Records

APPOMATTOX REDUX

The Allman Brothers have one very serious, probably insoluble problem: they want to die.

The CREEM Archive presents the magazine as originally created. Digital text has been scanned from its original print format and may contain formatting quirks and inconsistencies.

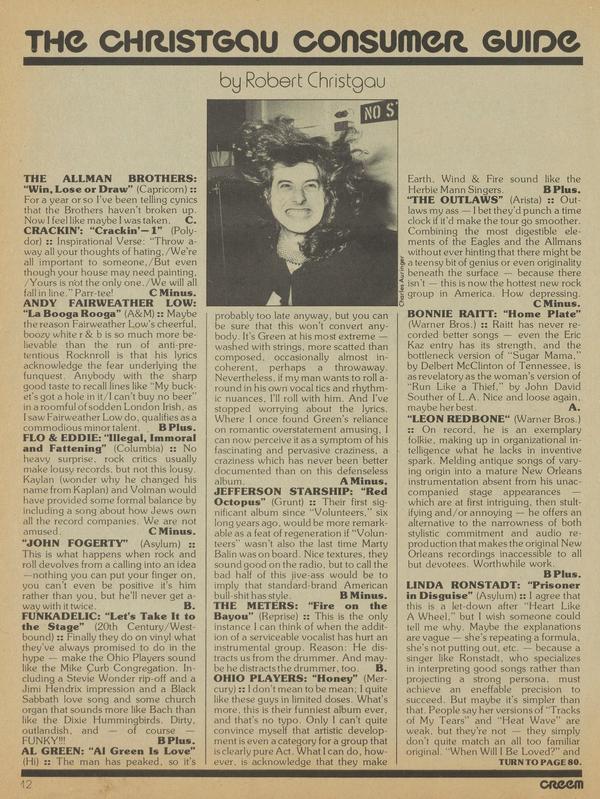

THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND Win, Lose or Draw (Capricorn)

The Allman Brothers have one very serious, probably insoluble problem: they want to die. Not physically, necessarily, but as a collective force in the world at large they long to tumble back into that warm Confederate loam and rot gloriously away, dreaming of crumbling dynasties as the twilight slowly descends on Appomattox.

It’s sick, all right, but there is no geographic state of mind more literally decadent than the American South. And 1 exclude from that untold millions of people who live there — I mean the romantic lames who believe in Raintree County, Gone With the Wind, and the more extravagant folklore of Tennessee Williams and Erskine Caldwell. White Southerners who get their kicks off that fantasy are no different than black people who shuffle and play dumb nigger; they have merely projected their own spinelessness on the rest of their countrymen.

Which is where the Allmans and this album come in. It’s interesting that what will almost certainly be the Allmans’ last studio album is a concept number about gambling —almost every song deals with chances taken and lost, and the clear inference seems to be that the Allman Brothers fought a long hard dusty road, lawd, but death and trouble got in the way so this is their last fair deal gone down. Except that it isn’t a fair deal at all. No band is dealing off the top that wastes almost half of their first new album in two years on a boring instrumental jam that’s almost exactly similar in construction to the instrumental on their last record, except that it’s over twice as long and about a third as inspired.

What’s truly tragic is that in cashing in their chips at this point the Allmans have left us desperately lacking any authentically badass American bands; they may be the last of a vanishing breed. You can still hear a little bit of their hoodoo in this album, even if most of it does sound sodden and gutless. In Muddy Waters’ “Can’t Lose What You Never Had,” the only really good track here, the guitars slide low, dirty and mean as diamondbacks in the hot dust, and for this cut at least they bite to kill. The singing here is also rough, gritty, convincingly angry enough that it pushes on through the natural defeatism that’s part of the blues to a pissed-off seethe that more than does justice to the original bloodlust saga. The guy in this song isn’t just wallowing in the post-bellum moonshine while the moss rots on him — if he has to kill the bitch and her pimpbdytoo, he’s gonna see that he extracts-justice. Or at least his own satisfaction.

But the Allmans don’t want satisfaction. They want to luxuriate in a tarbog of self-pity and motorcycle legend. One of their main mistakes is that they’ve confused romantic defeatism with the tribulations of the real blues experience, which was always tinged with defiance. They took “Live fast, love hard, die young” literally; hell, they probably feel guilty they didn’t go down in that same spot. They should have “Born to Lose” tattooed on their picking hands.

I’m not saying they were always this way. The Allman Brothers Band used to have that raw, rangy quality, like leather straps stretching taut and snapping back, like warm Gulf Stream waters flowing deep and fast and always hitting you with the rip tide exactly when you needed it, sweeping you right out of your boots and off in Duane’s torrents. They were a true defiant outlaw pack back then, and their music was for tearing the asphalt off the highways in your car, roaring through endless nights of bottomless jugs, hooting and cussing and fucking and fighting and not giving a damn. Hell, it sure beat joining the army.

I didn’t even pay attention to the purists who said they lost it with Duane and Berry. Brothers and Sisters was strong fine American music: bitter “Wasted Words,” “Jessica” clear and fresh as the cold beer we drank to it, waiting for “Pony Boy” to carry us all home. But never thinking his bony knees’d buckle so soon. These boys just ain’t tough anymore, pussies like the rest, and when Bukka White sang “Fixin’ to Die” 1 sure don’t think he was talking about this.

But then, he was a real gambler. Win, Lose or Draw plays no longshots. “Just Another Love Song”: you’re not kidding. How many times has Betts written this melody or almost identical variant? “Blue Sky,” “Ramblin’ Man,” almost everything on his solo album but its long jam. Points of interest: (1) It becomes more apparent all the time that Dicky’s vocal apparatus is so severely limited that he’d do better to take up the musical saw. An adenoidal whine so pathetic it makes Dylan’s Planet Waves voice sound like Paul Rodgers. (2) Why were all the versions of this melody featured on Dicky’s solo album clearly superior, in lyrics as well as vocal and instrumental delivery, to the ones here?

There are many who disagree that Gregg’s own solo studio album transcended the laid back so far as to more accurately be pronounced DOA. There are others who think that if he ever actually did achieve full consciousness and perhaps even learned to stand erect he would lose all his Pleistocene charisma. (Personally, I have come to the conclusion that he portrays a subhuman so cute that I bet Iggy and Lou and the BOC are all jealous.) In any case, Laid Back was great music to nod out to. (Which is no put down. Just don’t try to listen to it any other time.) But don’t buy the hype — it’s not that slow in Georgia, so Laid Back was a somewhat less than 100% authentic artifact of that exotic tropic clime. As for the live tour album, it stands with Lou Reed’s two live sets as a monument to the efficacy of professional, precise, paycheck-drawing session musicians when it comes to swaddling any moribund musical yestername in enough storebought cosmetic grandeur to make him look like a strutting sharpshooter for at least one more tour.

