Off’ and “Shine A Light” present the essential pictufe, the latter song addressing the half-phased out but still desperately alive person who speaks in the first. This music has a capacity to chill where “Dead Flowers” and “Sway” tended to come off as shallow, facile nihilism:

I always hear those voices on the street I want to shout

but I can hardly speak

I was makin’ love this time To a dancer friend of mine. I can’t seem to stay in step... And I only get my rocks off when I’m dreamin’

Headin’ for the overload Stranded on a dirty road Kick me like you kicked before I can’t even feel the pain no more.

The sense of helplessness and impotence is not particularly pleasant, but this is the way it is today for too many. Such withering personal honesty is certainly a departure for the Stones.

“Kick me like you kicked before . ..”: the Stones talking to their audience, the audience talking back. Old lovers who may have missed the bourgeois traps of “Sittin’ On A Fence” but got waylaid anyway by various disjunctures; they certainly don’t yearn like saps to get back to where they “once belonged, but they do recognize the loss of all sense of wonder, the absence of love, the staleness and sometimes frightening inhumanity of this “new” culture. The need for new priorities.

When sq many are working so hard at solipsism, the Stones define the unhealthy state, cop to how far they are mired in it, and rail at the breakdown with the weapons at their disposal: noise, anger, utter frankness. It’s what we’ve always loved them for. And it took a lot more guts to cut this than “Street Fightin’ Man,” say, even though the impulse is similar: an intense yearning to merge coupled with the realization that to truly merge may be only to submerge once more. A recognition that joining together with the band is merely massing solitudes.

The end of the line and depths of despair are reached in “Shine A Light,” a visit to one or every one of the friends you finally know is not gonna pull through. A love song of a far different kind:

I saw you stretched out in room 1009 With a smile on your face and a tear right in your eye Oh, I come to see, to get a line on you My sweet honey love ...

When you’re drunk in the alley baby With your clothes all torn And your late night friends all leave you In the cold grey dawn Oh, the Scene threw so many flies on you I just can’t brush ’em off...

When Mick says he can’t brush off the flies, it’s not some bit of macho misogyny, but a simple admission that applies to himself as well. The sense of entropy, of eclipse, is as total and engulfing as the sorrow. “Soul Survivor.” follows immediately, of necessity, carrying the album out strong and fierce because the Rolling Stones are about nothing if not struggle. They have finally met the Seventies totally.

What Exile on Main Street is about, past the party roar, is absorption. Inclusion. Or rather, the recognition of exclusion coupled with the yearning for inclusion: “Yes, I’m stumbling/And I know I play a bad guitar/Let me in! I just wanna drink/From your lovin’ cup.” When I saw them for the first time in 1964, a friend turned to me and said, “The great thing about the Stones is that the Beatles are so distant and perfect you feel like they’re from another planet. But with the Stones, you feel like you’re at home.” And it is still true, except in a much more profound way.

If Exile on Main Street is about the need for inclusion, the latest Stones tour is about the tactics of exclusion. If the album cries out for the reciprocal resolution of tension, the tour runs on crackling rails of tension, frustration, disappointment and envy. It may not have been planned that way, but that’s how it works out.

The entire project looks to a moderately jaundiced eye (what other kind is there with the Stones?) like an exercise in manipulation at the highest level. If “Rocks Off’ asks for a recharge from the street, this tour has been designed to leave you stranded on a dirty road.

Consider the fact that the Stones consciously and carefully chose to do their 32 stop tour in a series of concert houses generally smaller than those of 1969, with audiences systematically limited. At every stop, only a certain percentage of those who want to will be able to see the Stones. Never enough tickets; they’re always gone in no time. Standing in the sun for hours until the man finally comes out and announces that this one’s sold out, too. Tough luck kid. But, if you’re really rich, maybe you can find a scalper.

These conditions, combined with the police and security measures which have been fantastically (and understandably) elaborate, have not set well with the underground press or the hip community at large — one paper in the UPS chain after another has run denunciations of the Stones as mercenary pigs, usually alongside a piece of equivalent length rhapsodizing over the show and music themselves, as well as overloads of photos. Some of the accusations have validity, and some are freelance paranoias, but certain facts must be considered and certain questions asked.

Why did the Stones and their organization chose to limit so severely the audience at every show on the tour?

Possible answers:

* Afraid of another Altamont, they wanted to prevent tragedy, as well as reduce the likelihood of personal harm to themselves. The Rolling Stones have a lot of enemies in America, whose faces they have never seen: in the New Left, women’s liberation, people who still nurse real or imagined grievances over the last tour (including bikers, who felt that they had been roundly shafted on Altamont) as well as various cranks, ODS, Bremers, etc. Just say the Stones never quite understood everything involved in the Altamont flashpoint, and went out of their way to ensure that on this tour nothing but a good time would be had by all lucky enough to get inside.

* The Stones recognized that neither audience nor band gets off properly in vast arenas due to the impersonality, as well as hugely erratic acoustics; so they sacrificed the really big money in favor of relatively small environments where a certain intimacy could cook between audience and band, resulting in better music, more satisfied customers, increased relaxation, better vibes all around.

* The Stones knew that if they consistently limited the number of people who could see them, a huge tension would be set up which would add to the excitement, the sense of a momentous historic occasion. The external hysteria in each city might, by this stratagem, be simultaneously stroked and tethered short of total chaos. The Stones could barnstorm the colonies, make a certain percentage of their fans happy, capture the attention of a drooling press resulting in cover stories everywhere, sell out every house, make history, stay in the news, keep everybody in America in a state of anxiety till they left, enjoy a manageable apocalypse with no bummers or miscarriages, come off as simultaneously the last word in outrage (like Life clucking over the illegitimate children in their collective wake) and good, professional guys (nobody died).