Gregg’s big solo outing here is “Nevertheless,” a/k/a variations on “Don’t Mess Up a Good Thing.” The band may be having fun and almost cooks, but Gregg sounds like his mind is elsewhere. Where I won’t venture to guess, but I know what’s missing here: tension. The title cut is similarly slack, although it sounds fair and has good lyrics — the whole simply doesn’t do its parts justice. Gregg’s vocal lacks strength, even for the resigned sentiments of the song (the blues as whining capitulation again). Your mind wanders — it’s hellhound on my trail lounge music. The whole group comes off limp, as if some exterior behemoth (Johnny Sandlin?) is holding them up with a giant pair of tongs as they plod on.

For those who make it through the fourteen and a half minute instrumental, the album’s last cut, what will most likely be the final note from the Allman Brothers, is Billy Joe Shaver’s “Sweet Mama,” a piece of sufficient bar band blues music which suggests that if they persevere the Brothers could with a little luck turn into the New Riders of the genre. Of course they’ll break up before that could ever happen, but it’s something to keep in the back of the mind for when their solo careers flop and they all go broke and have to regroup like all the other played out bands who preceded them.

JIMMY CLIFF Follow My Mind (Reprise)

TOOTS AND THE MAYTALS Funky Kingston (Island)

Since he electrified audiences in The Harder They Come, Jimmy Cliff has been his own worst enemy. His songs in that film bristled with passion, energy and conviction; when he wailed, Cliff sounded like the Jamaican Sam Cooke. They were also old songs, though, and by then he had already made his move towards soul and pop reggae, neither of which he performs with comparable commitment. This LP isn’t much different. Considering its message, “The News” has none of the urgency of, say, “Vietnam,” and “Remake the World” comes off a rather desparate stab at duplicating the 1970 chart success of “Wonderful World, Beautiful People.” He does manage to pull off the sentiment of “Dear Mother,” but most often here, reggae’s hypnotic rhythms are muffled, the tracks are globbed up with various superfluous instruments, and Cliff’s vocals are terribly strained. It may be one of his more listenable efforts in the genre, but it’s still very soft-core fare, and hard to get excited about.

Funky Kingston, however, is the hard-core ethnic stuff; as the first Maytals album in America, it is cause for celebration. Toots and the Maytals (Gerry McCarthy and Raleigh Gordon) have been together 13 years without a personnel change, turning out an endless stream of Jamaican hits that whole time. Their main strength is in the songwriting and singing of Toots Hibbert. He can write at the drop of a spliff about seemingly anything, and his songs convey a spirituality that has less to do with Rastafarianism than with the folk wisdom and Christianity of an ancient Delta bluesman.

Toots is the most intense reggae shouter extant. He has a gravelly, gut-wrenching voice that owes a lot to soul music (Otis Redding in particular) . He will sometimes break into scat singing, as if he’d gone into a trance and couldn’t control himself, right in the middle of a line.

Too, Maytals music flaunts influences without ever sounding unoriginal. They weave older Jamaican forms, New Orleans rhythm and blues, gospel, soul, and African chanting into something totally pure and different. Using the same sessionmen as all the other Jamaican singers, the Maytals still coax out of these players much more imaginative, dynamic performances. Funky Kingston is a long overdue album; with the exception of Bob Marley and the Waiters (whose approach to reggae is radically different), Toots and the Maytals have no peers, and it’s about time America got the message.

John Morthland

LINDA RONSTADT Prisoner in Disguise (Asylum)

With Prisoner in Disguise Linda Ronstadt walks the hills in a long black veil, spreading petals of mourning over the countryside . She seems afflicted with a disease diagnosable as Jackson Browne Melancholia, the symptoms being acute, tenderness and bird-fluttering wistfulness... the sorrows of life all met with a sad shrug. Such morose pastoralism has the effect of soaking every song in wine; except for the impossible-to-ruin “Heat Wave,” there isn’t a romping number on the album, and it’s easy to get drunkenly lulled to rest by the damn thing. Moreover, the wounded-by-love sentiments aren’t even expressed intelligently. In the title cut, written by John David Souther, the lyric goes on about how you can’t hide in the city (“everyone knows your number”) and that you can’t be alone even if you try... Bullshit. Whqt crushes someone’s spirit in the city is that they can be intolerably alone — and no one will care. Not even Spider-Man.

Understand: the album isn’t torture, it isn’t like reading the memoirs of Winston Churchill or trying to sit through Merv Griffin’s salute to dairy products. No, it’s just that its pathos is so indifferently expressed; Ronstadt’s voice is the musical equivalent of warm milk, which isn’t my idea of a good time. Prisoner opens with a Neil Young empty called “Love is a Rose,” then slides into “Hey Mister, That’s Me Up on the Jukebox,” a James Taylor sudser. The listener’s metabolism lowers accordingly. But the album gets totally derailed with Smokey Robinson’s “Tracks of My Tears” because when Ronstadt sings “People say I’m the life of the party,” etc., her voice is so leaden with sobriety that? it’s impossible to believe she’s ever been the life of any party.

Which reminds me: what happened to Lesley Gore’s corrife back? She may end up like Eddie Fisher — her comeback will need a comeback.. Her role was such a good one — the woman who says, I’ve been pushed around lpng enough: You don’t own me — that many were anxious for Gore to make another go at it and like Ibsen’s Nora, slam the door one more time. Failing Gore redux, Linda Ronstadt with “You’re No Good” would be a worthy understudy to the role, just as the Dictators could take over if Flo and Eddie ever decided to call it quits. However, the evidence of Prisoner in Disguise is that Ronstadt will only enter from the wings if she is prodded. Gore at least had visceral fire but all of Ronstadt’s effusions seem calculated (and the calculation’s not her own: she seems to do what she’s told) so she seems destined to be a prisoner in disguise all right. And it isn’t love that’s got her locked in...

James Wolcott

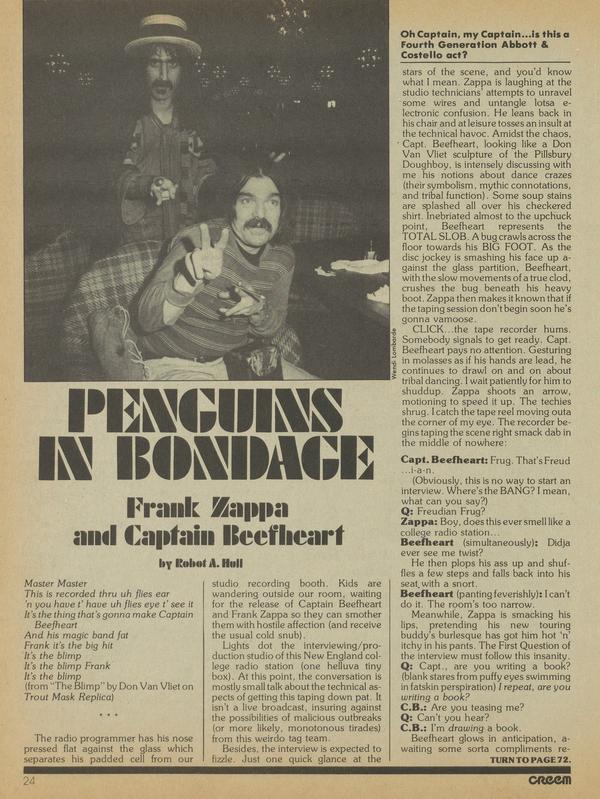

ZAPPA/ BEEF HEART/

MOTHERS Bongo Fury (DiscReet)

A classic Cal Schenkel cover surrounds one of the most listenable Zappa/Mothers records since the old days, but anyone coming to this set to hear Beefheart will be semidisappointed. Semi because he does a lot of singing On Bongo Fury, but what he’s singing are the same old Zappa lyrics, which deal with the same old Zappa hangups. It’s a strange experience to listen to the album’s first cut, “Debra Kadabra,” and hear Beefheart singing like Beefheart, but realize a little way into the song that he’s singing what is essentially a continuation of that ridiculous schtick about the poncho. Beefheart singing about pimples? Shudder.

Zappa’s stuff here features good playing, little talking, and fine singing from his new band. No noise, in other words. But 1 am still tired of his sourness.

But the good Cap gets two recitations, and they so outshine Zappa’s sour bullshit that if I were Zappa I’d have left them off the album. “Sam With the Showing Scalp Flat Top” and “Man With the Woman Head” show that Beefheart still has a lot of good material nobody’s heard. Maybe the next album from this collaboration will reverse itself and have as much Zappa on it as this one has Beefheart. Yeah — more Beefheart and I’ll keep the next album...

EdWard

ABBA

(Atlantic)

Sound waves encircle the globe mesmerizing the populace of countries like France, Greece, Italy, England, etc., international explosive pop, created by Swedes (Abba for short), while over here in America we quietly suffer, enduring synthetic mania from the likes of the Bay City Rollers (ouch!) ABBA IS TAKING THE WHOLE GOD-

DAMN WORLD BY STORM AND WE’RE JUST SITTING AROUND JERKING OFF. Rumors keep sifting over from Europe that Abba has around forty albums in the can, and it’s certainly no lie that strange records by Abba keep popping up in unknown areas of this global pop scene; Listen, teens, it’s right near impossible to keep track of every one of this band’s albums; their course has just not been plotted.

Damn shame, too, considering that every song on this album has hit potential. “SOS” finally crept to semi-hit status, despite a very sloppy promotional campaign. FM stations everywhere dug the spiced, clean, feel of the song and those embryonic interludes on the synthesizer. But “SOS” is surrounded on this elpee by so many good tunes that the mind boggles. Likewise, Abba’s first album (the one with “Waterloo”) in this country was a perfect blend of exceptional, lovable compositions, ranging from bubblegum to psychedelic freakouts (no mean achievement in ’74). This album would stand alone as an immortal brushstroke except that Abba has tried it again (and/ who knows how much more they got up their sleeves?).

Understanding Abba is simple. You gotta squeeze their name. They’re a stuffed-toy band without being cutesy. “Bang-A-Boomerang” bounces, embraces, and then returns just like its name implies. “Rock Me” is like a merry-goround with carnival atmosphere intact. “Mamma Mia” could be the theme song for a teevee sit-com. The catch is to be abstract; versatile and always open to the kiddie market, Abba remains formless as an identity but completely matured in terms of production and professional craft. “Hey, Hey Helen” onthisalbum, for example, is dance music that counters the disco trend by killing em with funk. In contrast, “So Long” splinters into so many directions that its energies crack the world.

Meanwhile, in the midst of all this pop sensationalism, Abba remains cool and collected. Bjorn and Benny are no idiots like Flo and Eddie (a jealous duo), esp. when ya consider the luscious paif of young ladies they’ve attached themselves to. Representing the “A’”s in Abba, these girls sandwich the total sound of the group, sustaining the vocal style on a purifying plateau. Proof that girls (and their voices) were made in Sweden.

SLEEPER OF THE MONTH

GEORGE HARRISON Extra Texture (Apple)

George Harrison expects (craves?) abuse — I mean, he even subtitled this album “Ohnothimagen” so I could probably make him very happy because, with the exception of “You,” this collection is worthless. All the songs sound the same, that is to say. like dirges. And though George has said elsewhere that he wrote “This Guitar (Can’t Keep From Crying)” basically as an excuse to stretch out on guitar (the way Clapton did on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” on the Beatles’ white album), for some reason he doesn’t play a single interesting lick, nor an extended one, instead obliquely railing in the lyrics at the lack of love in this ol’ world, especially amongst the members of the | music press.

But, you know, he’s right; there’s I just no time to hate. So I’m going to love George Harrison and tell him that he should get a producer (not | just to function as engineer either) who can approach his work With I some semblance of objectivity because George is capable of much better stuff, as he proved with his first solo outing and most of his Beatle work from the biting “Don’t Bother Me” on their first album to the inspiring “Here Comes The | Sun” on Abbey Road.

By the way, you may have notice] ed that we did not include a Sleeper | of the Month in the last issue. Well, the new Harrison album more then I covers us for this month and last: Beautyrest ain’t got nothin’ on this I fella!

Robert Duncan

So don’t be fooled. Abba may sound like the Archies, but “Sugar, Sugar” was a catchy song constructed by cartoon mentalities. Abba is putting new life into this “cartoon” pop formula and making some of the happiest music around today.

Robot A. Hull

HARRY CHAPIN “

. Portrait Gallery (Elektra)

The first time I heard Harry Chapin (via “WOLD” on the radio), I couldn’t believe that music of such abysmal naivete could be for real. That labored monotone voice, booming out the idiot chorus “D!D!D!D!” with all the shithead presumption of Jim Nabor$ trying to sing opera — Harry Chapin had to be the new Martin Mull, no less. What a joke!