The first two answers make pragmatic sense but the last sounds so much like Mick Jagger it’s all but irresistable. Most likely, it was a combination of all three. Even the third does not seem a total act of manipulation. The distance between intentions and effects is often so vast in matters of this kind that you could almost (but not quite) easy ride with a creep like Jerry Garcia babbling about how there are no bad people, only victims.

Take Altamont. It was great! I was really glad I went — no question of preferring that experience to Woodstock, which I missed. But, I remember thinking all day, “If I was waiting to see anybody but the Stones, I’d leave this fucking shitheap right now.” I remember the naked sobbing girl who came stumbling down past us, shoved by some irate redded-out boyfriend up the hill, everyone ogling her and snickering, and her attempts to cover herself as she dazedly picked her way back io her friends, stumbling as she stepped uncertainly through the tribal circles of beatified freaks who dug it all laughing and grabbing. And I remember the freaked out kid shrieking “Kill! Kill! Kill!” I remember the Angels vamping on him, too, and then seeing him passed in a twitching gel over the heads in the first few rows and then dumped on the ground to snivel at the feet of total strangers who would ignore him, because the Stones were coming on in a minute which would be two hours. But nobody wanted to take their eyes off the stage for fear of missing them.

I don’t think the Stopes saw much of this. If they did, what could they'do? Call it off? Call out their bodyguards? Call the police? But the Stones are not innocents. As successful as the tour just ended was in avoiding Altamont II, it’s not all instant party. It doesn’t even stop at money, power and ego, as Ralph J. Gleason said, although that’s a third of it. Another third is rock’n’roll.

The other third is law’n’order.

The incredible degree to which security was enforced on this year’s tour was justified — mostly — by equally incredible circumstances. But there are always casualties, not to mention simple injustices. In San Diego, for instance, some hip con made up several hundred fake tickets and sold them. As a result several hundred people with legitimate ones found themselves stranded outside the arena. With no recourse but to, quite appropriately, rip the joint to rubble. Wouldn’t you? Or wish you could, if you didn’t have the guts? Where does “drive myself right over the wall” stop? Should it? I don’t know.

The most interesting form of security on this tour, though, was that phalanx of mostly non-uniformed bodies which kept the Stones permanently insulated.

A diagram of that insulation can be found on pages 48 and 49.

Right. Concentric circles. Just like Dante, if a trifle more sleazy and less important. The Stones are a target for every parasite alive. So they and the parasites end up with:

* The Stones. Eye of the hurricane.

* Their entourage. Family friends, occasional acolytes and musicians not in The Stones. You don’t think Bobby Keys rates with Charlie Watts, do you?

* Roadies, technicians, businessmen, PR people. (They get to hobnob with the Stones, though perhaps not so much as the inner circle.)

* Members of the press travelling with the Stones. These people get to see a lot of the band — sometimes more than the friends, sometimes less than the drones. Anyway, they garner plenty of anecdotes and style notes, even though most of their articles are elegant press releases.

* One nighters. Media people in each city with backstage passes, who get to interview or photograph the Stones or just stand around.

* Media people and assorted rock scene hustlers who got in free, courtesy of PR, but with no backstage passes. They get to sit out front, which is reasonable. There’s always too many people backstage.

* Next, of course, the paying audience. Used to be that included everybody who gave a shit in the first place. On the first few tours, nobody was excluded, because the Stones didn’t fill the house that often. By 1969, everybody knew; part of the excitement was that the next day or in the wee hours after the concert you’d reconnoiter with your friends to bask in the memories. It may seem petty, but it was important: “Geez, weren’t they fabulous!”

If you can say that now, you’re a member of an elite. Chances are two out of three Stones fans missed ’em in ’72, which puts you outside the eighth circle, in the great circle with no boundaries:

EVERYBODY ELSE

There is no way this cannot sound like sour grapes, but it really isn’t. A tour of this size is an undertaking on a scale with building the pyramids. One could even say that it’s not all champagne and rockin’ glory for the Stones either. A friend who travelled with them told me that they were consistently surrounded by people of an extremely low calibre. Low in many ways, he said: mean, unhealthy, alternately hostile or sycophantic (depending on who they were dealing with), burnt out, tattered, unpleasant to look at and be around. The Stones’ patience with them, he added, was unbelievable.

Then again, I don’t see many rock’n’ roll bands at gigs with people around them that I could admire or care to exchange two words with. Burnt out cycle. The Stones are professional artists and businessmen, doing a job, giving something for all they receive.

But it’s also true that this tour probably made as many people unhappy as it R made happy. There’s a line in “Torn and Frayed” about “impressive rooms filled with parasites.” While it’s true that almost nobody gets to hobnob with the Stones that the band don’t want to look at, it’s also true that when you’re in the kind of elevated (what?) position the Stones are in, people keep relating to you in the most peculiar ways. Nobody wants to look too eager. Meanwhile, you’re travelling fast over enormous distances, losing track of day and town and when you last slept. I imagine it must get kind of hard after awhile to bring most of the hangers-on into focus. If you did, who knows but what they might turn out to be a pain in the ass.

I guess I just feel that circumstances effectively disrupted that certain aura of spiritual intimacy represented by the comment of my friend at the ’64 concert, and even meeting friends after ’69 shows. The Stones were with us even after we went home. I don’t feel snubbed because Mick Jagger didn’t call me up the minute he hit America, to thank me for my Exile review.

It’s just that even though I don’t exactly have any illusions to be destroyed anymore — even illusions about the Stones being inhuman rrianipulators with evil ends — I’m happy with what illusions I do have. You probably are, too.

So this piece is dedicated to all the people who didn’t see the Stones this time, from one who excluded himself for no particular reason, but wouldn’t worry too much about being excluded anyway.