The joke was on me, of course, as I discovered when I chanced upon a copy of Short Stories a few months later. Not only was “WOLD” for real, it was only one of many such cliche-ridden dirges, all cloaked in the foldout-jacket respectability of ART. Who is this Harry Chapin?, I wondered. An escapee from a sheltered workshop?

With the new Portrait Gallery, I think I’m beginning to get a key to Chapin’s identity and motivations. Like his previous albums, Portrait Gallery is a deluxe, self-indulgent package: flashy if pointless graphics, complete lyrics and credits (even down to the authors of the handclaps), ads for books of Chapin’s “poems,” etc. All of this insistent commodity provides a jarring contrast to the songs themselves, which are almost as embarrassing to read on the jacket as they are to actually listen to. Chapin’s piece de resistance, the 9:57 “Bummer,” a sordid tale of a black kid driven to crime, was already a dated concept when late bloomers Mac Davis and Elvis P. did it as “In the Ghetto” in 1969 — evidently Chapin just recently noticed that it’s tough growing up black, but his lyrics are so shopworn that they approach being racist stereotypes.

Transparent as always, Chapin tips his own psychic.hand with an otherwise humble couplet from his current hit, “Dreams Go By”: “You know I want to be a painter, girl/A real artistic snob.” Yep, Chapin finally hit the nail on the head — I’m afraid that he’s one of those pathetic creatures who lust after art as form rather than expression. How else explain a singer who titles his record albums Short Stories and Portrait Gallery? His media-confusion only shows how desperately he wants to latch on wherever he can as an A-R-T-I-S-T, a word which must burn as brightly as a smile-button night light in the lonely corridors of his mind.

Richard Riegel

“ MOTT

Drive On (Columbia)

Never say die. Muddle through. Smash your head against the wall. It ain’t easy when you fall. You breathe in you breathe out. Take it easy. Take it sleazy; Tpke your pick.

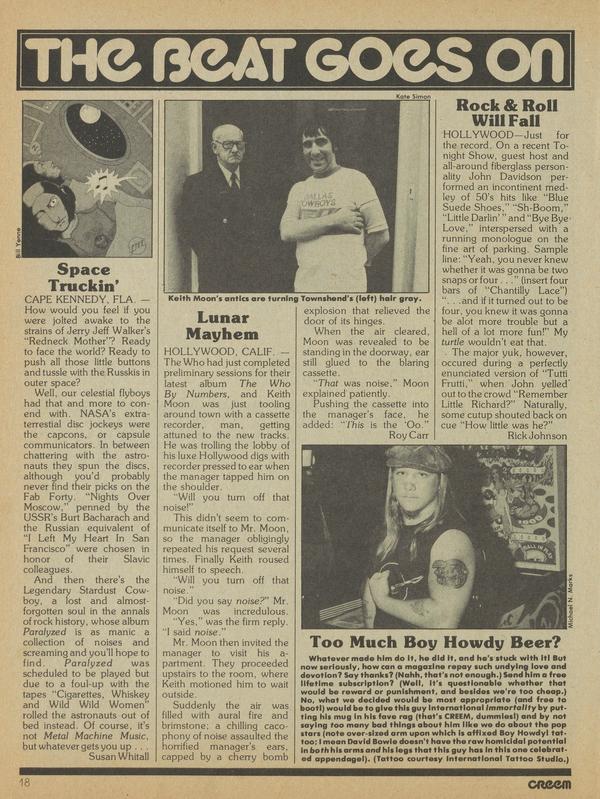

Now it’s Mott with Drive On. The survivors, tied to a mythic legacy, left without the mythmakers, Ian Hunter and the Mick R’s. What’s to do? Pick up some punks by the side of the road and drive on. Obviously.

It’s just the latest chapter in Mott’s regenerative/degenerative process, really. The classic case of a band that never gets it together until the absolute last minute, then blows it after their efforts are rewarded with success.

At the moment, the pendulum’s on the upswing, surprise surprise. Ray Major, the new guitarist, is more power picker than string Bender so he fits in fine. Nigel Benjamin warbles adequate-plus: a little like Hunter, a little like early Paul Rodgers, less distinctive than either.

The tunes are supplied by the two original Mott squatters, proving that droogs ain’t dregs necessarily. Most are Overend’s doing and exhibit the typical rock star, cock star, he-man, me-man prance stance, although he also chips in “Stiff Upper Lip,” a notso-subtle dig at British pop star defections. Buffin’s “It Takes One To Know One” steals the show, though, updating “Summertime Blues” with details of pimps and the P.T.A.

The result of all this lies somewhere between inspired and insipid but in the main, it’s solid, if unexceptional, rock‘n’ roll. Solid enough to keep most of their following happy. Solid enough to keep Columbia happy. Solid enough to make the band happy enough to piss it all away next time out. So be it. Drive on, my sons. Drive until you’re stale.

Michael Davis

GRAC HAN MONCUR III Echoes off Prayer (JCOA)

This album marks the reemerg ence of trombonist Moncur as a prime mover of (the new) music after a decade in the somewhat less moving position of sideman to the heavies—the heavies being such travelers as Jackie McLean and Archie Shepp. Unlike Moncur’s recorded work in the mid-sixties which concentrated on expanding the trombone vocabulary and the compositional possibilities within a small group context (his two masterworks are the Blue Note LPs Evolution and Some Other Stuff, both about due for re-issue, particularly Stuff which has such people as Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and Tony Williams playing intensely responsive spacy-as-in-breathing music like you don’t hear anymore but which was prevalent among the impressionistic second wave of avant-gardists and which seemed to fizzle when everybody started plugging in), Prayer’s main revelation is Moncur as composer/arranger conducting a 17-piece (give or take) orchestra augmented by some voices and the Tanawa Dance Ensemble ’ (who, fortunately, play a variety of percussion instruments as well as hoof). Interesting to note: another trombonist of explorative persuasion, Roswell Rudd, emerged about the same time as Moncur, recorded one extraordinary album as a leader and then submerged to sideman status (again about the same time as Moncur) only to resurface this past year with two excellent albums of his own. A renaissance of the unwieldy bone? Could be. All semblance of objectivity aside, Moncur and Rudd are the only trombonists playing (the new) music who are worth listening to anyway.

Echoes of Prayer is a suite of sorts with sections given black consciousness titles (tho a little wry — “Reverend King’s Wings,” “Medgar’s Menace,” “Garvey’s Ghost,” “Angela’s Angel”), each one a simple repetitive melody/riff with the underlying intricacies of a continual afro-percussion jam. Linking the different sections are a variety of solos ranging from competent to creatively weird, the highlights being a brief duet between bassist Cecil McBee and Charlie Haden and a dancing percussion interlude by the dancing Tanawa Dance Ensemble.

I didn’t like this record when I first heard it — I was expecting the “old” Moncur approach of interwoven im: provisations instead of what is here, which is almost perfectly wedded melody and rhythm with the solos growing organically from the larger body of music. Moncur experimented with this approach as long ago as Evolution (’64) but here his intentions are more accessible, i.e., more successful and ultimately infectious. The record doesn’t grow on you, it grows in you. Great with headphones. Grab the nearest ashtray and ballpoint pen and play along. (I swear that the first section, “Reverend King’s Wings,” is remiof Metal Machine Music but it passes quickly enough and becomes an effective motif. Moncur’s a musician, not a poseur.)

Free listening and ordering information concerning JCOA (Jazz Composers Orchestra Association) records and goodies from other independent labels can be obtained by writing New Music Distribution Service, 6 West 95th Street, New York, N.Y. 10025. You have nothing to lose and they’re waiting to hear from you.

Richard C. Walls

OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN Clearly Love (MCA)

Olivia Newton-John must be for those people who don’t like raucous, overly emotional singers like Karen Carpenter.

She sings pop-country music, but the emotions those songs are about — loneliness, heartache, pain, boredom, the despair of losing someone and not finding anyone else — are completely absent from her performances.

Her backing is absolutely perfect. Her clear, bell-like voice — as pure and impersonal as anything this side of Julie Andrews — is just another part of the wraparound song. This aural module is apparently the work of John Farrar, who is credited with producing and arranging the record, playing electric and acoustic guitar, being a back-up vocalist, and writing one of the songs, “Sail Into Tomorrow.” The song, incidentally, is published by Blue Gum Music, Inc., and one of the other pieces on the LP is called “The Marshmallow Song.” These people don’t care who finds out what they’re up to. I give them credit for their honesty, and if John Farrar isn’t the reason for the hyphen after Newton, he ought to sue.

Arthur Johns gets credit on the album, too. He is listed as Hair Stylist, and he is every bit as good at what he does as John Farrar. There are terrific pictures of Miss NewtonJohn riding a horse wearing denims, lying on a bale of hay in a plaid shirt, smiling with her arms around a colt, and holding a puppy against her red t-shirt. So you see, it is a country album, and Miss Newton-John is not done with a Moog, as I had thought. Her hair looks great in every one of the pictures, and I think her dentist is a genius, too, and should get credit on her next record.

The two most interesting tracks on the record are “Something Better To Do,” which you would think a singer could make you cry with, but which Miss Newton-John sings with a perky cheeriness I associate with Miss America candidates in the talent segment, and “He Ain’t Heavy...Lie’s My Brother.” Neil Diamond recorded “He Ain’t Heavy,” of course, and at least had sense enough to know that it’s a contemporary Mammy song, purveying an OK UNICEF emotion, and he tried to shake the rafters with it, and probably got down on one knee in the studio. Miss Newton-John gets a hair louder on a few phrases, but otherwise doesn’t let the song phase her.

I wonder what kind of sound she would make if she fell off a truck.

Joe Goldberg

BETTY DAVIS Nasty Gal (Island)

Back when I was a boy, things were different. Most records weren’t about fucking. Or if they were — “Stars Fell On Alabama” — they were sly about it. Instead, there were love songs, and, love being a difficult word to rhyme, aspirations were limited. You wanted to fit with someone hand in gjove, or at that person’s touch, your heart soared like a dove. Well, now the lid is off— Love Unlimited, indeed — and you don’t reach for someone like stars above, you want to be inside of them or have them inside you. Time was when walking beside was the best you could hope for. But no more. You don’t need a Puff the Magic Dragon Decoder Ring to unscramble these lyrics, as you did when Vice President Agnew was trying to keep dope off the airwaves. And with this whole new market uncovered, it should surprise no one that people are staking out claims to specific parts of the territory, as happened when the movies discovered sex a few years back.

Betty Davis seems to be going for the Sadie-Maisie disco trade. She doesn’t think you are man enough to buy her record. Her voice is harsh and scraping, but it doesn’t have to be, because on a song she wrote with her former husband Miles Davis, she sings as sweet as you please. (That song, “You and Me,” arranged by Gil Evans and almost surely with Miles on trumpet — it’s all who you know in this business — is gentle and perceptive, and quite unlike anything else on the record.)

Everything is done over an expert, insistent disco beat, and each one ends so abruptly that 1 can imagine why Ms. Davis is so pissed off. The lyrics, which are printed on the inside sleeve in capital letters, and are published by Higher Music Publishing Inc./Mabry Music Co. (ASCAP), seem to have been transscribed from performances, because every, stray OH BABY is reproduced. Here are some of them:

1 HURT YOU BAD AND 1 CAUSE YOU PAIN YEA

YOU SAID I WASN’T NOTHIN BUT A DIRTY DOG

BUT YOU STILL WANT ME BACK AGAIN BACK AGAIN

THEY SAY YOU LOVE TO LOVE IN THE SADDLE

WELL WHEN I’M THROUGH WITH YOU

YOUR RIDIN DAYS WILL BE OVER

There is a song here called “Dedicated to the Press,” which is about how she has been called vulgar, but can only be what she is, and why don’t people like and understand her, and she doesn’t care anyway. Which is all well and good, but while I got this album for free, you won’t.

The album cover is pure Carly Simon, but inside, it’s Yoko Ono all the way.

Joe Goldberg

MONTROSE Warner Bros. Presents Montrose (Warner Bros.)

In two previous pythonic displays of rampaging Robitussin-inflamed teenage sweat, Ronnie Montrose has established himself as the pontifex of the daycare center for the children of the grave. During the course of these rapacious odes to rock ‘n’ roll Walpurgisnacht, he laid down a viscid set of fiercely blocked power chords tethered by a technocratic sensuousness, whose shamelessness went beyond the mere definition of “heavy metal” music and on into the realms of vitreousness. However, on this foray into sonicology, he doesn’t quite grab the crystal with as much gusto as he did before, even though he does manage to sustain a certain level of gritty dissonance expected of all tertiary katzenjammers; which simply means the album gets a B on the old Ripple-o-meter!!!

Dancing outa his rock abattoir, Ronnie runs roughshod through the void with a Deep Purple intoned piece of purulence laconically tagged “The Matriarch.” Emblematic of all cosmic indolence and frenetic lyrical imagism, this song spills over the edge of the world into the heebee-jeebie hallucinatory world of Jim Starlin’s “Warlock” Marvelbooks. Creeping along close behind is a necropolis mass transit commercial “Black Trajn” whose underlying deathblow guitar larceny is highly reminiscent of Savoy Brown’s “Hellhound Train” and Black Sabbath’s classic, hymn to uselessness, “Into the Void.” The two nostalgia nuggets on the disc are the Eddie Cochran popularized “Twenty Flight Rock,” in which Ronnie’s less complicated roots are shown to best advantage, and “Dancin’ Feet” with its swirling guitar and infectious “For men only” backbeats. Overall this record satisfies, yet never really attains the promise of herpetophilia (a.k.a. snake-sex — Ed.) found on the first Montrose LP and Paper Money.

Joe Fernbacher (Thanks Joe. The first reader who can interpret and define every word in this review for us wins 'a free copy of the American released reggae album of his or her choice. — Ed.)

THETONY BENNETT/ BILL EVANS ALBUM (Fantasy)

Youth of America, we’ve been deceived. Betrayed. Swindled. Hoodwinked.

Because The Tony Bennett/Bill Evans Album is incontrovertible proof that the greatest make-out music is not rock or soul (roll over Barry White — if you can) or braindamage boogie; it’s saloon music. Think of it: just a singer and piano, smoke in the air, wine in the glass, and a willowy woman leaning on your shoulder saying, “But, daddy, I’ve got to go to work tomorrow...” Much more concupiscent an experience than being at a Z Z Top concert trying to cop a feel while some denimed drunk-out uses your seating section as an impromptu vomitorium.

So reconsider, Young Americans. “Bennett/Evans” (Tony Bennett: vocals, Bill Evans: piano) is intimate, suggestive, becalmed, with Bennett’s voice soothing every molecule in your battered and beleaguered metabolism. And songs like “My Foolish Heart,” “Days of Wine and Roses,” and “When in Rome” are cuddle-up classics. You simply can’t go wrong: this album is the essence of kissiness.

James Wolcott

FIRESIGN THEATRE In The Next World, You’re On Your Own (Columbia)

PROCTER & BERGMAN What This Country Needs (Columbia)

This is no place to start.

The Firesign Theatre has developed during their past 5 or 6 albums a repertoire of sounds, words, and characters. The sounds

are a result of exploring the possibilities of space age recording studio technology tho apparently the favorite sounds employed by the FT (favorite of both FT and fans) are satirical reproductions of the sound “effects” used on radio 30 years ago and more. Sounds not as funny as you thought when, you were in the zone and not as innovative either. The words, which is where their mastery lies, form reoccurring non sequiturs (people are often places and vice versa, nouns become verbs, stuff like that), incomplete references, i.e., using characters and characterizations (voice patterns they do special) as well as phrases (“more sugar,” “trail of tears”) from past albums which originally occured in a context with meaning but just as often did not which is all very disorienting unless you’re familiar with the FT canon. The final aspect of their wordplay, which is very predominant and frequently irritating (particularly on the P&B album), is the god help us lowly pun. Their puns are puns like all puns and some of them are pretty awful and some of them are interesting because of their relationship to the FT oeuvre as delineated above but very few of them are funny unless you’re so unraveled by your favorite drug that you can’t tell a dog biscuit from the real thing and frankly folks that’s the only way to listen to these albums. I know. And that’s the unfortunate

irony of the FT albums -that even tho the richness of their presentations (speedy jokes, oblique references that take awhile to figure out) eliminates the major problem of comedy albums which is that they can’t maintain their surprises (the source of humor, you see) for more than two listenings, tops, the fact remains that if you sit down straight arrow sane and/or sober then you’re not going to find the Firesign Theatre terribly funny. And this album’s no exception.

O.K., that’s enough info for the non-Firesign buffs...now for all you bozos who know all the passwords here’s the straight poop on this latest effort. It’s as good, maybe better than their last one (tho not as good as Dwarf or spooky as Bozos) mainly because the focus here is “tell a vision” with lotsa police stuff, soap operas, quiz shows, commercials... even a plot or two (one which is foiled) as well as a guest appearance by George Leroy Tirebiter at the Academy Awards.

All the material on the FT album is by the Austin, Ossman half of the quartet (but performed by all 4), presumably written while fellow players Procter and Bergman were getting their post-psychedelic Abbott and Costello act together which is captured live at N.Y.’s famed Bottom Line on the What This Country Needs album (subtitled “A Good 5 Cent Joke,” something they have trouble coming up with). It’s a problem album, a series of sketches interrupted by annoying applause that has the hit then miss quality of hip vaudeville but it also has a ton of goddam puns and simple minded jokes (tho one bit, entitled “Callbak,” is a satire on radio telephone talk shows and a gem). These guys need a studio where they can camouflage the simple stuff and develop the sounds. They’re probably great in person but recorded they’re just another record, albeit stranger than most.

But this is no place to start. If you’re not a Firesign fan (through negligence...those who have tasted and spit never come back) then you should buy their first album Waiting For The Electrician Or Someone like Him, immerse yourself and then buy each album in sequence (they’re still available) until you can’t stand it anymore, which might be immediately, or until you find yourself enamored of the funniest comedy team (especially if you take lotsa drugs) in existence as of now (Oct. 28, ’75). Otherwise, it’s like (and I can’t resist this) picking up John Coltrane’s record Om, listening to it and deciding that he’s a ruse without checking out the 15 years of recorded development that led up to it. It really is.

And if you ate a Firesign fan then you already know what to do.

Richard C. Walls

DARYL HALL & JOHN OATES (RCA)

These boys have been trying hard, and soon they may even make it. Certainly this, their first good album, shows that they have it in them.

Their metamorphosis has been interesting: starting out as “Whole Oats” with your typical laid-back singer/song writer number, and going on to become Meaningful Songwriters, thence to having an entire album (War Babies, with a cover touching all the bases: nostalgia for the 50’s, political statement, and the development of the Artist) produced by mutant vegetable king Todd (fellow Philly rocker at that), and now to a new label and a new look, sort of faglitter/sci-fi.

Inside (ignoring the nude poster) is a good, soul-inflected record featuring some really fine tunes (notably “Sara Smile,” “Alone Too Long” and the amusing music-biz inside-joke “Gino (the Manager)”) that aren’t helped by indifferent sessionmen but shine nonetheless. The only total failure is the wretched attempt at this year’s big reggae hit, “Soldering,” which those same session-men naturally cannot play at all.

Hall and Oates make successful white soul kids. With a tad bit more attention to production and perhaps a couple more uptempo tunes, they could have some hits.

EdWard

MANFRED MANN’S EARTHBAND Nightingales and Bombers (Chrysalis)'

Here’s proof that Bruce Springsteen is “the new Dylan”: Manfred

Mann has covered one of his songs. Now Manfred’s constructed a subplot to a career recording Dylan songs, going back at least as early as “The Mighty Quinn.” On Nightingales and Bombers, Mann includes the statutory Dylan reading, the obscure “Quit Your Low Down Ways,” but it is Springsteen’s “Spirit in the Night” — rendered, unfortunately, rather ELO-ishly — that will attract attention. Ironically, Bruce returns the favor. When we saw him live, he did “Pretty Flamingo” and “Sha La La.” The last time we saw Dylan, he did not sing “Doo Wah Diddy.”

From such secondary pop gems, Manfred Mann and the Earth Band (after a brief passage through pop jazz) went synthesizer. The last album, The Good Earth was an almost total disaster, on which they approached the nadir of Dylanization by spending ten minutes neutering the already neut “Father of Night.” Nightingales and Bombers is a substantial improvement, full of minor rewards.

Manfred Mann with a synthesizer is kind of like a non-infantile Todd Rundgren. Fortunately, Manfred and the hard driving Earth Band don’t regard melody and taste as non-Utopian concepts. Rather than referring to either Todd (excessive) or the Krauts (soporific), Mann’s synthesizing is more in line with Townshend on Who’s Next. Songs come first; besides Springsteen and Dylan, there’s “Visionary Mountains,” a lilting song by folksinger Joan Armatrading, and a number of Earth Band originals, most of them full of motion and vitality. On “As

Above, So Below” we’re treated to the sound of nightingales singing while bombers fly overhead: recorded live during World War II by a British ornithologist. I don’t know if that’ll make your day, but it sure made mine. Wayne Robins

BILLY SWAN Rock ‘n’ Roll Moon (Monument)

Billy Swan is one of those strange Seventies mutations, a product of a time when musical boundaries are breaking down at an accelerating rate. He doesn’t really belong in any category, by more traditional standards, but he does well in nearly all of them: rock, easy listening, and country.

, He’s got country twang and voice, enough beat and guitar flash to qualify as rock, and the kind of melodies that go well on the MOR stations. In covering all the bases, he makes pleasant music that sounds better in the background than foreground.

For example, “Everything’s the Same (Ain’t Nothin’ Changed).” Instant hit, everywhere, just like “I Can Help.” Once you’ve heard the damn thing, you can’t shake it. Billy’s chipper, devil-may-care vocals and melody, along with the rolling rhythms, nearly even cover up the bitterness and utter contempt that are at the heart of the song. The analogue to last album’s “Don’t Be Cruel” is his slowed-down version of Johnny Cash’s “Home of the Blues.” The rest is pretty much the same — perky melodies, clever word plays, a loose feeling — with one exception. Swan does a sterling version of “Ubangi Stomp',” a rockabilly classic that polite, progressive white Southerners have refrained from performing for a good 10 years because of its rather blatant racial innuendos.

Swan can be by turns tuneful, soulful, funky, precise, tough, and comforting. His records meet all criteria for satisfying music except one: close, sustained listening. It all depends on what you want out of music. John Morthland

AMON DUUL II Made In Germany (Atco)

No one but this X-th generation German-American seems to have remarked on the profound ironies of Kraftwerk’s recent boast that they’re the first German pop group to actually sing in German. Der Fuhrer’s ashes must be doing cartwheels in some Berlin garbage can, to know that his blond-haired, blueeyed kinder have been singing their hearts out in the “Negroid doggerel” of the American language thus far in the history of pop.

While Chuck Berry-ized English is of course the Esperanto of rock ‘n’ roll, young Germans are doubly cautious of ethnic assertiveness, for, as every good citizen of the Bundesrepublik knows, celebrations of German racial pride during modern history have too often escalated into set - the - controls - for - the - heart -of - Hades apocalypses.

Amon Duul II are still singing in English, even to the point of sarcastically affecting that old Hogan’s Heroes’ chestnut, “Krauts,” to describe their own kind, but in Made in Germany, they are also finally dealing with unmistakably German subject matter. The promulgation of instrumental “space rock” by so many German groups has been a symptom not only of their fascination with applied technology, but also of their reluctance to lyricize the questions of their own identity; synthesizers have no racial skeletons in the closet.

Made in Germany is being billed as a “rock opera,” but with the whole of modern German history as its massive subject, the album is less a unified opera than a -series of precisely - instru mented, flawlesslynarrated vignettes suggesting several highlights of that history, as seen by AD II. “Metropolis” is the expected reworking of the cabaretas-decadence metaphor for preNazi Berlin, “Dreams” is an oddly sentimental depiction of the HitlerEva Braun relationship, and “Loosey Girls” portrays the general dislocations of West German society after World War II. “5.5.55” is the best rocker on Mode in Germany, a silver Porsche 911 of a tune designed for ausgekicken die Jamzen; the subject is the “economic miracle” of postwar Germany, a phenomenon treated with grudging respect by the old communedwellers of Amon Duul II. (Ja, they probably all drive VWs, too.)

“Mr. Kraut’s Jinx,” the ostensible cosmic truth of the set, a meandering saga about a tragically-flawed German rock group (Lucifer’s Friend?) out to conquer the world, concludes dramatically with the watchword, “Future ain’t tomorrow, future is today!” Since Hitler also lived by that motto when he was overrunning Europe, Fm not sure what moral precept AD II hopes to impart to us, but the cut is priceless nonetheless for Chris Karrer’s luxuriously guttural pronunciation of “extraterrestrial.”

As a compulsive student of the cultural history of Der Vaterland, I’m looking forward to further song cycles defining all the quirks of the German soul; for now, Made in Germany is an ambitious beginning at that task. Richard Riegel

FLASH CADILLAC Sons of the Beaches (Private Stock)

What lame-o group is finally going to win the distinction of recording The Last “Fifties” Song of the Seventies? Just when 1 thought the sub-genre had run out of grease, here comes Chicago with that one about blue jeans, comic books and movies, and now Loggins & Messina have undertaken their Oldies Songbook. When’s it going to end?

One group that hasn’t had time to bother answering the question is Flash Cadillac. Originally first-rate purveyors of “Fifties music,” they’ve moved fast enough through rock’s back pages to have already turned in the definitive surfing/hot rod album of the decade. Sons of the Beaches is probably the best Beach Boys record of the last five years, it’s as strong and as spotty, say, as Summer Da^s or Surfer Girl, and if Brian Wilson was a genius for pulling off “Don’t Worry Baby,” then Kris Moe and his bunch are at least Rhodes scholars nominees for delivering goods like “Time Will Tell” and “It’s A Summer Night.” Easily Flash Cad’s finest forty minutes, Sons is one of the most likeable albums of 1975, a sheer delight. But it raises a few unsettling questions about the group’s future.

For instance, will their, audience move fast enough to keep up with F. Cad? Will those who bopped and strolled to No Face Like Chrome and swam off the deep end to Sons of the Beaches be ready for 1977’s Compass of My Mind and its mindbending 22-minute sitar opus; “Mind Aflame”? Will they even bother to tune in in ’79 when Flash celebrates the tenth anniversary pf heavy metal with I-Beams — Anguish, in 1980 when the band loses itself to hard drugs and Harleys and Kris Moe exits solo to record the reflective What’s Wrong With This Universe?

Uncomfortable as they may be, these are the questions the band must begin asking itself now. A little parody goes a long way and affectionate satire can be an enticing game to get into, but a topnotch writing/recording/performing outfit with a sense of humor is a rare commodity. Know this, Cad: you got it all. Don’t lose it.

Gene Sculatti

LOGGINS & MESSINA So Fine (Columbia)

Something happened to Loggins and Messina. They recorded three thoroughly catchy pop-country albums that included a few AM hits and some FM sleepers (my favorite: “Rock ‘n’ Roll Mood” on the first LP) and at least in rock’s ever-expanding Tin Pan Alley the sky seemed the limit for this duo. So last year they released the obligatory live set, and why shouldn’t they take that rest? But nearly a year later — that works out to about two years of rest, fellas — they’ve put out an album of country, r&b, and rock oldies that is so casual, so uninspired, so... sleepy that one can only speculate that they forgot to set their alarm clocks two. years back.

If you can imagine the wild, screechy, squealy Bobby Darin of old taking his infamous “Splish Splash” bath in...no. make that under molasses you have some idea of what this collection sounds like. I’ve noticed that they’ve chosen to release “A Lover’s Question” as the single; while it’s unquestionably the best cut here, it, too, barely rises above the soporific, so please don’t let it fool you into buying the album. So Fine is just so bad. Though I rarely recommend that people go back and buy the originals if a set of covers is decent, none of these versions comes close to doing these songs justice.

Either L & M’s muse has packed up and left them desperate for material or this is an attempt at a rip-off or a fairly successful career has lulled Loggins and Messina into thinking that their favorite jam numbers are solid salable product. I could be wrong on some counts, but with this album, be it cynical or sincere, this once-promising pair is dead wrong.

Robert Duncan

CANNONBALL ADDERLEY Big Man (Fantasy)

Cannonball Adderley, who died earlier this year of a stroke at the age of forty-nine, was an excellent musician, a skillful popularizer, and as good an ambassador as jazz has ever had. Articulate and amusing, he was aware that jazz is part of show business, and, unlike many of his contemporaries, seemed to enjoy that it is. A former high-school teacher, he always met his audiences more than half-way, telling them what he was going to do, and they loved him for it. He was so good at that part of his act that he even had a talk show on Los Angeles television for a while.

He played alto sax, perhaps most notably in a middle-Fifties Miles Davis group that also included John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones, and with his own group, which he formed with his brother Nat, he had a fine string of funky hits, the most popular of which was Dis Here. Maybe the best record he ever made was a Blue Note LP called Somethin’ Else, on which Miles Davis was his sideman.

This LP, which is a two-record set based on the legend of John Henry, was apparently of great importance to him, and he had big hopes for it. I wish I liked it more. The idea seems to have been to create a folk musical, an updated work like Lonesome Train or Ballad for Americans, but for some reason, projects like this have gotten bogged down in banality from Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha to Dave Brubeck’sThe Real Ambassadors.

The project seems to have begun as the idea of Broadway producer George W. George and the creator of ABC’s latest soap opera Ryan’s Hope, and that may be the trouble right there. The John Henry legend has always been involved in blackness and man vs; machine, but this version adds John Henry as a taleteller claiming to be De Lawd’s right hand man, in a manner right out of Roark Bradford’s Ole Man Adam and His Chillun. Most of the lyrics are folksy in the style of Oscar Hammerstein II, and, while the casting of Las Vegas bluesman Joe Williams as John Henry might have seemed inevitable, he is still, as far as I can see, just doing his Jolly Black Giant number.

The chorus could have been better recorded, and the one number likely to last is “Gonna Give Lovin’ A Try,” sung by Randy Crawford.

I’m sure Cannonball did this, as he did everything, with the best intentions in the world, but I doubt it’s what he’ll be remembered for.

Joe Goldberg

RUBYSTARR ANDGREYGHOST (Capitol)

The Janis Joplin influences are a little blatant, but it’s the strange idiosyncratic quality of Ruby Starr’s voice which makes you listen through at least once. As soon as the perverse fascination leaves (the same one with which you listen to Jim Dandy , and BOA’s managerial gent Butch Stone is also involved with Ruby Starr.), it’s up to the tunes. And I like ’em.

They deal with hard drinking, hard living, all the rough-ridin cliches, like Suzi Quatro Of The Ozarks. But they’re played well by a band which seems to be shunted into the background like Full Tilt Boogie was (and no “Buried Alive In The Blues” to rescue credibility, either), and Starr’s inflection and phrasing are strangely easy on the ears. The band contributes mainly rhythm and some ho-hum fills, belts out ballsy harmony and leaves the rest to Miz Starr.

She has a strange — maybe affected? — accent which adds interest, but it’s mainly the strained vocal quality and fascinating presence which keeps this record on my changer. On “Witching Hour,” she sounds like she’s been speeded up 33 1/3 revolutions; some ingratiating pronunciations pepper my favorite cut, “Did It Again,” and “Sweet, Sweet, Sweet,” a formula rural boogie piece. They’re not bad.

The compositions even have more than might be expected. There are some beautiful changes in the opener, “Burnin’ Whiskey,” and interesting rhythmic constructions throughout. It’s a sleeper if ever I saw one: the kind of record that gets under'your skin slowly but surely. Buy it, keep it on the stack, forget about it. You’ll be reaching for it, because it’ll be the only record you own which hits certain color; when you’re hungry for this type of music, only this record will do.

Tom Dupree